Podman

MANAGE YOUR APPS!

David Rutland looks at dependency hell and the benefits of containers, and gets to grips with Podman, the newest container tool.

The concept of open source is a wonderful thing – and without it, the technological landscape in which we exist would be fundamentally different, and probably worse.

Not least because your favourite computer mag would have no reason to exist.

Its greatest feature is that if you’re building a software project, you don’t need to start completely from scratch. You don’t need to build your own stack from the ground up, and you don’t need to pay licensing fees for existing components and pass that cost on to your eventual users.

If you’re developing an app, for instance, you can say that it has dependencies – other pieces of open source software it needs to run. When the user installs your fancy toy on their home machine, they already have some of these dependencies present, and their package manager fetches the rest from the default repositories.

In many cases, this isn’t a problem. A single typed command and a password confirmation sees the fruits of your labour deployed successfully on tens of thousands of machines across the globe. Happiness and GitHub stars all round.

In real life, it doesn’t always work like that. Software is constantly being updated, and the dependencies on which your awesomely useful program relies change in functionality. Features are deprecated, and the way in which you interact with other features shifts. Read on to find out what you can do about it…

CREDIT: Magictorch

Dodging dependency hell

Containerisation can stop you drifting through these levels of hell.

Take Python – it’s one of the most popular programming languages in the world, and has T been used for millions of individual coding projects. The current version is 3.11, and while it comes with various upgrades for speed and security, it deprecates several features, functions and modules. If a Python app you wrote a few years ago uses binhex, distutils or gettext functions, it won’t run on the most up-to-date installs. While readers of Linux Format probably wouldn’t have too much of a problem specifying which Python version to use, it makes the experience more difficult than it needs to be. If you’re a developer, it means you either need to regularly go back and update your code so the app works with a broader variety of software setups, or abandon it and hope that somebody finds it useful enough to fork.

Python is an obvious example, but individual libraries can be a problem, too. If you’ve ever deployed software more than five years older than your distro release date, you’ll have run into dependency hell. Libraries and dependencies are obsolete, and you often find yourself in a labyrinth comprising dead ends, broken links, absent archives, forgotten files and, eventually, rage. In the event that you eventually find the exact version of glibstreamer you need, installing it may destroy the functionality of other apps on your system.

Historically, one way of ensuring that software will work on your system is to deploy it in a virtual machine of appropriate vintage, then create a virtual disk image (VDI). You can tote your VDI from system to system through the years, and always have a working copy of Literature & Latte’s excellent, but long abandoned, 2011 Scrivener beta for Linux.

But VMs are huge and cumbersome, and it’s ludicrous to have an entire virtual distro just to run one app.

Keep it contained

Containerisation is a different way of deploying software. It doesn’t rely on packages and dependencies you already have on your system or may need to install. Nor does it require you to spin up entire consumer-grade distros for each app you plan to use.

With Podman search, you can search for container images across as many registries as you like. Not all images are relevant.

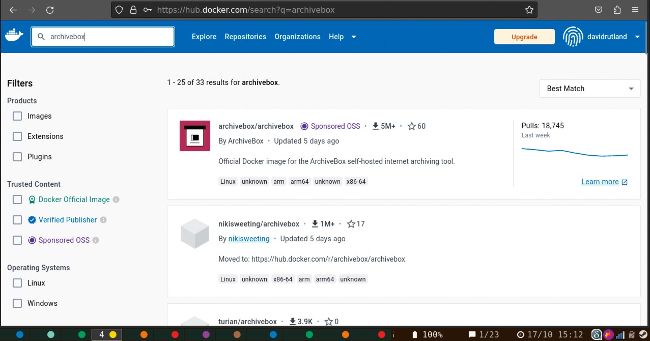

Docker Hub is one of the largest container registries. While you can access it through your web browser, some people prefer using the terminal.

Instead, containerisation offers a nice middle ground without too many compromises. Each containerised app comes with everything it needs to run – and the specific version it requires. Any libraries, dependencies and other files are a specific version, and guaranteed to work with minimal fuss.

Everything in the container is isolated from the rest of your system – so if, during an upgrade, a dependency develops a breaking change, it’s not going to affect the many and varied versions in your containers. Everything carries on as normal, and what once could have been a crisis isn’t even noticed.