GETTY IMAGES/ALAMY/DREAMSTIME/EMILY BRIFFETT, COURTESY OF MANCHESTER MUSEUM, THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

1 The aim of mummification was preservation

FALSE

(sort of)

Generations of schoolchildren have been taught that ancient Egyptians treated the remains of high-status individuals to preserve them for the afterlife. Yet this idea is shaped by modern – which is to say modern western – cultural expectations of what the dead should look like, linked to the fact that the first Europeans to investigate ancient Egyptian mummies in the 18th century were themselves interested in embalming techniques. These researchers were keen to preserve their own dead just as they had been in life – so they looked as if they had simply fallen asleep. Even today, people take comfort from this approach.

The ancient Egyptians, however, did not intend their dead to be seen by the living, and were apparently less concerned with preserving the transitory appearance of a human during their lifetime. Rather, they focused on transforming the body into an enduring and perfect effigy resembling one of their immortal gods.

None of the gory details of mummification are depicted in Egyptian art. Instead, our knowledge comes from the Greeks and Romans, both morbidly fascinated by mummies, who left accounts of a practice they thought weird. They describe how mummification dehydrated the body, made it hard and brittle. Once anointed with scented oils, the body resembled the expensive woods from which sculptures of the gods were carved.

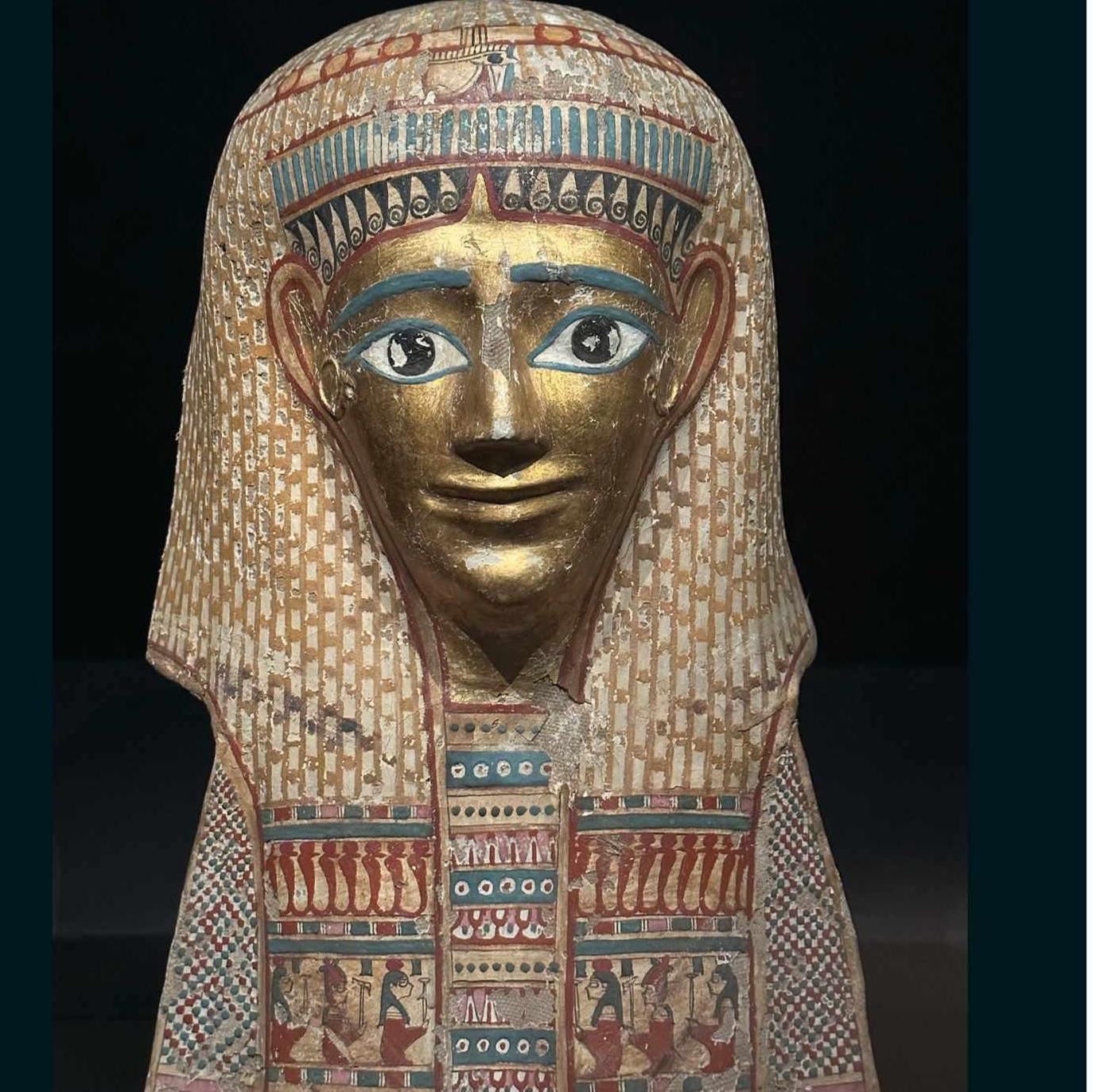

In ancient texts, Egyptian deities are said explicitly to have flesh of gold, bones of iron or silver and hair of lapis lazuli, a blue semi-precious stone. So those who could afford it might be supplied with a gilded mask and a blue-painted hair covering to emulate these divine features.

