Le Mans

Ahead of the centenary of the world’s greatest race, we catalogue 100 historic moments that helped define the legend of the Grand Prix de Vitesse et d'Endurance

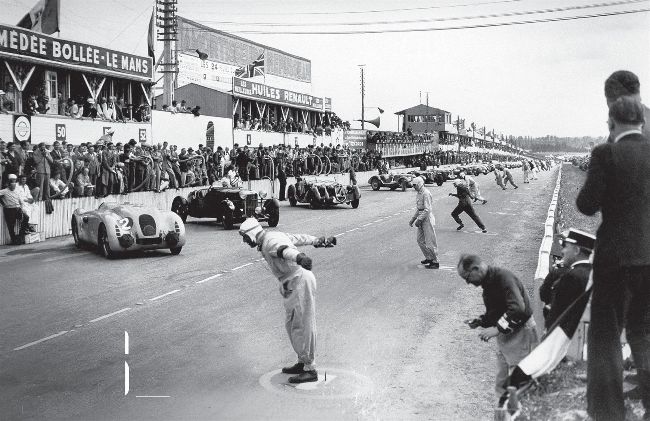

Less than three months from the start of World War II, drivers run to their cars at the start of the 1939 Le Mans 24 Hours. It would be 10 years until the race would return

GETTY IMAGES

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

How did we decide which moments should make the list? The brief was never about statistics, we wanted instead to focus on key moments that came to define Le Mans and helped the race transcend the usual motor racing histories. As such we include seminal moments and forgotten footnotes; tragedies as well as triumphs.

Our panel of experts comprised of Damien Smith, Gary Watkins, Paul Fearnley, Andrew Frankel, Robert Ladbrook, Gordon Cruikshank, James Elson, Rob Widdows

100 1976 NASCAR rumbles to La Sarthe

Spurred by a new accord with Daytona (sound familiar?), two of NASCAR’s lesser teams were encouraged to race at Le Mans, despite a clash with the stock car race at Riverside. Hershel McGriff’s Dodge Charger, above, from California and a Ford Torino from ‘Junie’ Donleavy in Virginia headed over for incongruous novelty value – and little more. The Dodge’s 5.5-litre V8, used to high-octane gasoline, burned pistons and didn’t last a lap. But the Ford, shared by Dick Brooks and Dick Hutcherson, raced into the small hours before the gearbox failed.

99 1955 The race’s weirdest car turns up

You could see the thought process. Instead of having the engine in front of the driver, with the latter positioned to one side of the former, why not use one to offset the weight of the other, each travelling in their own pontoons clothed within a super aerodynamic shape? The result was the Nardi Bisiluro, a car so slippery it was reputed to be capable of over 135mph with a 750cc BMW motorcycle engine. A shame then that it was so aerodynamically suspect that it was blown clean off the track by a passing Jaguar D-type after the race was a mere six laps old.

98 2010 Mansell crashes out of debut

Nigel Mansell’s first Le Mans lasted all of 17 minutes when a blown tyre pitched his Beechdean-run Ginetta-Zytek into the barriers on the run to Indianapolis. The 1992 Formula 1 world champion, sharing with sons Greg and Leo, took the start in what proved to be his final comeback to racing. During the accident Mansell received a bump on the head from the side-impact structure, but he appeared to be fine immediately afterwards. Years later he claimed it had led to amnesia, which was cured by his new hobby: magic!

97 1981 Porsche 917 rides again

Lacking entries, the ACO opened the door once again to larger-capacity engines, which sparked a lightbulb for brothers Erwin and Manfred Kremer. Why not recreate one of the greatest and fastest Le Mans cars of them all? Porsche was underwhelmed, yet the Kremers borrowed a Gulf 917 on loan to the Midlands Motor Museum (!) to build a ground-up copy. But the car was slow and was eliminated early when Xavier Lapeyre was edged off by a backmarker, fracturing an oil line.

