THE MOJO INTERVIEW

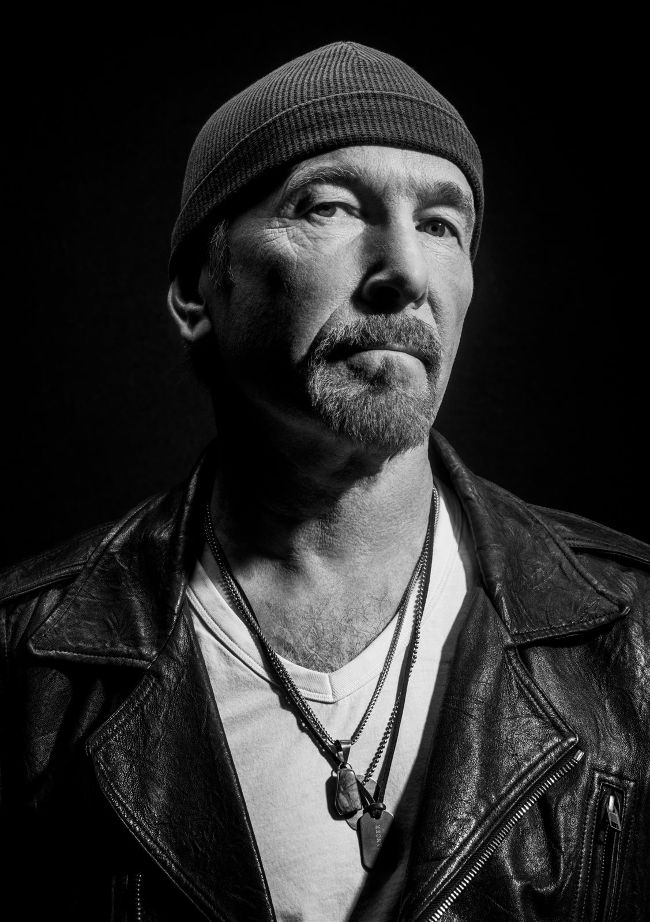

U2’s sonic scientist has just reanimated 40 of their classic songs: the latest experiment in six decades of tinkering, questioning, taking it all quite seriously. “Being in a band, we didn’t want it to be a trivial thing,” says The Edge.

Interview by KEITH CAMERON

Roger Kisby, Ward Robinson

DAVE EVANS STILL REMEMBERS HIS FIRST electric guitar, the one he watched his older brother Dick build in their family’s north Dublin garden shed. Two years later, Dave, by then known as Edge, along with the other three members of U2 spent the summer of 1978 in that same shed, rehearsing songs for their breakthrough demo tape.

“It was this gaudy yellow, Flying V kind of guitar, but it worked,” says The Edge. “I think there was a competition at school, so Dick took it as a sort of science project. I was in charge of helpful suggestions and encouragement. We both played it a lot.”

The last time Edge saw Dick’s science project it was flying through the air at Dublin’s Project Arts Centre, tossed from the stage during a show by the Virgin Prunes, the yin to U2’s yang on the city’s post-punk scene. Plenty more guitars have passed through his hands since. The Edge is as synonymous with the instrument as anyone from the rock era, thanks to his signature contributions to U2’s 45-year career, a bulging inventory of questing, minimalist flash.

MOJO catches up with The Edge in New York, roughly midway between Dublin and Los Angeles, the cities the 61-year-old calls home. owes its existence more than most to Edge’s musical curiosity, as 40 U2 songs are deconstructed and re-cast into often striking, lowkey contexts. Released to accompany Bono’s

He’s shouldering promotional duties for Songs Of Surrender, U2’s 15th studio album, one that recent memoir, Surrender, the album emphasises the co-dependent relationship between guitarist and singer. The Edge’s experimental urges, meanwhile, re-activate the band’s best art-rock instincts.

“It was a liberating experience,” he says. “Pure playfulness, and no expectation. Instead of designing the songs to work on a rock’n’roll stage, to connect with a large audience, we’re replacing that intensity with an intimacy.”

Our interview is four days before the official announcement of U2’s return to the rock’n’roll stage in a brand new Las Vegas venue. Predictably, then, Edge is guarded about details of ‘U2: UV Achtung Baby Live At The Sphere’, and its most contentious aspect: the absence of Larry Mullen Jr (“an amazing drummer and an integral part of what we do,” Edge says) to undergo and recuperate from surgery, and his replacement by the relatively unknown Bram van den Berg.

But if some fans can’t bear the idea of U2 without their founding heartbeat, how inconceivable would it be without its creative engine and, arguably, most distinctive component? The Edge hopes we’ll never have to find out.

“The thought that I can wake up one day, go to the piano or the guitar and write a song that’s gonna be around for hundreds of years – I’m inspired by that idea. The song is still such a powerful thing.”

Did making Songs Of Surrender cast any of your songs in a new light?

Quite a few. The lyrics particularly took on this completely different quality, because they’re the centrepiece of these arrangements. We started ➢

bumping into new lyric ideas. With Bad, Bono started writing it again, from the first-person this time. Sunday Bloody Sunday, the same – we got to the final verse and Bono says, “I think we can improve on that.” And with Stories For Boys, we took the scissors and completely rewrote that lyric from the perspective of now. Because Stories For Boys was written by a bunch of boys. We were 17 or 18. So now, we’re looking at those young guys, from this distance of time and experience, to give another light to what that song was about.