Facilitated Communication Redux

Persistence of a Discredited Technique

BY STEVE SOBEL, M.D.

IMAGINE IF YOU WERE INFORMED THAT YOUR heretofore nonverbal, intellectually disabled child with autism actually had a brilliant mind merely needing the assistance of a simple technique to liberate deep thoughts, rich emotions, and aspirational dreams that had been imprisoned in his or her mind due to physical limitations alone. Purveyors of Facilitated Communication (FC) offer just such a promise to parents and to other family members, educators, and community support staff of autistic individuals.1 Despite a plethora of evidence long ago exposing FC as a sham, its use in many communities persists, as tantalizing promises, however false they might be, exert a potent appeal for those desperately longing for signs of hope. In fact, it not only persists, but in some areas of the U.S., including my state of Vermont where I am a practicing psychiatrist at a community mental health center, its use is being promoted and expanded.

FC originated in Denmark in the 1960s, but did not gain a foothold there due to the lack of evidence for its legitimacy. Nevertheless, an Australian author named Rosemary Crossley managed to resuscitate FC in her home country in the 1970s. It was imported to the U.S. in the late 1980s by Douglas Biklen, an American special education professor, establishing the Facilitated Communication Institute (FCI) at Syracuse University in 1992. Based on a claim that motor issues (apraxia) prevent these individuals with autism from typing on their own, the FC technique involves a facilitator who physically guides the nonverbal person’s arm or hand, thus enabling the individual to communicate by typing on a keyboard or letter board. (This is not to be confused with legitimate augmentative communication methods which use manual signs, picture exchange, voice output devices, etc. 2)

Parents, teachers and others were thrilled to learn that their children were not intellectually disabled after all; indeed, the eloquent and moving thoughts of their charges could now be expressed. Using FC, we would now know what these “prisoners of silence” were thinking and feeling.3What made this even more miraculous was that autistic individuals, even those raised in institutions, and who had not previously read books or received even a rudimentary education, were able to produce elaborate pieces of writing with flawless grammar and spelling. The individual frequently looks away from the keyboard while typing with just one finger—a feat surpassing the capability of even the most skilled typists who need to use both hands to keep their place on the keyboard.3

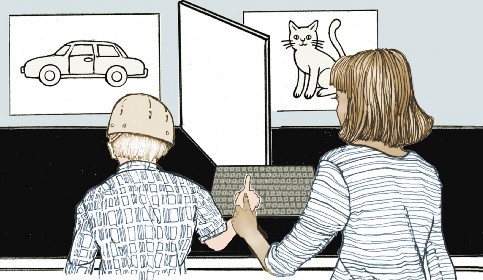

Do the words typed during FC come from the autistic individual or from the facilitator? In a test, each person sees a different picture. The autistic individual is asked to type what they see. In 180 trials involving 12 autistic individuals and 9 different facilitators not a single correct response was typed.3