FILTER ALBUMS

Let’s get metaphysical

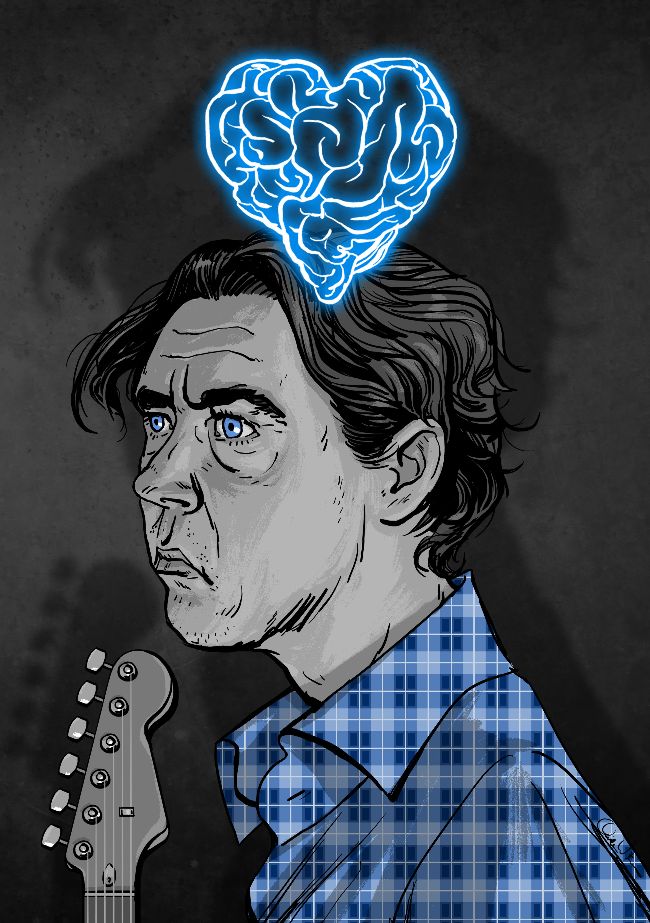

Does the body rule the mind or the mind rule the body? Californian singer-songwriter gets on the case with tenth album. By Victoria Segal. Illustration by Quinton Winter.

Cass McCombs

★★★★ Heartmind

ANTI-. CD/DL/LP

FLAT INSIDE THE sleeve of every vinyl copy of Cass McCombs’s 2019 album Tip Of The Sphere lay a paper tribute to British/Canadian artist Brion Gysin’s high-concept invention the Dream Machine. Bend the laser-cut sheet into a cylinder, direct an appropriate light-source, set it spinning along with the album on the turntable, and listeners could close their eyes and induce a f lickering hypnogogic state. (“I was an acid kid,” McCombs said in 2013, “anything that remotely suggested acid, I was there.”) While there are plenty of moments in the Californian wanderer’s back catalogue that would be complemented by such a device – Equinox from 2005’s PREfection, for example, with its thorny riff and reference to owls, wolves and “silverfish quilting testicle” – it’s better to keep your electrical brain oscillations about you when faced with Cass McCombs and his complicated work.

Since the low-grade, big-sky psychedelia of his 2003 debut A – atitle wildly promising a whole alphabet of releases – McCombs has been an uneasy and inscrutable figure on the singer-songwriter horizon. “I’m against extroverted personalities,” he said in 2016. “I’m against talking heads, I’m against cult of personality, rock’n’rollers who wanna kiss ass and make everyone like them.” Yet he’s not – no matter what his more f lorid moments of ink-and-scrimshaw storytelling or gnomic gnosticism might suggest – an artist out of step with the world. In 2012 he released a song called Bradley Manning; in 2020, he remodelled “misunderstood” early song Don’t Vote as Don’t (Just) Vote, featuring Angel Olsen, Bob Weir and Noam Chomsky – all useful co-ordinates for zooming in on McCombs’s patch of Americana.

BACK STORY: FISTIC MYSTIC ● The LP credits feature a quote from 12th century Sufi mystic Ibn Arabi (above): “My heart has become capable of any form/My heart has become receptive of every form.” What is McCombs’s take on the heart-mind divide? “The heart and the mind are like room-mates – they live together and they get on each other’s nerves sometimes, like room-mates do, but they need each other and when they find each other it’s a whole other spiritual feeling – awhole new character. Smoosh the two words together and it’s pretty simple in my mind.”

