Need to Know

1 SCENE OF WAR

Across the world, the stage was set for battle – and Britain was in the limelight

330,000

The number of British and French troops successfully evacuated from Dunkirk

Within a few hours of each other, on 3 September 1939, Britain and France declared war against Nazi Germany following its invasion of Poland. With the exception of a brief French incursion into Germany, a few notable naval actions and some small-scale bombing raids, the opening months of the conflict were remarkably quiet. As such, the period gained the nickname ‘the Phoney War’. In the spring of 1940, all that changed.

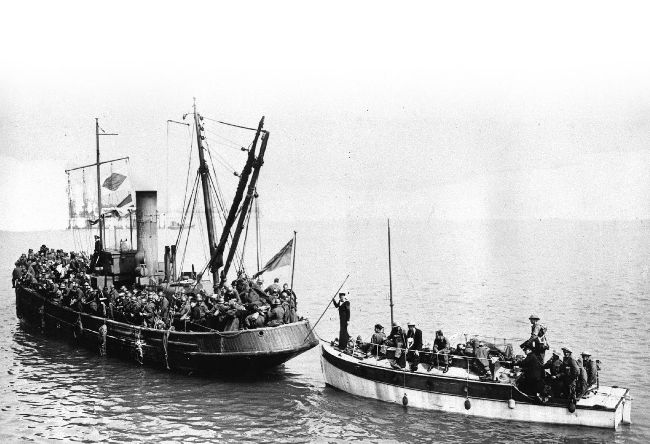

RESCUE RAFTS Churchill pledged that the dramatic rescue of stranded Allied troops from Dunkirk would not signal defeat

GETTY X6, PRESS ASSOCIATION X2, MARY EVANS X1

DINKY BOATS

A flotilla of little ships was mustered to support the Royal Navy in its rescue of Allied troops from Dunkirk.

In April, the Germans began their conquest of Norway and then, on 10 May, they invaded France and Belgium. Bypassing the heavily fortified Maginot Line, which ran along the Franco-German border, and employing fast-moving Blitzkrieg (‘lightning war’) tactics they swept through the Ardennes before turning for the coast, cutting off hundreds of thousands of French and British soldiers at Dunkirk. Operation Dynamo, the Allied evacuation from those beaches, brought over 300,000 of them back to England. But France had been knocked out of the war, and the British had been forced to leave most of their equipment behind. Hitler expected the British to come to terms but Winston Churchill – the new British Prime Minister – was having none of it. Scorning surrender, he demonstrated to the world (and to the US in particular) Britain’s ruthless determination to fight on by attacking the fleet of its former ally, France, to prevent it from falling into German hands. Faced with what he saw as stubborn intransigence on the part of Britain, Hitler planned to force its surrender by bombing, naval blockade or, as a last resort, invasion. But to do this he needed to gain mastery of the skies over Britain, which meant knocking out the Royal Air Force (RAF). Only then could a large-enough bombing campaign be mounted to force the British to the negotiating table, or an invasion force have any chance of crossing the English Channel in the face of the powerful Royal Navy.

But the RAF was a tough nut to crack. It may have been outnumbered, but it had some highly effective fighter planes, the industrial means to replace them and an excellent command and control system. The Germans mounted raid after raid that summer but, by mid-September, the RAF was as effective as ever and the German invasion plans were permanently shelved.

Britain’s decision to fight on, and the ability of the Royal Navy and the RAF to back up that decision, was to have huge consequences. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Britain was able to send arms and supplies to its new ally. And when the US entered the war in December, Britain became a base from which the fight could be taken to Germany, firstly through the bomber offensive and, later, as the springboard for the invasion and liberation of western Europe.

THE MEN AT THE TOP KEY PLAYERS

AIR CHIEF MARSHAL SIR HUGH DOWDING

The Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, Dowding modernised Britain’s aerial defences, encouraged the design of modern fighter planes and supported the development of radar.

REICHSMARSCHALL HERMANN GÖRING

A WWI flying ace who took over the fighter wing once led by the ‘Red Baron’, Göring was Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe during the Battle. In 1946, he committed suicide before he was due to be executed for war crimes.

AIR VICE-MARSHAL KEITH PARK

A flying ace in WWI, New Zealand-born Park commanded the Number 11 Fighter Group – responsible for the defence of London and the South East, and bore the brunt of the fighting.