KLEMANTASKI/BERNARD CAHIER/GETTY IMAGES, DPPI

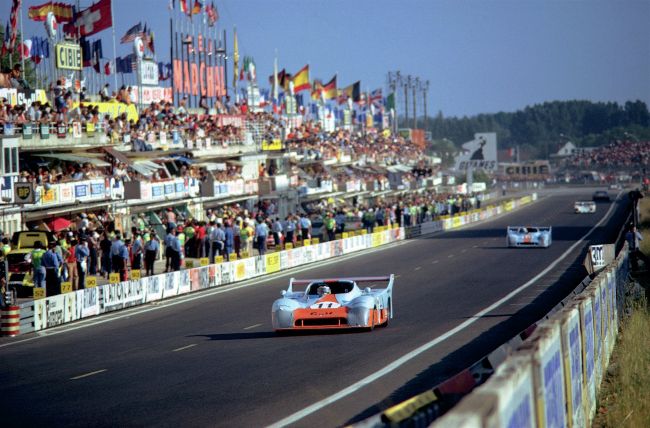

96 1975 A DFV defies the doubters

The Ford Cosworth Double-Four Valve V8 was already into its ninth season in Formula 1 when the engine claimed its first Le Mans win (Rondeau scored a second five years later). Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell dominated in a Gulf-backed Mirage run by JW Automotive, despite naysayers – including Keith Duckworth himself – claiming the Cosworth would never go the distance, largely because of a problem with torsional vibration.

The victory marked the first of three for the Ickx and Bell partnership, sports car racing’s most renowned double act. Bell first met Ickx at Ferrari in 1968. “I got to see Jacky and his insular attitude,” he says. “He wouldn’t say he was introverted – but he probably was. He never said more than he had to and never said anything to offend anyone. And he was effing quick. I was nowhere near him, but then again he’d been in F1 for two years by then. That was the difference. I started to learn from Jacky and the way he handled himself. I was lucky to be in the same team, breathing the same air.”

Bell was surprised to find himself paired with Ickx in 1975. “He wrote to John Wyer and said he’d like to drive for him and with me,” says the five-time Le Mans winner, who had already been on the driving strength of what was then known as Gulf Research Racing since 1973. “Wyer told me. Bloody hell. I had such a regard for Jacky. He came into the team and he never tried to say, ‘I’m Jacky Ickx, I’ve won this grand prix or that grand prix.’ He just said, ‘Tell me what to do, Mr Wyer.’ It was decided he’d do the start and I’d finish, because I had a reputation for finishing races, even though I’d only done Le Mans four times by then. I guess we did talk, but not to any great length. There was such experience in that team with John Wyer, who was like a headmaster. What he said you did, and we had this success together.”

The Gulf Mirage was a comfortable winner in 1975, and stands as one of only two independent constructors to win Le Mans post-war, the other being Rondeau in 1980

95 2003 Biela runs out of gas

Same team, same make/ model, same drivers: Frank Biela had scored a hat-trick in Joest-run Audi R8s from 2000, alongside Tom Kristensen and Emanuele Pirro. Only his Arena-run car remained the same in 2003 – and he suffered a very different result. Blocked by a backmarker from pitting for fuel, he backed off, weaved to slosh the dregs and churned the starter motor in a bid to coax the car around. It stopped before Arnage. Back with Joest, Pirro, and this time Marco Werner, he would win twice with Audi from 2006: the first and second wins for a diesel.

94 2002 Birth of the Le Mans Classic

Patrick Peter, previously a co-founder of the BPR GT series, launched this monster of a historic race meeting on the full 8.4-mile circuit to celebrate the heritage of the 24 Hours from the 1920s to the ’80s. He asked his friend, watchmaker Richard Mille, for advice on sponsorship. Mille offered support from his new eponymous brand – which had yet to reveal its first watch… More than 20 years later the biennial event is one of the most popular classic events on the schedule, and Mille is an entrant in the contemporary race.

DPPI, GAMMA-KEYSTONE VIA GETTY IMAGES

93 1952 Levegh’s solo disappointment

He looked older than he was, but 46-year-old Pierre ‘Levegh’ was fit thanks to a background of ice hockey and tennis. As a result, he felt sure that he was up to it. He did not feel the same way about his Talbot-Lago: a worrying engine vibration had kicked in and its rev-counter had packed up. His less experienced co-driver would just have to wait. And wait. And wait.

