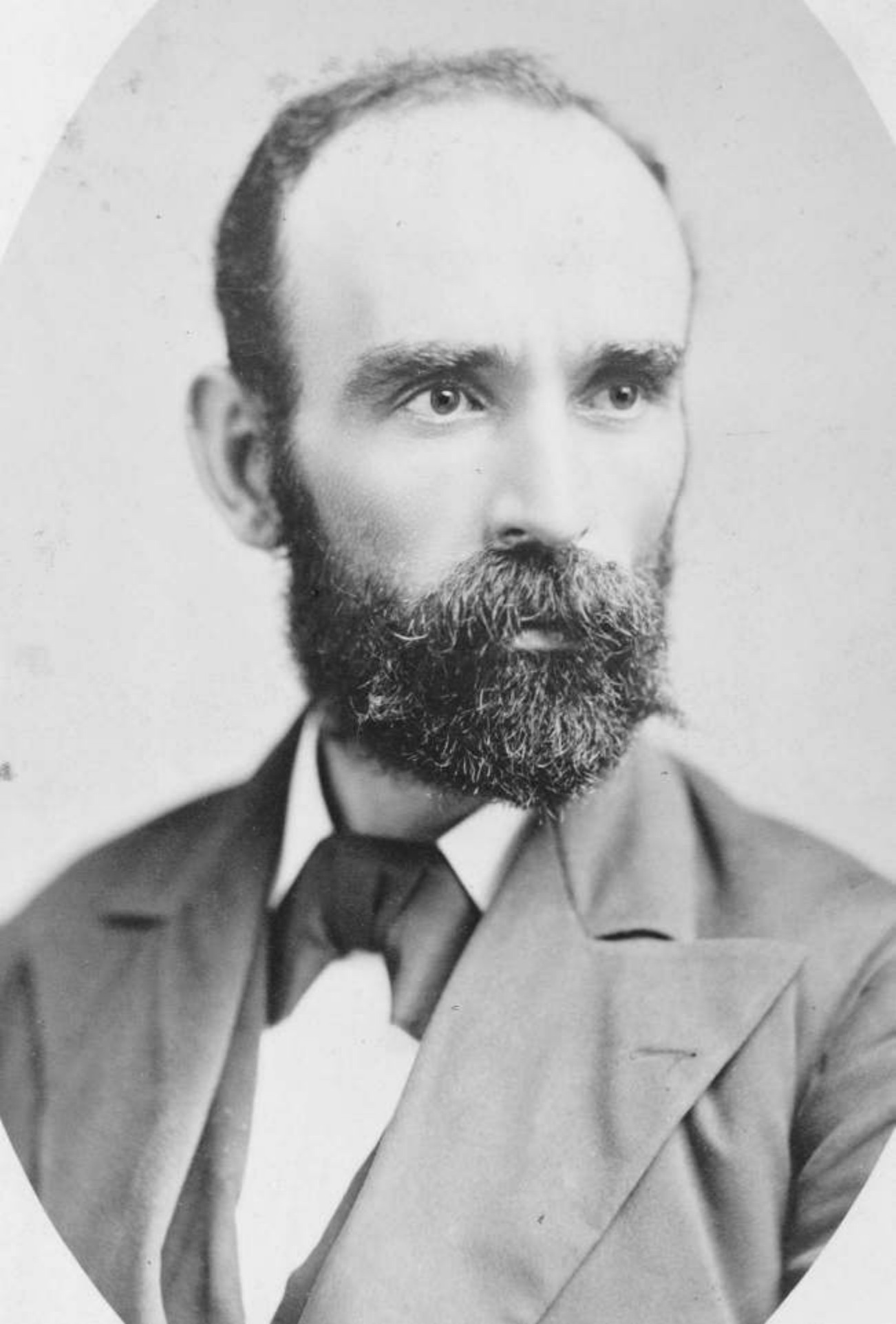

Michael Davitt c.1880

Michael Davitt was an important Irish radical, whose interests went beyond Ireland and took a varied and international dimension. Despite being born into poverty in county Mayo, in the west of Ireland, during the height of the famine, he was not an insular, provincial nationalist, even if he did possess many characteristics of an uncomplicated Irish nationalist. His most significant trait was that he was considered to be a ‘freelance radical’ – a man who embraced causes he simply believed to be right. His family were evicted from their small, subsistence holding in rural Mayo and forced to move to Lancashire in the 1850s, where Michael soon went to work in a local factory.

Following an industrial accident and the loss of his arm aged eleven, Davitt embraced the oeuvre of the local mechanic’s institute, reading Chartist literature and embracing the spirit of self-improvement and democratic fervour the movement fostered. He was acutely aware of the bitter legacy of dispossession and dislocation as a result of his family’s eviction, and this was formative for his later life as a radical; he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a group that fought for Irish independence from Britain through violent insurrection, and he spent seven years in prison as a result. He returned to Ireland following his release from prison and soon bore witness to the acute poverty of small farmers living on farms of marginal land in Galway and Mayo. He helped establish the Land League in 1879. It became a massive national movement – one of the largest in Europe – that campaigned for what was known as the ‘three Fs’ – fair rent, fixity of tenure and freedom of sale. Its campaign saw the introduction of the 1881 land act that recognised these, and he became known as the ‘Father of the Land League’. This act influenced Scotland’s crofter radicals as they campaigned for something analogous that eventually bore fruit through the 1886 crofters’ act

The end of 1882 saw Davitt commence his first tour of the highlands, stating that the tour was a radical and not an Irish mission

Following the passing of the 1881 land act, Davitt was left exasperated by the conservative hue that overtook Irish nationalism was consolidated following the signing of the Kilmainham treaty in 1882. This was an informal agreement between the British prime minister, William Gladstone, and the leader of the Irish parliamentary party, Charles Stewart Parnell, which saw Parnell promise to control violent elements within the nationalist movement in Ireland in return for Gladstone agreeing to do something about the level of rent arrears in the country. Davitt felt that this was a conservatising influence on the country, and he became jaded with the direction Irish nationalism was taking. He then turned his attention to the condition of the working class in Britain as Irish nationalism and British democracy became intertwined. Davitt had taken an interest in Scotland and the highlands from the early 1880s, but this article pays particular attention to his second highland tour in April 1887, during which he appeared as an antidote to Joseph Chamberlain’s anti-Home Rule rhetoric.

Henry George, Michael Davitt and land nationalisation

The Irish National Land League was officially established in Dublin in October 1879 and Davitt was a key figure in its foundation. By that December, Davitt realised that the highlands could potentially be an area for agitation, though there was little desire for such a campaign at the time. 1881 saw the establishment of the Skye vigilance committee by Angus Sutherland, who was a key figure in Davitt’s tour of 1887 and close confidant of his in Scotland. He had argued that every highlander was a born agitator because they had suffered either directly or indirectly from landlordism.