LISP

LISP - exploring the original AI language

Discover one of the first programming languages, which Mike Bedford realises couldn’t have been more different from its early stablemates.

Credit: www.gnu.org/software/gcl/

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford found that getting to grips with LISP was a completely new experience, but he’s not convinced he’ll be embracing it in the future, despite its obvious quirkiness.

We can’t trace its fortunes year on year, but according to the TIOBE Index, LISP was the third most commonly used language in 1988. Today it’s at position 29, and while that’s a substantial drop since its heyday, we don’t think it’s bad going for a 64-year-old language.

In the previous instalment in our series on classic programming languages, we examined I ALGOL, and this month we’re delving into another archaic language, LISP. However, the fact they both date back to the 1950s is about the only thing the two have in common; in most other respects they couldn’t be more different. In all probability, virtually all languages you’ve ever used are of the type referred to as imperative languages. LISP, on the other hand, is a declarative language. To put it simply, programming in an imperative language involves defining a set of operations that, when executed sequentially, provide the desired functionality. The fact that there’s an alternative might be surprising, but in a declarative language, the end result is defined, leaving the system to figure out how to achieve the goal.

The two approaches have been likened to the instructions provided with a piece of self-assembly furniture. In the imperative approach, the instructions comprise a detailed list of instructions; with the declarative method, you’re just shown a picture of the assembled furniture. In fact, this isn’t our first foray into declarative programming in recent months. In LXF293,we learned about Prolog, the language that almost vanished into obscurity in the 1980s before making a recent come-back, fuelled by the AI revolution.

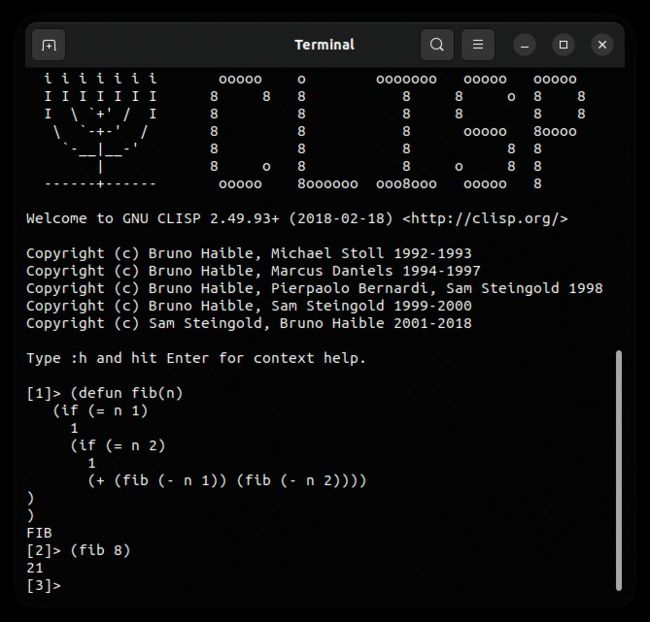

No IDE here – the Clisp interpreter runs in a terminal window, which is as close as you’ll get to the teletype on which the original LISP implementation would have run.

Part four!

Don’t miss next issue, subscribe on page 16!

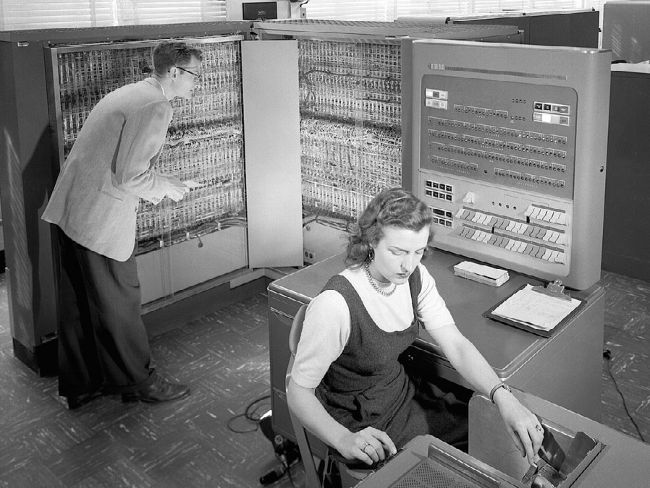

It’s becoming something of a tradition to show the computers on which our classic languages were launched, so here’s a photo of an IBM 704 mainframe, which was LISP’s first platform.

A declaration for LISP

We need to define LISP more accurately by saying that it’s not devoid of imperative features, and while that’s probably true of most declarative languages, LISP is more imperative than Prolog, for example. So, you could use LISP to write the sort of programs you’re familiar with, but that wouldn’t be making the best use of it, nor would it be a good language in which to write that imperative code.

A less formal definition is that it’s organised primarily around expressions and functions rather than statements and subroutines, though that takes us into the vagaries of semantics. Rather more helpful in pure functional languages, data flows through functions but has no separate existence of its own. But we have to point out that LISP isn’t pure in that respect.