Levegh was holding first place by halfway, several laps ahead of a pair of Mercedes-Benz. The German firm was returning after 22 years, its air of efficiency undiminished despite an undeniable weight of emotional luggage. Quick in practice and along the straight, its gull-wing coupés began their push too late and Levegh continued to lead. Some thought the Paris garage owner was lapping unnecessarily quickly – 15sec faster than the winning Jaguar at the same stage the previous year – but he was unwilling to break a long-held rhythm selected to suit his and the car’s unusual circumstances. The impossible was looking possible – until the cause of that vibration revealed itself with a little over an hour remaining. A bolt in the centre bearing broke French hearts.

Levegh so nearly completed a feat now impossible when he drove his Talbot-Lago for 23 hours straight, until a central crankshaft bearing bolt ended his run

92 1990 Pareja breaks down

Jesus Pareja collapsing into the arms of his Brun Motorsport team down at the old signalling pits after Mulsanne Corner in 1990 encapsulated the emotional rollercoaster that is Le Mans. There were just 15 minutes remaining and the Spaniard was on course for an unlikely second place between a pair of Silk Cut TWR Jaguars when his Porsche 962C ground to a smokey halt.

Brun wasn’t up there among the favourites at the start of Le Mans ’90. Less so after a few hours when the Swiss entrant’s star driver in its lead car, Oscar Larrauri, fell ill after a heavy accident in a Saturday morning support race: the Argentinian would end up driving fewer stints than planned. The workaday Pareja and amateur Walter Brun, the owner of the team, had to do much of the heavy lifting through the race. Their task was helped by a special wing developed by Brun. The factory Joest 962s ran in traditional low-downforce spec, but Brun believed that with two chicanes now interrupting the Mulsanne Straight, more downforce was required. It was spot on.

Brun’s canniness and the heroics of its unfancied drivers came to nought. The smokey retirement was the result of a split oil union.

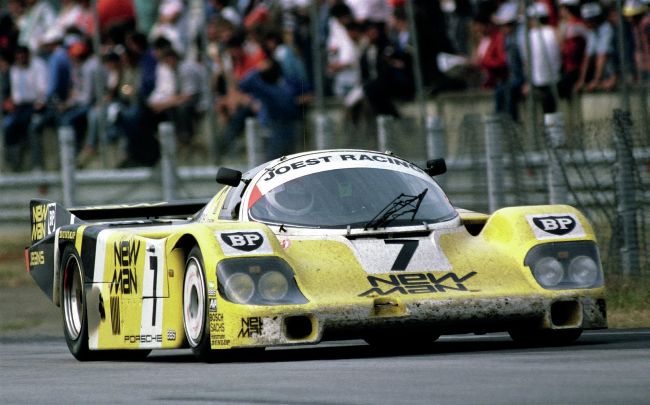

91 1985 Joest beats the Porsche factory

Winning in 1984? Great, but the Porsche factory was absent. Now the Rothmans cars were back – and Joest’s New Man 956 beat them anyway. The customer had pulled a fast one with 10% better fuel consumption, collaborating for a while in slipstreams with Richard Lloyd’s Canon car. As the works cars ran into trouble, 956-117 became the second car to win in consecutive years (after GT40-1075 of 1968-69), travelling 117 miles further than it had done 12 months earlier, with more than 100 litres of gasoline still unused. Sensational.

New Man, same result. Joest proved that privateers could still beat factory cars in 1985

90 1950 Eddie Hall’s successful solo drive

It is well remembered that in 1952 Pierre ‘Levegh’ nearly won Le Mans after driving solo for over 22 hours (see #93). It is scarcely remembered at all that, by that time, one Eddie Hall had already successfully completed the race solo two years earlier. What’s more he did it in a Rolls-Royce-built ‘Derby’ Bentley that was 16 years old at the time of the race. When asked by DSJ the secret to spending 24 hours in the cockpit without relieving himself, Hall is reputed to have replied: “Green overalls, old boy!”