Heartmind is unlikely to break him out of the smoked-glass shell of cultdom, especially when astringent post-prog opening track Music Is Blue gyrates so aggressively on a ley line between Canterbury and Chicago. Yet this album does display notable lushness after its dour predecessor, its ember-like warmth fanned by backing vocals from Wynonna Judd, Danielle Haim, and Lily and Abigail Chapin. The arrangements bring out the ’90s Jim O’Rourke in his music, especially the gentle Latin American percussion of Krakatau.

The title track comes with a strong Elliott Smith mood, there in its use of specific street names (“at Turk and Taylor”, a significant San Francisco crossroads) and its struggle to master itself, to gain emotional control, ending in a diffuse, cottony sprawl of guitar, Uilleann pipes and Moog.

“Cass McCombs is looking at the world differently, watching as life strobes by in all its curious forms.”

“These are streets that I know well, that I’ve walked by millions of times,” explains McCombs.

“Everybody knows these intersections between realities and there’s a lot of people suffering at these crossroads, but the crossroads can also take you off into new possibilities and tangents.”

From the first track, McCombs is heading for those crossroads, on a mission to find out where the heart and mind intersect, what’s real and what’s not. He’s had issues with his muse before – as on cautionary allegory A Knock Upon The Door from 2011’s Wit’s End – but here the disillusionment seems profound. “Once upon a time,” it begins, like a fairy story, “I told myself music was all there was/Like a ghost town in quarantine/No way in/No way out.” It lurches and clangs, as if you need to hang on for dear life or one song has become too small to contain all the demands music makes upon him. Karaoke, meanwhile, initially seems like a smart idea for a love song, McCombs re-purposing the titles of standards to tell his story – “Are you going to Stand By Your Man?/Or is it just karaoke?” Yet it’s more than a neat pop gimmick, like bands putting “radio” in a song title: it quietly questions whether everyone lip-syncs to feelings they’ve heard before, seconding and thirding that emotion without experiencing their own response.

Yet there is a real emotional impact here. Heartmind is dedicated to three of McCombs’s friends who died in the past three years – Neal Casal, Love Is Laughter’s Sam Jayne and Chet ‘JR’ White of Girls – and it’s hard not to connect these losses to the record’s sense of urgency. Belong To Heaven is a beautiful elegy to a complicated person, somebody both “lunar” and a “grease fire”. “Call me anytime for bail/From the jail/In heaven,” sings McCombs, before the almost relentlessly angelic backing vocals flood back in. It’s moving in a way McCombs hasn’t always cared for – witty and strung with vivid images (“a rosary of Dos Equis beads”), yes, but also delivered with a conversational phrasing that underlines the humanity, the guilt, the love.

Even when he breaks into an impromptu literary lecture about Mary Shelley and Stephen Crane in the middle of antique reapwhat-you-sow lament Unproud Warrior, a song about a regretful young soldier backed by Charlie Burnham on fiddle and vocals, it’s for heartfelt reasons. “You were only 17 when you enlisted,” he sings, worrying at personal responsibility, growing up and the terrible passage of time and potential. “You remember SE Hinton wrote The Outsiders when she was just 15.”

Like Bill Callahan, also fond of writing about his various apocalypses, McCombs doesn’t always feel like the most reliable narrator. Most disturbing is the lovely chirrup of New Earth, a song set on “the day after the last day on Earth”, fluttering its pop wings as if there’s nothing to worry about. For all the joyfulness, it lands less like a utopian idyll and more like a wry comment on the “old” Earth – especially with its playfully vicious image of “Mr Musk”, “stewing in his bullion”. It proves that McCombs doesn’t need any dream machine to induce new visions: 10 albums in, he’s more than capable of looking at the world differently all by himself, watching as life strobes by in all its curious forms.

CASS SPEAKS! McCOMBS ON THE PAINFUL CREATIVE PROCESS, KARAOKE FUN AND MR MUSK.

“You have to draw blood a little.”

Cass McCombs speaks to Victoria Segal.

You once said making albums was becoming easier with time – where does Heartmind fall on the easy-difficult spectrum?

“I’m going to have to go back on saying that. It’s always difficult making records, for me at least. It’s a series of compromises. The song begins as this ethereal kind of idea and slowly gets brutally ground down to a crude piece of material – and of course, there’s millions of choices along the way, sacrifices. I’m not painting a very pleasant picture of the process but it’s about just enjoying the people you’re around for me. If I can enjoy the people I’m around, I think it’s going to be a beautiful recording. Did that happen this time around? One hundred per cent.”

Is every record disappointing to you, then?

“A little bit. Transferring something from the mind to wax is such a strange procedure – it’s like a medical procedure. Something that’s so open becomes finite, so there is a melancholy aspect in the creative process.”

