In 1971, President Richard Nixon and the U.S. Congress declared war on cancer. In 2016, President Barack Obama launched the Cancer Moonshot, a program to reduce cancer mortality and improve the lives of people with cancer. In 2010, I reviewed the progress of cancer therapy: its costs, efficacy, and adverse side effects (Spector 2010). I also proposed greater emphasis on the importance of preventive efforts.

I focus here on the progress since 2010 in adult cancer. Much of this is due to a new class of immunological drugs, principally check point inhibitors. I will attempt to place the facts in proper perspective after an overview of cancer data, the epidemiology, and treatment of adult cancer in the United States.

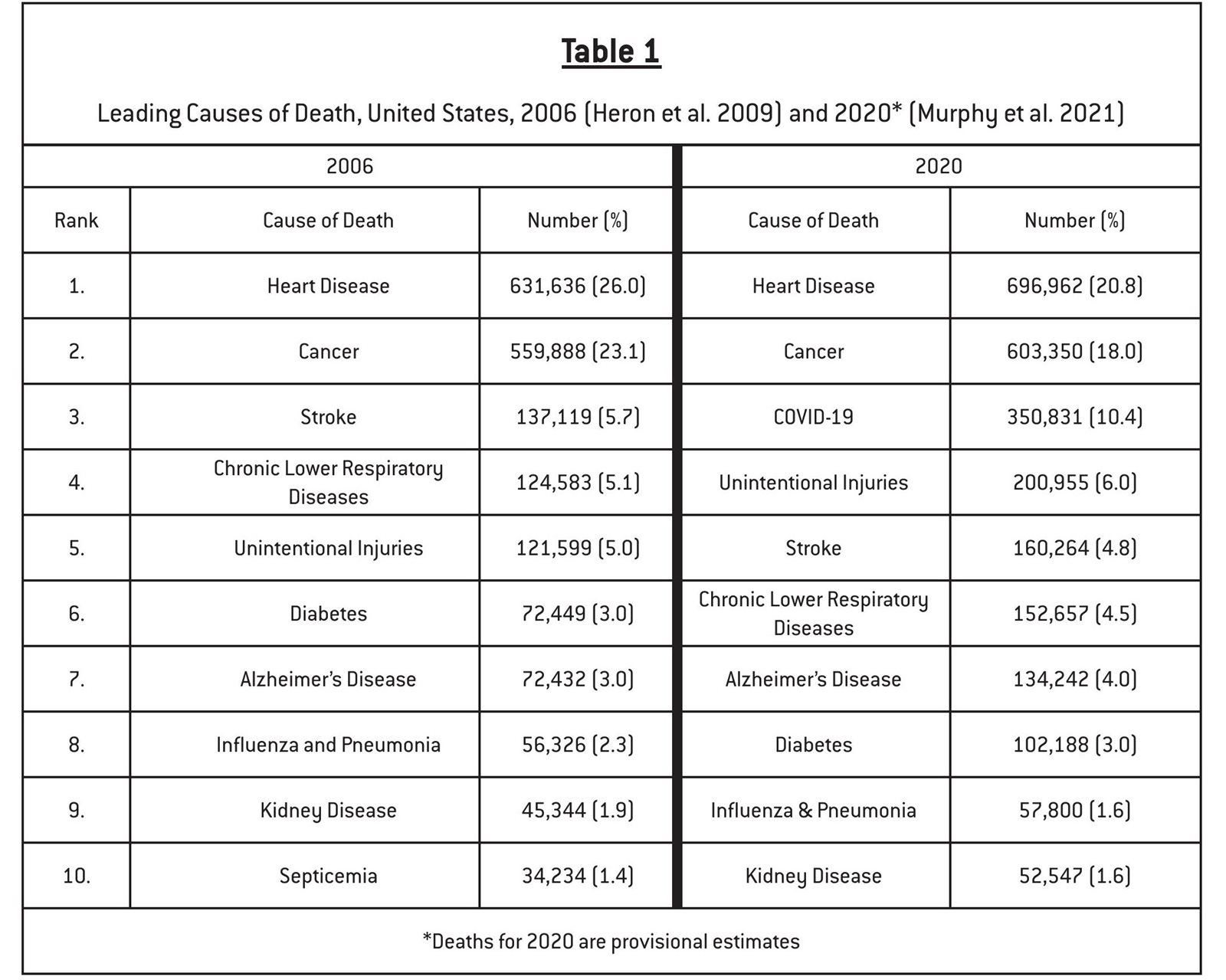

Cancer is and has been for many years the second most common cause of death in the United States, exceeded only by heart disease (Table 1). In contrast to heart disease and stroke, the death rates for which declined 70 percent and 78 percent, respectively, between 1950 and 2010, the death rate for cancer declined only 11 percent (National Center for Health Statistics 2022; Elfin 2022). The declines in heart disease and stroke result f rom improved treatment and prevention, especially the decline in smoking and advances in the treatment of high blood pressure and atherosclerosis.

Cancer is the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells. Although the body’s normally functioning immune system destroys most incipient cancers, some malignant cells develop mechanisms that block or avoid host immune systems, enabling the cancer to grow. Cancers are commonly described and studied based on the organ (e.g., lung, colon) afflicted. Cancers arising in different organs may have different causes and clinical behaviors. Cancer is described as local, regional, or distant (metastases). The five most common cancers in men are prostate, lung and bronchus, colon and rectum, urinary bladder, and melanoma of the skin; in women, breast, lung and bronchus, colon and rectum, uterine corpus, and melanoma of the skin are most common.

