A Pilgrim’s Progress

Love them or loathe them, cover versions provide an insight into an artist’s influences. This spring, Van der Graaf Generator’s Peter Hammill releases his very first collection of them, taking listeners on a musical trip around the world with songs he’s translated himself. Prog catches up with the visionary artist to explore his journey from chorister to the genre-defying musician behind In Translation.

Words: Dom Lawson Portrait: James Sharrock

Maverick. Visionary. Prog’s perennial Renaissance Man. Punk-approved eccentric. After more than 50 years of active service in progressive music, Peter Hammill has earned all these titles and more. Always positioned to the left of the prog mainstream and seemingly impervious to the passing of time and trend, he’s amassed an extraordinary catalogue of music, both as a solo artist (36 studio albums and counting!) and with the legendary Van der Graaf Generator: the band he co-founded in 1967 and that currently exists as a trio, with Hammill alongside Hugh Banton and Guy Evans. By any sane reckoning, he’s one of the most important and influential figures in the history of prog. But what’s less frequently acknowledged is that Peter Hammill’s music, whether solo or with Van der Graaf, sounds like absolutely nothing and nobody else. In fact, it never has.

“To be honest, I’ve never been much of a listener to other people’s music.”

After a comparatively long gap between solo records, Hammill is to release his first ever covers album, In Translation, in May. It’s a highly revealing piece of work: a collection of mostly European songs, including works by Mahler and Rodgers and Hammerstein, translated by the man himself and reimagined with his customary skewed flair. Both a self-evident love letter to Europe and a wide-eyed experiment in dismantling and reconstructing other’s work, In Translation sounds entirely unlike anything else one might hear in 2021. And that’s exactly how Hammill likes it.

“I’m completely comfortable with that,” he tells Prog. “I’ve never really wanted to join in. I suppose the entire career has really been about trying to do something and getting it slightly, wonkily wrong. When I started writing proper tunes, I guess the subjects of the songs were a little bit out of the ordinary, and I didn’t want to repeat things, so very early on I veered away from verse, chorus, verse, chorus. I can’t explain why, but from a very early stage I was taking a few turns to the left, away from the main drag.”

Peter Hammill’s latest album, InTranslation.

One of the great joys of Peter Hammill’s music is how relentlessly inventive and unpredictable its creator has been over the last five decades. Having applied his singular vision to everything from tear-jerking ballads to abstract noise, he remains incredibly hard to pin down sonically. Interestingly, Hammill is endearingly unsure where his musical vocabulary comes from. He cites his parents’ love of musicals as an obvious starting point, noting that he grew up hearing West Side Story blaring from the family record player and that “it must have seeped in somewhere”. But the real starting point for his fantastic musical voyage came when Hammill was packed off to boarding school as a child, ended up singing in the choir and had a moment of revelation that set his artistic wheels in motion.

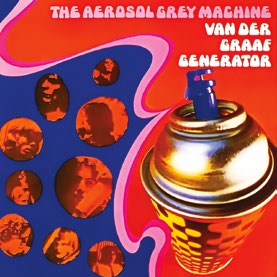

VdGG’s first album, The AerosolGreyMachine (1969) and below, the band in 1968.

“Although it had a connection to Van der Graaf, Fool’s Mate was obviously not remotely in Van der Graaf territory, even though the guys were playing on lots of it.”

BARRIE WENTZELL

“It was my first actual experience of, ‘This is music, this is great!’” he recalls. “I was a treble, at the junior school, going up to the main school for the Hallelujah Chorus. I’d only known the existence of trebles and altos at that point, so to suddenly be in a stall with basses and tenors, I thought that was absolutely fantastic. That was the first time I got that feeling that, wow, music is fantastic stuff. My voice broke not long after that and there were a couple of years when I wasn’t that involved or interested in music, and then British beat groups happened. I became superkeen on that, and then the blues thing too. I became enthused about the whole thing, but I didn’t think I would be doing it for the rest of my life.”

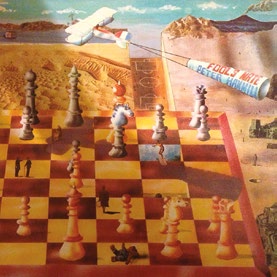

Hammill’s solo debut, Fool’sMate (1971).

As it turns out, Hammill has made music for his entire life, although he cheerily admits that his first bona fide musical efforts were somewhat wide of the desired mark and could easily have stopped his career dead in its tracks.

“As a result of the beat groups and finding out about blues, I started to write these desperately poor blues songs, without any of the life experience required!” he says with a chuckle. “I had a harmonica, then eventually I got a guitar and started doing the same thing on guitar. I guess I was 14 or 15. By 16 or 17, I’d started writing some tunes, some of which eventually turned up in the body of work, not with the original lyrics, but the tunes stuck.”

Freed from the blues, Hammill’s next move would prove to be the most important he would ever make. Arriving at Manchester University in the mid-60s, he swiftly joined forces with fellow aspiring musician Chris Judge Smith, and formed Van der Graaf Generator. At that time, the chances of having a successful career as a musician were slim at best, and yet after barely a year, the band were offered a contract by Mercury Records. Sensing an opportunity that may well have not been repeated, Hammill grasped the music biz nettle and set forth on a career he had never really expected to have.