THE MOJO INTERVIEW

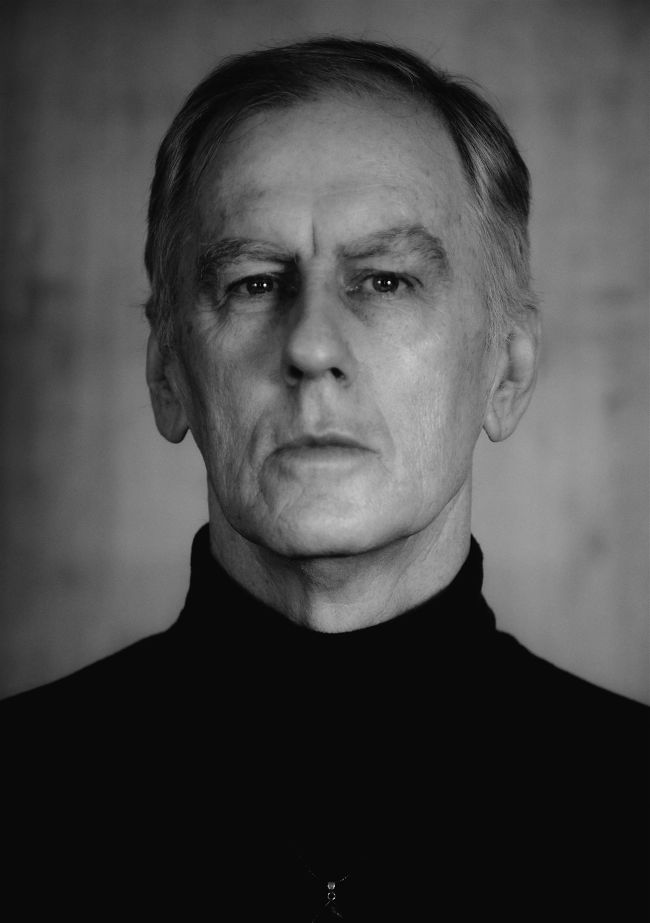

Brisbane’s bohemian king of lyrical intrigue choogles on, through the shadowed ruins of The Go-Betweens and current family adversity. What keeps him writing, singing? “As long as there’s more than 50 people listening, that’s all I need,” says Robert Forster.

Interview by IAN HARRISON

Portrait by STEPHEN BOOTH

TO HIS ADMIRERS, A NEW ROBERT FORSTER album is always a cause for excitement. Yet the announcement of The Candle And The Flame on October 16 came with a revelation. “In early July last year,” he wrote, “Karin Bäumler, my wife and musical companion for 32 years, was diagnosed with a confronting case of ovarian cancer.”

The situation reflects in the album in subtle ways. Recording began at the couple’s home in Brisbane in September 2021, with son Louis – of recently disbanded indie rockers The Goon Sax – among an intimate circle of players, and finished in early March this year, just as Karin’s chemotherapy concluded. Created as the family faced a huge ordeal, it is as witty, warm, and idiosyncratic as Forster’s best work.

It’s the latest chapter in a twisting story that began in Brisbane in 1976, when Forster met fellow singer Grant McLennan and formed The Go-Betweens. Formalised two years later, theirs was a unique songwriting partnership of point and counterpoint, with McLennan the poetic, melodious romantic to Forster’s more angled but no less impactful individualist. Together they made for a complete package of literary, lovelorn sunlight and shadow whose discography – LPs including 1986’s Liberty Belle And The Black Diamond Express and 1988’s 16 Lovers Lane (the “indie Rumours”, some called it) – inspires devotion. Despite a decade of graft, they never broke through, and split messily in 1990.

While Forster and McLennan both made excellent solo records, their wilderness-adjacent ’90s was followed by a Go-Betweens reunion and three more albums. The last of which, the exquisite Oceans Apart, could be their best. It was also their last: McLennan died suddenly aged 48 on May 6, 2006.

Forster’s solo career endures, and despite the trials his family have experienced, he remains a courteous and urbane presence. Right now he’s home in his suburban Brisbane bungalow, in his bookshelf-surrounded workroom where a few treasured guitars include a faithful, mid-’70s Guild acoustic bought in Greenwich Village. A framed photograph hanging over his desk depicts Go-Betweens Lindy Morrison, Grant McLennan and Forster with Tom Waits on the Bowery in the mid-’80s. “I asked him if we could have a shot together,” says Forster. “‘How do I know you’re any good?’ he asked. ‘Don’t worry, we’re good.’ I told him.”

Forster adds that he recently received an e-mail from Morrison about a newly discovered promo film for 1983’s classic single Cattle And Cane, and asks about Roxy Music’s latest London gig (“Was Bryan Ferry doing the little sort of shuffly dance, you know, like swinging the hips? He was? Good!”). MOJO remarks that new song I Don’t Do Drugs I Do Time – where the sober-since-’97 Forster asserts that his recall of the past is more mindwarping than any narcotic – seems to reorder and edit the events of previous decades. “You can try, anyway,” says Forster, a trim 65. “The past I find really rich. Someone says, ‘Oh, 1994,’ and I can just go right there. I can do details.”

When you’re sitting for the MOJO Interview, that’s just as well.

How do you come to make music at a time like this?

After Karin’s diagnosis, we were just really knocked out. Everything had changed. And so then Karin and I started, just late at night, playing these songs to get us out of what she was in, and what we were all experiencing. Let’s just do something, and you know, the beauty of music, the wonder of music… it just allowed us to float away. There was no intention at the start to make a record. None. It was purely to play music for music’s sake, and what the music gave us.