Filling The Empty Spaces

– EIGHT YEARS THAT CHANGED PINK FLOYD FOREVER

In 1980, Pink Floyd took to the stage at Earls Court, the cavernous 18,000-seater exhibition centre in west London. Booked for six nights in early August, the group performed a show that systematically parodied the very notion of an arena concert, introduced by an over-the-top MC, before sending four musicians onstage wearing Pink Floyd life masks; a surrogate band, proving that audiences at that distance could actually be watching anything. If that wasn’t enough to emphasise the dislocation, a physical wall was built between artist and audience made of 450 cardboard bricks.

The Wall became Floyd conceptualist Roger Waters’ most complex idea, a reaction to the general isolation in his role as conflicted multi-millionaire socialist, but specifically at the dislocation he felt as his group played live to ever bigger, increasingly soulless arenas. Always a band received with earnest silence from their fans, yet since the global success of 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon, rowdy elements of the crowd, especially in North America, asphyxiated the already slender rapport Waters felt with his audience.

But how did it come to this? How did a band, so experimental, stately and well-mannered get to this point? It all begins in exactly the same place, Earls Court, seven years earlier in May 1973.

There was much talk in early 1973 of Earls Court opening its doors to live concerts, yet there were few acts that could fill a hall of such size and scale. Built between 1935 and 1937, the storied venue was constructed on a triangle of land between train lines that had been used for

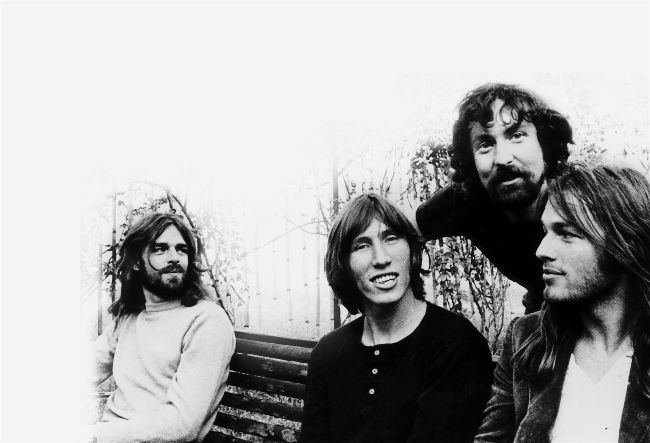

Happy bunnies: Pink Floyd in 1973.

Image: GEMA Images/IconicPix

“Roger started getting really upset later, after Money became a success. We became more famous and the gigs got larger; intimacy was lost.”

Ginger Gilmour

The two shows Pink Floyd played at London’s Earls Court in May 1973 marked a quantum leap for the group out of the ballrooms and theatre circuit into the arenas, stadiums and fields, where their concerts would remain for the rest of their career. Thanks to the worldwide allure of their eighth album, The Dark Side Of The Moon, their controls seemed to be set; any intimacy and direct connection with the audience – never something highest on Floyd’s priority list – was over. Prog explores those shows and their impact on the group in the following years.

Careful with those facts, Eugene: Daryl Easlea

entertainment grounds since the late 1880s. Its spectacular Art Deco/ Moderne style was designed by American architect Charles Howard Crane, famous for his ‘movie palaces’ of North America, most specifically in Detroit. The venue opened on September 1, 1937 – 40,000 square feet of space, complete with an indoor pool – with a chocolate and confectionery exhibition. From then on, it became the go-to venue for large-scale events such as the Royal Tournament, the Ideal Home Show, the 1948 Olympics and the Boat Show, where the indoor pool would be filled with almost eight million litres of water. But not live performances by rock bands. Yet.

For large concerts, London was served by Olympia, just up the road from Earls Court, with its 10,000 capacity. Jimi Hendrix and Floyd themselves had played there as part of Christmas On Earth Continued and, later, in one of his few ill-fated solo gigs, so did Syd Barrett. There was also the Empire Pool Wembley – again a 10,000-seater – which had opened

ROB VERHORST/REDFERNS/GETTY IMAGES its doors to concerts since 1960 with the NME Poll Winner shows.

After The Beatles had played to 57,000 at Shea Stadium in 1965, plus Woodstock in 1969 and the Isle Of Wight Festivals of ’69 and ’70, rock promotion became big business. And ‘big’ was the operative word – the bigger the better. The idea of festivals was now established, so if they could draw tens of thousands, surely the right band could fill a mere 18,000 seats in an arena. To facilitate this, a new breed of UK concert promoter was coming through such as John and Tony Smith, Harvey Goldsmith, Maurice Jones and Mel Bush.

“All the elements came together, as we presented the piece in its most developed version.”

Nick Mason

The idea to put on live shows at Earls Court came from showbiz impresario Robert Paterson and boxing promoter Jarvis Astaire (the man later responsible for bringing WWF to these shores).

“Patterson came from the classical scene, very old-school,” former London agent and Thin Lizzy co-manager Chris O’Donnell recalls. “I used to see Jarvis around town a lot. I don’t think there was a pie that he didn’t have a finger in. He once claimed he was offered the management of the Fabs but turned them down because his wife didn’t like them. Pure fantasy!” But, of course, an element of fantasy is what is needed to pull off feats on such a large scale.

The old Earls Court exhibition centre, now sadly – yet somehow inevitably – demolished.

Firstly, Mel Bush was contacted about which acts of his he thought he could promote there. He had not one, but two of such magnitude: David Bowie and Slade. At opposite ends of the glam phenomenon, both had ardent fanbases that could guarantee sales. If the teenyboppers could potentially fill it, so could Pink Floyd’s fans, especially as The Dark Side Of The Moon looked as if it would be their biggest release yet. Negotiated by the team at housing and homeless charity Shelter, Floyd agreed to play a benefit concert. As ticket sales (priced at £2, £1.75 and £1) far exceeded capacity, a second date was added. And so, on May 18 and 19, 1973, the group played two nights there, one of only three shows they played in the UK in that particular year. They already had a taste of larger shows as they had played Wembley’s Empire Pool the previous October, and understood that the sound was so important to these halls. Their US tour in March saw them playing venues between six- and 12,000-seaters.