GETTY IMAGES, GRAND PRIX PHOTO

89 1962 Chapman blows his top

The debacle of the Lotus 23 of 1962 put

Chapman at odds with the ACO

The generous rewarding of efficiency as well as performance was the perfect showcase for Colin Chapman’s ‘added lightness’ approach. His lithe Lotus 11 won the 1100cc classes of 1956 and 1957 by finishing seventh and ninth respectively; and a 750cc version won the Index of Performance as well as its class in the latter year. His 1300cc Lotus Elite won its GT class every year from 1959 to 1964 as well as the Index of Thermal Efficiency in 1960 and 1962. This, however, brought him increasingly into conflict with French manufacturers who had by now given up on overall victory and had found solace in the smaller classes. For several years Chapman’s father Stan had greased the wheels with a lunch here, a gift of pipe tobacco there, and Lotus had been fine. That changed in 1962.

The astounding performance of the Lotus 23 in Jim Clark’s hands at the Nürburgring 1000Kms grabbed attention. The ACO had its own ideas and rules – to which Chapman’s new design did not comply: oversized fuel tanks; too great a turning circle; insufficient ground clearance; and – mon dieu! – six studs on the rear wheels and just four on the fronts. To be fair to the scrutineers, the car was clearly unready. In Chapman’s defence, those scrutineers were being pernickety. This time it could not/would not be shrugged off: fix it by midday tomorrow or you’re out!

Lotus bust a gut to comply, Chapman working through the night on four-stud fixings and flying the parts out. When the chief scrutineer expressed a preference for six studs, Chapman argued furiously but got a steadfast “non”. The 23s were thrown out. An immediate threat never to enter again caused the organisers to call a meeting of supposedly calmer heads in Paris. But the Lotus boss was simmering. The figure Chapman jotted down when asked to calculate losses incurred, with a view to their being refunded, has not been revealed. But it caused the ACO’s chairman to bluster. The threat became a vow: Team Lotus and Le Mans were done.

Remarkable though it seems, no all-female crew has yet beaten the 1930 finish of Odette Siko and Marguerite Mareuse, who took the wealthy Mareuse’s Type 40 Bugatti to seventh place overall. Two years on, with male co-driver ‘Sabipa’, Siko placed fourth in her own 6C-1750 Alfa Romeo, which remains the highest-ever Le Mans finish for a female driver. Siko went on to contest rallies and to captain an all-female team which set speed records at Montlhéry.

88 1930

all-female finish

Remarkable though it seems, no all-female crew has yet beaten the 1930 finish of Odette Siko and Marguerite Mareuse, who took the wealthy Mareuse’s Type 40 Bugatti to seventh place overall. Two years on, with

Not bettered in almost 100 years, but could changing times give us a female winner?

87 1995 Mario Andretti’s ‘win’

In 1966 26-year-old hotshot Italian-American Mario Andretti, the reigning USAC champion but almost unheard of in Europe, had his first crack at Le Mans driving a Holman Moody works 7-litre Ford GT40. His race ended with a blown head gasket in the night.

Thirty seasons later, aged 55 and now a legend, he was back at Le Mans with his best chance of victory, and a chance to join Graham Hill as the only other person to have won the F1 title, Indy 500 and Le Mans.

He was in a Porsche-powered Courage, one of a handful of prototypes against an army of GT1 cars. Sharing with Le Mans veteran Bob Wollek and 1993 winner Eric Hélary, this was also one of the best driver line-ups. But the rulemakers limited prototype fuel tanks to just 80 litres, GT cars to 100.

It was all looking good despite the filthy weather until Mario came across one of the Kremer cars running slower than expected in the Porsche Curves, sending him into the wall in avoidance. It took six laps to repair. At the finish the Courage was second, one lap down on the leading McLaren and gaining. As Andretti told us: “We were first in class, so you’re a winner, right…?”

86 2010 Peugeot’s titanium conrod weakness