Breathless

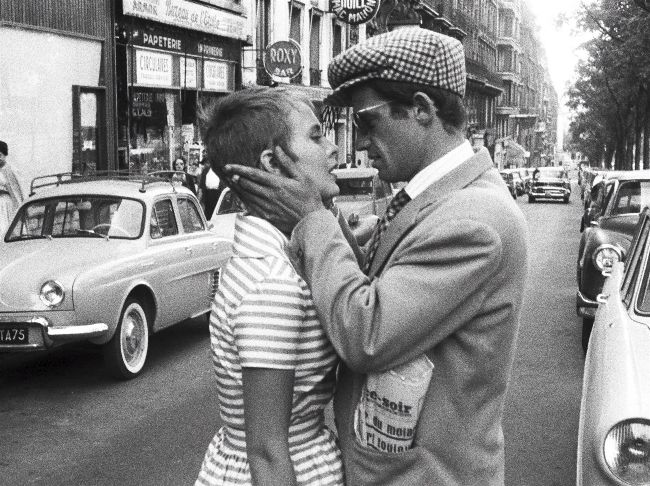

Jean Seberg — cementing the striped top as the epitome of French sartorial style — and Jean-Paul Belmondo, icons of the French New Wave.

THE MASTERPTECE

we reassess the greatest films of all time , one film at a time

ON 16 MARCH 1960, premiering on just four screens, Breathless changed cinema forever. Jean-Luc Godard’s debut feature — À Bout De Souffle in its native tongue — transformed the past, present and future of movies in just 90 minutes, playing fast and loose with classical cinema, loosening up its strictures to become something startling and new, a constant well for filmmakers to draw from that still feels refreshing today. Tonally, it’s a curio. It fizzes by on the joy of cinematic possibility but is tempered by an undertow of melancholy, a revelry in nihilism. It ODs on adolescent urgency, cinema as punk rock but with far more sophistication and better haircuts. It’s frankly as exciting and essential as movies get. To borrow a social-media standard, yeah, sex is great and everything, but have you ever felt the full force of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless?

Based on an idea cooked up by Godard’s Cahiers du Cinéma compadre François Truffaut, Breathless is the ultimate expression of the Godardian maxim, “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.” Car thief Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) kills a cop and heads to Paris to evade capture by hanging with his American girlfriend Patricia (Jean Seberg). Michel is a wannabe Bogart, a Boyard cigarette (Godard’s preferred brand) perma-hanging from his lips, insouciantly breaking the fourth wall on a car drive, constantly pulling faces in the mirror as if taking a selfie without a phone. Then aged 26, Belmondo provides a model for the superficially tough but actually sensitive anti-heroes later played by everyone from Pacino and Nicholson to Penn and Driver. Yet Seberg’s Patricia, sporting a now iconic combo of pixie haircut and a New York Herald Tribune tee, is arguably the more interesting presence, morally ambiguous, potentially more dangerous, so much more than a catalyst for the hero’s actions. There is a 26-minute bedroom sequence in which the couple flirt, drop literary quotes (“Between grief and nothing, I will take grief,” Patricia says, borrowing William Faulkner) and make out. It’s spontaneous, vibrant and catnip to low-budget filmmakers. If you’ve ever sat through an American indie in which the characters smoke and endlessly navel-gaze, Breathless is to blame.