TUTANKHAMUN

How Egypt’s legendary boy king came to power and who was really in control

Written by Garry J Shaw

Illustration by: Joe Cummings

EXPERT BIO

GARRY J SHAW

Garry Shaw is an author and journalist covering archaeology, history and world heritage. He has a PhD in Egyptology, and his new book The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy Who Became King, will be published by Yale University Press on 11 October.

Follow him on Twitter @GarryShawEgypt and Instagram @garryjshaw

Tutankhamun – originally called Tutankhaten – was born around 1329 BCE. This was a time of great upheaval in Egypt, when the prince’s father, King Akhenaten, had reformed the country’s millennia-old traditions. With Queen Nefertiti, he had turned his back on the gods in favour of an obscure deity the Aten, or sun disc. As Akhenaten’s reign progressed, the god Amun, king of the gods, was targeted for attacks. The king’s followers smashed Amun’s statues across Egypt and scratched away his name from monuments. Amun represented all that was hidden, so Akhenaten perhaps regarded him as the antithesis of the Aten’s all-encompassing, life-giving light.

But as the years passed, other gods were attacked too. To symbolise Egypt’s new beginning, Akhenaten moved the royal court to a newly built city in the desert, which he called Akhetaten – the Horizon of the Aten – today called Amarna. For years, people hauled blocks of stone from nearby quarries to build its temples, and worked in the intense heat making mud bricks for elite villas and palaces. The homes of the poor grew around these villas, and as the city developed, its workers died in large numbers; malnourished, overworked, and often young, they were buried on the outskirts of the city and forgotten. They paid the price for Akhenaten’s dreams.

With this dramatic shift in religious devotion, Egypt’s art style changed too. Directed by the king, the Amarna artists produced statues and carvings quite unlike any that came before or after him. Despite wearing the traditional regalia of a pharaoh, Akhenaten was carved with a round belly and spindly legs and arms – far from the youthful, muscular and fit bodies that pharaohs typically chose for their official art. Temples changed too. Gone were their dark and mysterious sanctuaries, where the gods’ statues stood in shrines, awaiting gifts and praise from priests. Temples to the Aten were open to the sky, embracing the sun’s rays, which reached down to touch hundreds of offering tables laden with food and drink. This was the new Egypt in which Tutankhamun grew up.

28

Nefertiti was not Tutankhamun’s birth mother, but would have been an important influence on his life

“As a child, Tutankhamun must have been heavily influenced by his father’s new vision for Egypt”

Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten and one of the king’s sisters. He spent his earliest years with his wetnurse, Maia, who later had a tomb built for herself at the ancient necropolis of Saqqara. Within, she included a scene of the young prince sitting on her lap. Around age four, while Amarna remained under construction, Tutankhamun began his education. One of his tutors was a man named Sennedjem who, among his duties, taught the young king to ride chariots, perhaps near the city of Akhmim where the tutor would eventually be buried. To keep his hands and feet safe from rocks and sand as he rode along, Tutankhamun wore gloves and socks – not unusual for a charioteer. He carried his love of riding into his teenage years.

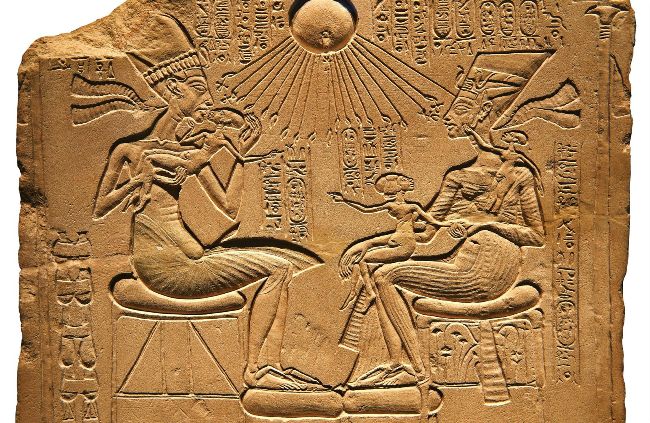

A stele from Amarna showing King Akhenaten (left) and Queen Nefertiti (right) with three of their daughters beneath the Aten’s rays. The future Queen Ankhesenamun is on Nefertiti’s shoulder

The young prince also learned how to read and write. He owned scribal equipment that bore his name, and dipped his red ink-covered pen into one water pot so often that the pot became stained. If he followed the typical curriculum of a scribal student, Tutankhamun first studied the cursive script hieratic, used in administration and correspondence, before moving on to the sacred hieroglyphs found on the walls of tombs and temples. With his tutors’ guidance, he would have spent a great deal of time copying and recopying set texts, including already ancient classics such as The Tale of Sinuhe, about a courtier who fled to the Levant, and wisdom texts attributed to the great kings of the past. Certain teachings perhaps came directly from Akhenaten. The king saw himself as a teacher to his courtiers and composed hymns to the Aten, which were copied onto their tomb walls. As a child, Tutankhamun must have been heavily influenced by his father’s new vision for Egypt. He would have accepted the closure of the ancient temples and the destruction of divine statues as normal.