THE RISE OF NAPOLEON

How the French Republic was seduced by its charismatic and calculating war-hero

Written by William Doyle

EXPERT BIO

PROFESSOR WILLIAM DOYLE

Professor William Doyle is senior research fellow in Historical Studies and emeritus professor of History at the University of Bristol. He specialises in 18th-century France with several books exploring the causes, events and consequences of the French Revolution.

“Is

he lucky?” Napoleon

would often ask when appointing a new general. He knew from his own life and career what that meant. He believed there was a lucky star guiding his destiny, and it shone on him from the moment of his birth. If he had been born two years earlier, he would have been Genoese, not French, since his native Corsica was only ceded to France in 1768. And he was lucky to be born a nobleman, because this status qualified him for admission into officer training schools in mainland France.

Yet he knew that however well he did, he could never hope to rise high in the royal army, since the most prestigious ranks were reserved for courtiers. In any case, mocked for his remote origins and Italian name and accent, he was not a happy cadet. He had plenty of ambition, but his youthful dream was to return to Corsica and lead a movement to liberate the island from French rule. He spent much of his first years as a commissioned officer back home on leave, seeking glorious native opportunities. But it was the French Revolution that provided them, on a much grander scale.

REVOLUTIONARY OPPORTUNITIES

Though not a political activist in 1789, Napoleon was sympathetic to the reformist aims of the Revolution, and at first he welcomed the return from exile of the former leader of Corsican resistance to French annexation, Pasquale Paoli. But Paoli was soon at loggerheads with the revolutionary regime that had initially allowed him back, and he was suspicious of the extensive and influential Bonaparte family. Months of increasingly bitter rivalry culminated in June 1793 in the whole clan being hounded out of the island. They took refuge in France, and from now on Napoleon abandoned his Corsican ambitions and committed himself wholeheartedly to the service of the revolutionary republic.

Luck once more favoured him. He was still a commissioned officer, but the officer corps as a whole had been decimated by the emigration of thousands of noblemen when the revolutionaries quarrelled with the king, and then overthrew the monarchy. There were thus unexpected opportunities for officers who remained with the colours, especially since the new republic was soon at war with much of Europe. As yet Napoleon had almost no combat experience, and had been horrified by his first sight of dead bodies as he watched from the sidelines when the royal palace was stormed on 10 August 1792. But, trained in artillery, he proved a useful recruit at the Siege of Toulon, the naval port occupied since August 1793 by counter-revolutionaries and the British.

Pasquale Paoli, a Corsican compatriot of Bonaparte and leader of its resistance movement

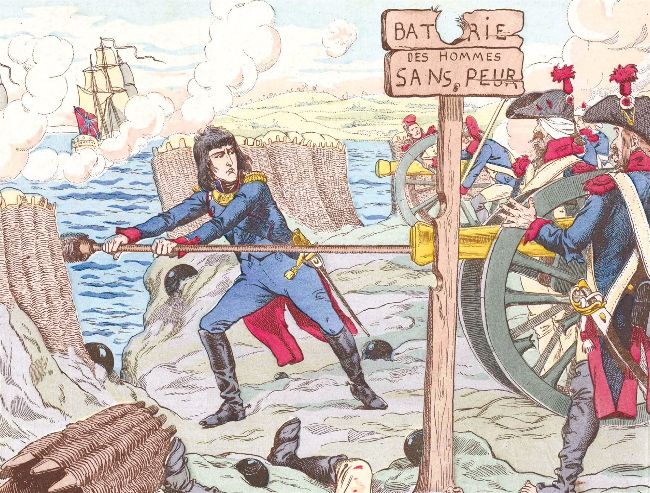

Napoleon was in charge of the artillery at the Siege of Toulon in 1793

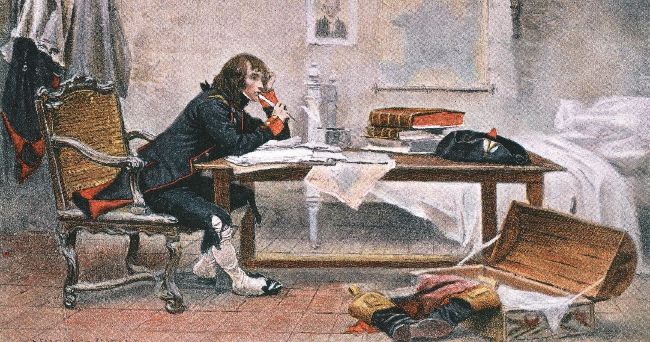

From 1779 to 1784, Bonaparte was enrolled in the Military School in Brienne, Champagne

The Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789 was a key moment for the Revolution

All images: © Alamy, © Getty Images

“THOUGH NOT A POLITICAL ACTIVIST IN 1789, HE WAS SYMPATHETIC TO THE REFORMIST AIMS OF THE REVOLUTION”

There he received his first combat wound, but devised a plan of bombardment that would drive the enemy out of the port. Its success brought him the sort of meteoric promotion that only occurs in wartime, from captain to one-star general.