A COLOSSAL SECRET

Ian Evenden discovers how British WWII braniacs, faced with an impossible task, helped save millions of lives and invented the computer as we know it

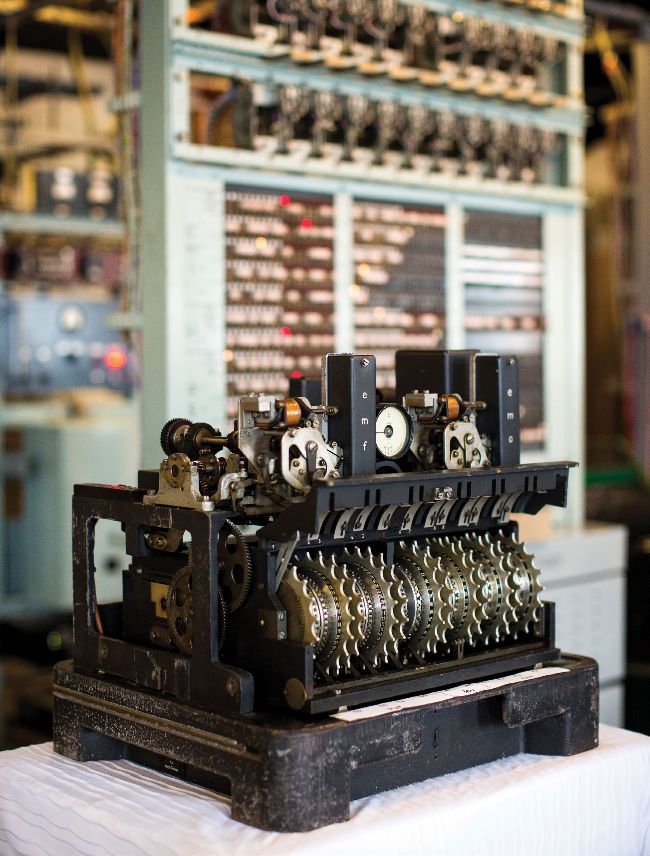

A Lorenz SZ42 cipher machine on display at Bletchley Park museum.

© JACK TAYLOR/GETTY IMAGES

Your country is at war, and you start picking up directional radio signals that sound like nothing you’ve ever heard before. The enemy is highly mechanized, makes use of the latest technology, and has a record of using complex codes and ciphers in its transmissions. This is something new, however. Instead of the dots and dashes of the Morse code you’re used to intercepting, this sounds like a harsh wailing.

These days, we’d probably equate the sound with a 56K modem, but back in the 1940s, it was known as teleprinter code. Nazi high command, not content with the “unbreakable” Enigma cipher it used to spread orders among its companies and brigades, was also using a machine for higher-level communications called the Lorenz SZ that British codebreakers had never seen, and would not see until the end of World War II. Despite this, they were able to deduce how it worked, and crack the encipherment.

This is the story of a country house in England full of mathematicians, crossword enthusiasts, the occasional genius, and a man from the postal service more used to creating automated telephone exchanges. Together, they read German military communications and shortened WWII by up to four years, saved possibly millions of lives, and created Colossus, the first programmable electronic computer, in the process.

This is a complicated story, and we’ve had to leave bits out, but bear with us, there’s still a lot of backstory. The tale of how the British, Alan Turing in particular, cracked Enigma, opening up Nazi communications, and making it possible to anticipate their every move is already fairly well known, but it has some parallels with the decryption of the Lorenz machine that can’t be ignored. The Nazis had mechanized the sending of secret messages, so a mechanized approach was needed for reading them. Lorenz had similar weaknesses to the Enigma, especially if you could be confident of the content of certain parts of messages, such as ending everything with “Heil Hitler,” for example.

Enigma was an electro-mechanical machine with three, sometimes four, rotor wheels and a plugboard. Input came from a keyboard, and its output was a lamp that lit up behind a grid of letters. The rotors moved every time a key was pressed, one full rotation triggering the next one to move, then the next. The plugboard swapped letters over, so connecting A to S always switched those letters. With three rotors from a set of five in use, and 10 connections on the plugboard, the machine was capable of nearly 159 quintillion (18 zeroes) combinations. Adding a fourth rotor, as the German Navy did, just made things worse.

Lorenz had 12 rotors, and acted as an add-on to a teleprinter machine (you type at one end, the message comes out printed on paper tape at the other), but otherwise operated in a similar way. Once the machine’s settings for the day were entered, however, it was much more automatic. The enciphered text was encoded as a 5-bit Baudot code (International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2) for transmission, which made use of a modulated on/off signal—binary, in other words—that was the source of the modem-like screeching the British listening stations were picking up.

“It was a binary machine, but not understood as a binary machine,” says Paul Gannon, author of Colossus: Bletchley Park’s Greatest Secret. “They used a different terminology at the time—mark and space. They didn’t think of it as zero and one; that’s a backward projection from what we know now.”

The Lorenz machine then encrypted the Baudot further with a Verman stream cipher. Ten of the 12 rotors in the machine generated a key stream in two groups of five, which was combined with the plaintext using a logical operation known as Exclusive Or (XOR—see table on page 51). The remaining two wheels added a pseudorandom “stutter” to the key stream, complicating it further. Each rotor had a different number of cams on it, which could be raised or lowered to create the wheel settings. The total number of settings is a number so large it would be followed by 150 zeroes (there’s 18 in a quintillion, remember).