LOUISE & LORNE: A ground-breaking royal marriage

This May marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Queen Victoria. Margaret Brecknell explores the marriage of Victoria’s daughter Louise – a match that went against the strict conventions of the time

Margaret Brecknell

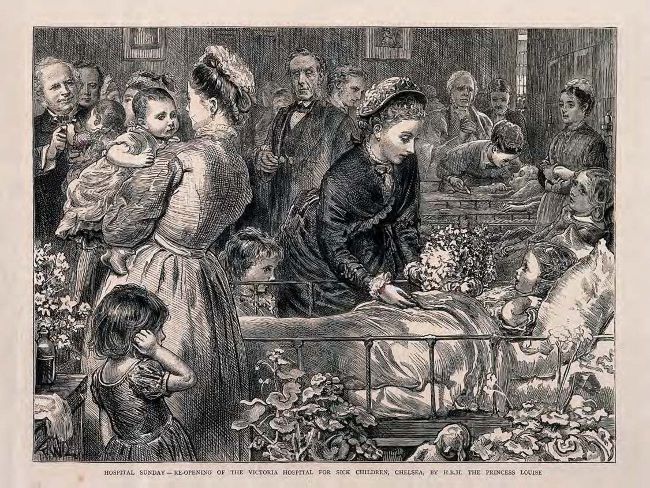

Princess Louise opening the Victoria Hospital for Sick Children at Chelsea in June 1876

With last year’s wedding between Prince Harry and Meghan Markle at St George’s chapel, Windsor, still fresh in the consciousness, it is timely to look again at a similarly groundbreaking royal marriage which took place at the same venue during the latter part of the 19th century. Indeed, it may be argued that it set the precedent for many royal marriages since. I am referring to the wedding of Queen Victoria’s fourth daughter, Princess Louise, to the marquis of Lorne, eldest son of the duke of Argyll.

The occasion of Louise and Lorne’s wedding on 21 March 1871 marked the first time that a legitimate daughter of the sovereign had married a commoner since Mary Tudor wed the duke of Suffolk in 1515. In her 1991 book Darling Loosy Elizabeth Longford notes that The Times of 1871 described Louise and Lorne’s forthcoming marriage as ‘revolutionary’. So what brought about this seemingly unexpected union and did it prove to be successful for the couple in question?

Princess Louise Caroline Alberta was born on 18 March 1849, the sixth of Victoria and Albert’s nine children. Clearly she was far from being her mother’s favourite child. In a letter of 1859 to her eldest daughter, Vicky, the Queen describes Louise as being ‘very naughty and backward though improved and very pretty and affectionate’. Louise’s father, Albert, seems to have tried to compensate for this lack of maternal affection by singling her out for special attention. However, life was to change forever for Louise and the other young royals with the death of their father in December 1861.

Inveraray castle at the turn of the 20th century

If life as a young princess had seemed stifling before, now it must have seemed suffocating to the teenage Louise. The royal court was plunged into a state of deep mourning which continued for years. The younger unmarried royal daughters were now required in turn to act as secretary to their grieving mother, taking on the practical business of dealing with the reams of correspondence with which Albert had dealt previously. This burden initially fell on the shoulders of Louise’s sisters, Alice and Helena. However, following their marriages it was Louise’s turn to take on this role.

For all Victoria’s earlier misgivings about her fourth daughter, Louise proved to be an adept and supportive companion. By the time of her twentieth birthday in March 1868 she was held in such high regard by her mother that an entry in the queen’s personal journal for that day reads: ‘She has much character, such originality, such an affectionate heart, also possesses a great taste and talent for art’.

By this time Louise was already looking for ways in which she could broaden her horizons and escape the stifling palace environment. She had already displayed an aptitude for sculpture, an art form that hitherto had been considered only suitable for men. Reluctant at first to support her daughter’s interest in this ‘unladylike’ artistic pursuit, Victoria eventually relented and in 1868 the Queen was even persuaded – uncharacteristically – to give permission for Louise to attend the National Art Training School in Kensington. Thus Louise became the first British princess to attend a public school, albeit only infrequently as she was often detained by her secretarial duties.