COMPUTE THIS

The history of supercomputing turns out to be a tale of eccentric inventors, nuclear weapons, and a constant need to one-up the other guy. Ian Evenden explains.

On July 25, 1946, the US military carried out a nuclear weapon test at Bikini Atoll, Micronesia

© GETTY IMAGES/JOHN PARROT/STOCKTREK IMAGES

As anyone who’s ever tried to work out a restaurant bill, including drinks, taxes, and tip, already knows, some math is difficult. Expand that by several orders of magnitude, and suddenly you’re simulating the effects of a nuclear bomb, or protein folding, or calculating how many oil rigs to send up the Bering Strait before winter, and your needs go beyond mere computers. You need a supercomputer.

Established in the 1960s, supercomputers initially relied on vector processors before changing into the massively parallel machines we see today in the form of Japan’s Fugaku (7,630,848 ARM processor cores producing 442 petaflops) and IBM’s Summit (202,752 POWER9 CPU cores, plus 27,648 Nvidia Tesla V100 GPUs, producing 200 petaflops).

But how did we get to these monsters? And what are we using them for? The answers to that used to lie in physics, especially the explodey kind that can level a city. More recently, however, things like organic chemistry and climate modeling have taken precedence. The computers themselves are on a knife-edge, as the last drops of performance are squeezed out of traditional architectures and materials, and the search begins for new ones.

This, then, is the story of the supercomputer, and its contribution to human civilization.

DEFINE SUPER

What exactly is a supercomputer? Apple tried to market its G4 line as ‘personal supercomputers’ at around the turn of the millennium, but there’s more to it than merely having multiple cores (although that certainly helps). Supercomputers are defined as being large, expensive, and with performance that hugely outstrips the mainstream.

Apple’s claim starts to make more sense when you compare the 20 gigaflops of performance reached by the hottest, most expensive, dual-processor, GPUequipped G4 PowerMac to the four gigaflops of the average early-2000s Pentium 4. For context, Control Data’s CDC Cyber supercomputer ran at 16 gigaflops in 1981, a figure reached by ARMv8 chips in today’s high-end cell phones.

Before supercomputers there were simply computers, though some of them were definitely super. After World War II, many countries found ways to automate code-breaking and other intensive mathematical tasks, such as those involved in building nuclear weapons. So let’s begin in 1945, and the ENIAC.

The CDC 6600 from 1964 is often considered to be the first supercomputer.

© WIKIMEDIA

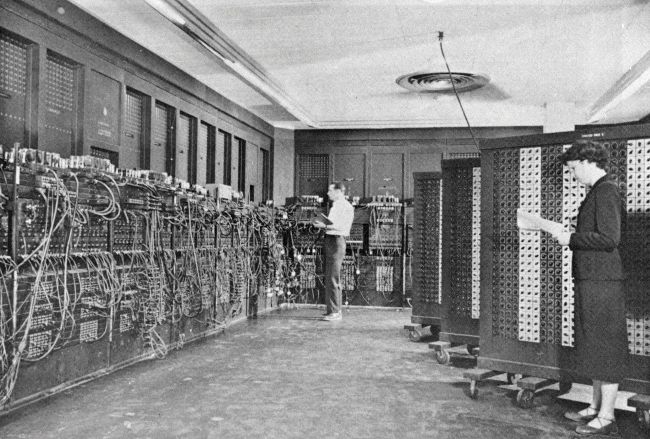

This programmable mass of valves and relays was designed to compute artillery trajectories, and it could do a calculation in 30 seconds that would take a human 20 hours. Its first test run, however, was commandeered by John von Neumann of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and consisted of calculations for producing a hydrogen bomb. ENIAC was programmed, and provided its output, using punch cards, and a single Los Alamos run used a million cards.

ENIAC was upgraded throughout its life, and when finally switched off in 1956 (having run continuously since 1947, pausing only to replace the tubes that blew approximately every two days) it contained 18,000 vacuum tubes, 7,200 crystal diodes, 1,500 relays, 70,000 resistors, 10,000 capacitors, and around half a million joints, all of them soldered by hand. It weighed 27 tons, and took up 1,800 sq ft, while sucking down 150kW of power. Its computational cycle took 200 microseconds to complete, during which time it could write a number to a register, read a number from a register, or add/ subtract two numbers. Multiplication took the number of digits plus four cycles, so multiplying 10-digit numbers took 14 cycles, or 357 per second.

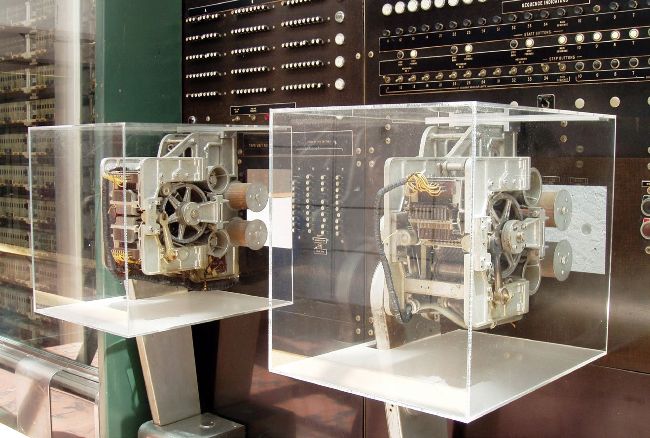

Parts of the Harvard Mark I computer on display. Made by IBM, and proposed in 1937, John Von Neumann ran the first program on it in 1944 under the Manhattan Project.

Early computers owed much to the design of the ENIAC and the British Colossus. Breaking enemy codes was still a high priority, as was finding ever more efficient ways to blow things up with both high explosives and pieces of uranium. It’s around the early 1960s, though, that things such as processors and memory became recognizable. Take the UNIVAC

LARC, or Livermore Advanced Research Computer, a dual-CPU design delivered in 1960 to help make nuclear bombs, and the fastest computer in the world until 1961. The LARC weighed 52 tons and could add two numbers in four microseconds.

TECH EXPLOSIONS

There was a burst of computer development in the early 1950s. IBM had been in the game since WWII, its Harvard Mark I electromechanical machine coming online in 1944, with one of its first programs, again run by Von Neumann to aid the Manhattan Project. In 1961, Big Blue would release the IBM 7030, known as Stretch, the first transistorized supercomputer and the fastest computer in the world until 1964 (a customized version of Stretch, known as Harvest, was used by the NSA for cryptanalysis from 1962 until 1976, when mechanical parts in its magnetic tape system wore out).

The ENIAC at the Ballistic Research Laboratory, Pennsylvania, circa 1950.

© WIKIMEDIA

Von Neumann was behind another computer, sometimes named for him, at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, which was in operation until 1958. This computer was the basis for a new generation, including the IBM 701, the ILLIAC I at the University of Illinois, and Los Alamos’ alarmingly named MANIAC I, which became the first computer to beat a human at a chess-like game (on a 6x6 board with no bishops to suit the limitations of the machine).