Is Karaoke suggesting that music can become a substitute for real feelings?

“Karaoke is an allegorical kind of song about relationships. I’m always wondering if our thoughts and expressions are being fed to us in some sinister way and how do we really authenticate the true human? Sometimes, to authenticate what you’re feeling, you have to poke yourself, you have to draw blood a little.”

Is writing how you poke yourself?

“Of course. There’s lots of poking.”

You refer to lots of songs in Karaoke – do they have specific meanings to you?

“I guess they’re standards of the karaoke room and culture but woven in a kind of way that makes a narrative. Is that a culture I know well? I enjoy watching people, listening to people trying to interpret songs. So many people say they can’t play music, they can’t sing – but I think karaoke’s cool because it’s welcoming to all people. I don’t have a regular song, no.

I try to switch it up every time.”

Can you explain what the title means to you?

“It’s just the last song on the album. It’s about how the heart and the mind are like room-mates – they live together and they get on each other’s nerves sometimes, like room-mates do, but they need each other and when they find each other it’s a whole other spiritual feeling. A whole new character.”

Does the post-apocalyptic New Earth suggest that it’s better to burn everything down and start again?

“I didn’t think about it like that. Whatever our anxieties are about anything, there’s always a day after the bad day. Part of me was thinking about like Waiting For Godot or something like that, trapped in this constant anticipation of the next day.”

And you got to have a dig at Elon Musk?

“It’s not that person (laughs). It’s a totally different person named Mr Musk.”

Amanda Shires

★★★★ Take It Like a Man

ATO. CD/DL/LP

Shires enlists alt-pop producer Lawrence Rothman for heartbreaking ninth solo record.

You might sense an album opening with Hawk For The Dove – aBDSM track complete with a demand to “Mark me up” and abrasive Venus In Furs strings – is going to be intense.

But the much tougher stuff here is emotional. Shires makes a devastatingly calm appeal to her song’s subject not to avoid their emotional pain. “Stay right where you’re standing… See it to the end.”

While Empty Cups could be part of the Dolly songbook, Shires continues to step towards pop and away from the Americana that made her a star on her own, with husband Jason Isbell, and The Highwomen. The singer owns her sins on Here He Comes and Bad Behavior. She says the album is grounded in real life.

Maybe it’s fitting then, that there’s no resolution: “If anyone asks I’ll say what’s true, and really, it’s I don’t know.”

Chris Nelson

Andrew Tuttle

★★★★ Fleeting Adventure

BASIN ROCK. CD/DL/LP

Australia’s King Of Ambient Banjo is back!

If Joni Mitchell hadn’t already claimed the name 45 years earlier, Andrew Tuttle would’ve been well advised to retitle Alexandra, his 2020 album, The Hissing Of Summer Lawns.

Unlike Joni, though, Tuttle’s métier is a sort of balmy ambient Americana, his reveries located in the suburbs of his Brisbane hometown; tranquil and beautiful, but relatable rather than otherworldly. This sequel traverses reassuringly similar zones, with Tuttle’s banjo threading in and out of the FX atmospherics, and an expanded instrumental cast – notably fellow travellers Chuck Johnson and Luke Schneider on pedal steel – operating with equal subtlety. Saxophones and strings drift into focus, not least on the gorgeous Overnight’s A Weekend, where Steve Gunn also pops by to lend spiralling, Göttsching-esque guitar lines. Beautifully manicured, but perhaps next time a rewilding project might be in order?

John

Mulvey

Danger Mouse &

Black Thought

★★★★ Cheat Codes

BMG. CD/DL/LP

Super-producer and Roots rapper team up for old-school gold.

There’s a key quote from Black Thought on page 51 this month, when he says, “We made this record for people from a certain place and time who identify with specific aesthetics.” The aesthetic, specifically, is that of finely matured vintage hip-hop, full of cognoscenti nods and cratedigger samples: Black Thought quotes Rakim in the album’s first line, while Danger Mouse is cueing a chunk of Gwen McCrae’s 1976 quiet storm, Love Without Sex. Danger Mouse’s illustrious production CV is a big draw – one significant client, Michael Kiwanuka, drops in on Aquamarine – but it’s his classy discretion in play here, giving plenty of space for Black Thought, a rapper whose virtuosity can sometimes be overshadowed by Questlove and the other Roots. Raekwon, Run The Jewels and the late MF Doom guest too, but this is Black Thought’s show. As he asserts over a bumping Hugh Masekela loop on No Gold Teeth, “I won’t stop, won’t drop, won’t retire.”