The rate of uncontrolled cell proliferation varies among different cancers. Some—notably prostate and breast—may grow very slowly, and patients with these cancers may survive many years even without therapy. Others, such as lung and pancreas, progress more quickly. Responses to cancer treatment may be classified as complete (cure), partial, or no effect. Knowing if a patient has been cured is difficult because some patients who have had a complete response may relapse. Partial success is described in various ways. A few examples from clinical studies include 1) median survival (that is, when half the patients have died); 2) overall sur vival at one year, two years, or five years; or 3) time to tumor progression.

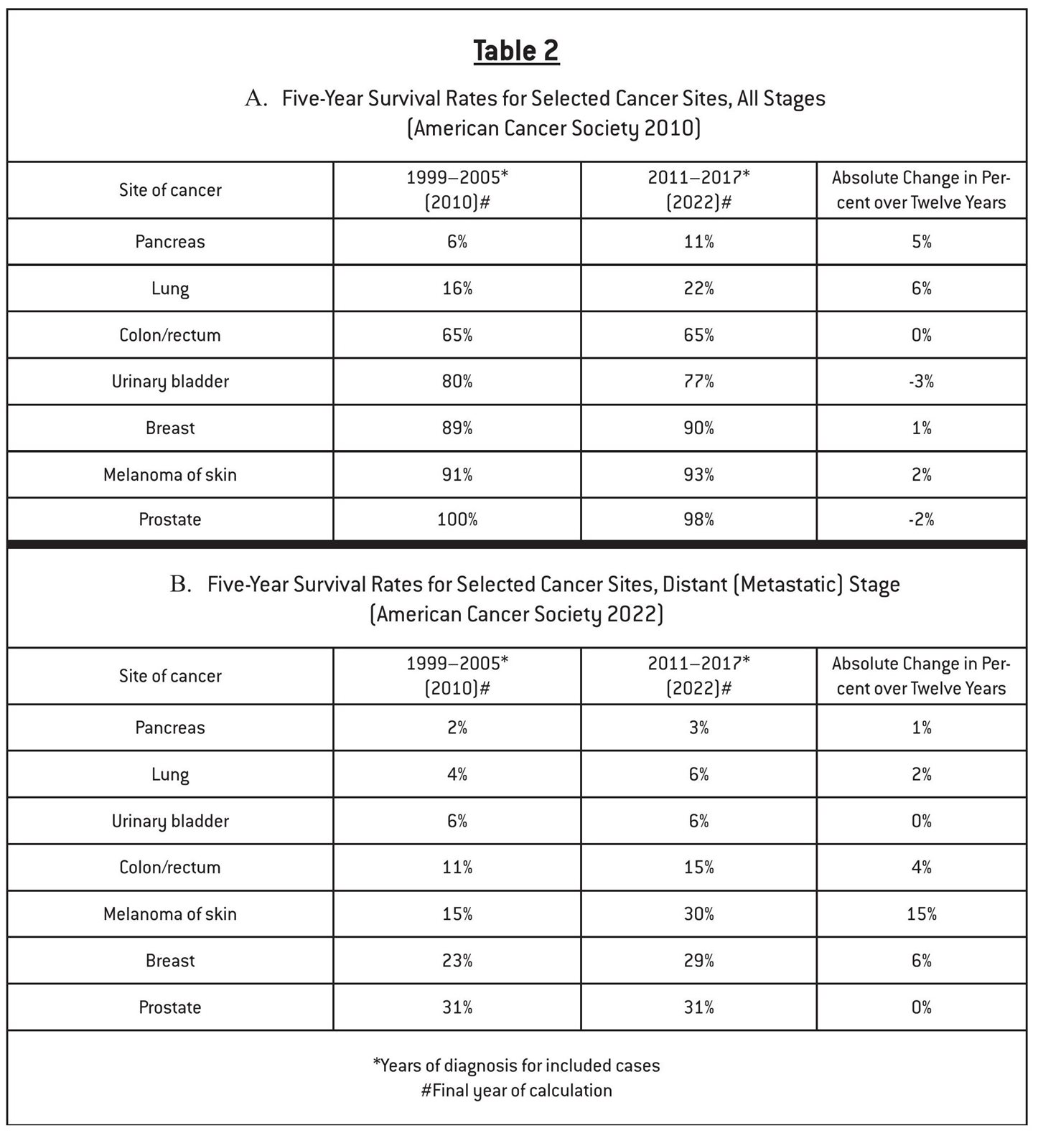

At the population level, progress is also measured in several ways. Monitoring incidence rates assesses progress in the prevention of cancer. Mortality rates may be reduced either by prevention or improved treatment. Five-year survival rates, the proportion of individuals who live five years or more after initial diagnosis, primarily assess progress in cancer treatment (Maruvka et al. 2014). In recent years, aside from the absolute increase of 15 percent in the five-year survival rates among patients with distant metastases of melanoma, the small changes in five-year survival rates suggest limited therapeutic success (Table 2). Long-term trends in cancer death rates are displayed in Figures 1 and 2.

Methodology: Accuracy and Generalizability

Data used to guide and monitor our efforts to reduce morbidity and mortality of cancer fall into two general categories: surveys and special studies to monitor trends and research to identify safe and effective treatments. A third general category, etiologic research, is also important but contributes little to our discussion about trends and treatment.

Information about the size and changes in the size of the problem over time come primarily f rom public sources such as death certificates for mortality rates and the federally sponsored Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program for incidence and survival data. The American Cancer Society commonly presents and summarizes these data in useful formats. Data f rom these sources are generally reliable but may be misleading. Consider, for example, a patient whose cancer is detected in a screening program and then treated. If the cancer is a slowly growing cancer, the treatment would appear to extend the patient ’s life even if the treatment is totally ineffective. Regardless of the efficacy of the treatment, the patient ’s life may appear to be extended simply because the cancer was detected at an earlier stage than it otherwise would have been. This type of error is referred to as lead-time bias.