GUY TALK

On the eve of his farewell tour, living legend BUDDY GUY looks back on his nearly 70-year career (and a particularly unforgettable Fender Bassman amp)

BY ANDREW DALY

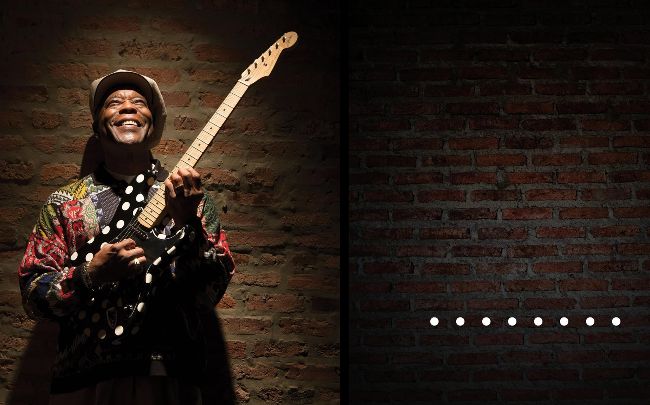

Buddy Guy at Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago, November 18, 2012

NELS AKERLUND FOR THE WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY IMAGES

HE MIGHT NOT

have admitted it then, but when Eli Toscano signed a 22-year-old Buddy Guy to his first recording contract with Cobra Records in 1958, Toscano undoubtedly knew Guy was special. Unlike anyone before him, Guy reshaped the sound of the electric guitar, pushing the blues to its limits in the late Fifties and into the Sixties. Of course, when we look at the now 87-year-old bluesman on stage, years’ worth of polka dot-tinged exploits come to mind. But in his early days, Guy was as mild-mannered as they come. Profoundly religious and hailing from Lettsworth, Louisiana, Guy’s formative years were more about survival than chasing dreams. But it didn’t take long for Guy to catch on with Cobra and later Chess Records as a session man, a period when he received his “first real education on guitar,” he says.

“I was never someone who would jump out in front of Junior Wells or Muddy Waters,” he adds. “When I walked in, I said, ‘It’s time for me to go to school.’ And that’s what I did. They’d put me in the corner, and when it was time to play, I’d play. And when it was time to learn, I’d learn.”

“But I’ve always been quiet,” Guy says. “I remember going into those studios with all these crazy, loud men who were all yelling. And whenever they’d see me in the morning, the first thing they’d say was, ‘Oh, good morning, motherfucker.’ And then, I’d go back in the corner, and when they needed me, they’d say, ‘Come over here, motherfucker,’ or ‘Turn that guitar up, motherfucker,’ or, ‘Hey, I told you to play this differently, motherfucker. So I was ‘Motherfucker,’ but I remember thinking, ‘Well, shit… I thought my name was Buddy.’”

By the late Sixties, having realized he had captivated the imagination of several young British bluesbreakers, Chess Records turned Guy loose. The result was 1967’s Left My Blues in San Francisco, which saw to it that Guy’s energetic style — which included the innovative use of a Fender Strat and featured hardrocking yet blues-soaked sounds — was finally allowed to be laid to tape.

But despite his influence, Guy was unable to break through to the mainstream. He soldiered on for another 24 years before going dormant in the Eighties. But in 1991, well past 50, Guy unexpectedly found widespread success with 1991’s Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues.

Looking back, Guy recalls the difficulties resulting from waiting so long to find success, saying, “It was hard because Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues was recorded when I was 55. I had gotten used to things being how they were and never expected anything big to come. I came from nothing, and to have Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues do so well, all I could think was, ‘Well… better late than never.’ I’ve been living by that motto ever since.”