The facial appearance of a mummy mask is the product of the shaping of plaster and linen on an idealised and reusable mould – so was never intended to be an accurate likeness of the deceased. In inscriptions, the dead are often referred to in divine terms, with men and women alike given the designation Osiris, the god of rebirth. From around 300 BC, women alone were referred to as Hathor, also known as the ‘Golden One’, the afterlife goddess par excellence. For the wealthy, therefore, mummification was about transformation in order to achieve immortality – not about preserving the body in the form of that person while alive.

The death mask of an unnamed but wealthy woman. Mummy masks were never intended to be an accurate likeness of the deceased

2 The brain was always removed from a mummy’s body

FALSE

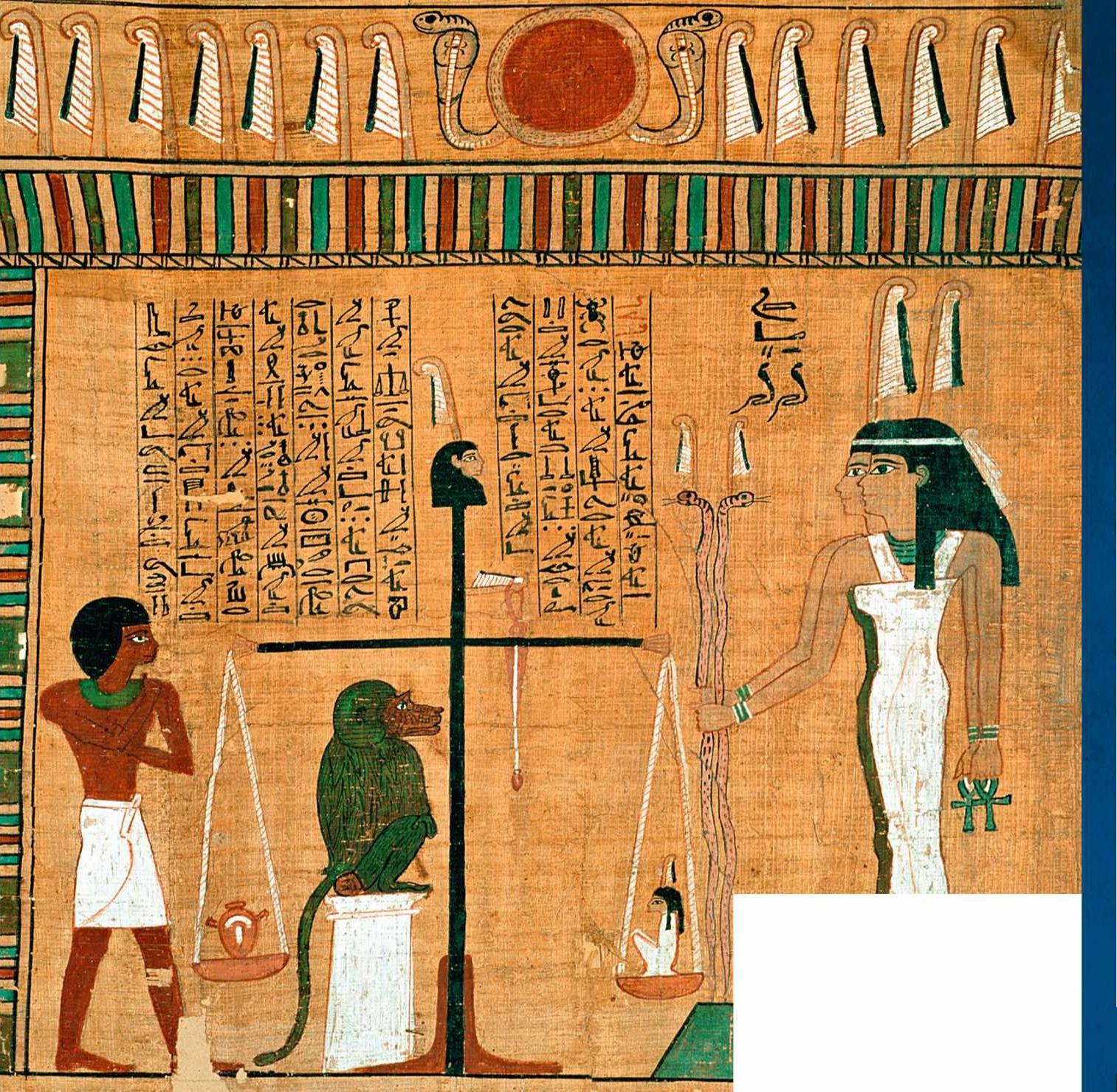

A heart is weighed in judgment in a detail from the Book of the Dead. The fate of organs during the mummification process isn’t as cut and dried as we might think

GETTY IMAGES

The ancient Egyptian concept of post-mortem judgment is illustrated by a scene in the funerary composition known as the Book of the Dead, first written on papyrus during the 16th century BC. This depicts the heart of the deceased being weighed on a set of scales against a feather representing Maat – the concepts of truth, order and justice. It is often assumed that, for this reason, the heart had to be kept in place in the body during mummification, while the other internal organs might be removed and placed in containers that became known to early Egyptologists as canopic jars.