The Secrets of Stonehenge

It was a century ago that Stonehenge was gifted to the nation, but have we come any closer to understanding it? Miles Russell goes digging for clues

AKG IMAGES

DR MILES RUSSELL is an expert in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquities and one of only a handful of people to have excavated at Stonehenge.

Stonehenge hasn’t given up its secrets easily. What it was for and how it was built are just two of the questions that have been vexing archaeologists

DID

YOU KNOW?

There are many henges in Britain, but you can’t count Stonehenge among them. The term describes a raised earthwork with an internal ditch; Stonehenge’s ditch is outside its earthwork, meaning it isn’t a true henge. Avebury, several miles to the north, is probably the most famous real henge.

One hundred years ago this year, Stonehenge came into public ownership. After many centuries of neglect, damage and wilful vandalism, the monument could at last be protected for future generations to enjoy. While state ownership brought with it limitations on access and the imposition of an entrance fee, it also ushered in a period of organised investigation and controlled conservation.

Standing proud on Salisbury Plain in southern England, Stonehenge is one of the most iconic monuments in the world. Well over a million people visit the site every year and numbers are on the rise, especially since the opening of a new visitor centre. Yet very little is really known about the structure; a complete absence of written material means that we can only speculate about its creation and significance. As a result, Stonehenge has been a constant source of conjecture, from the earliest recorded tourists to the present-day archaeologists and academics who work there.

The site, as we see it, comprises a confusing jumble of stone uprights, some capped with lintels, together with their fallen compatriots, all set within a low, circular earthwork.

You can’t enter the stone circle during normal opening hours (that’s only possible on special tours), so for most visitors the site is visible only from afar: tantalising, enigmatic and out of reach.

Damaged and distant though it undoubtedly is, Stonehenge remains awe inspiring, especially when one considers it was put together 4,500 years ago by a pre-industrial farming society using tools made of bone and stone.

Ten years ago, I was fortunate enough to be part of a team excavating within the central uprights of Stonehenge in the first archaeological investigation there for 70 years. Led by professors Tim Darvill and Geo Wainwright, the dig felt at the same time exciting and curiously sacrilegious. It was as if by removing the turf from this hallowed monument, we were in some way committing an act of desecration.

The many thousands of tourists who saw us were keen to touch the freshly excavated soil and ask questions about when the site was constructed, who built it, why was it here and, most importantly of all, what did it all mean? After nearly 400 years of archaeological examination at Stonehenge, that last question is perhaps the most difficult to answer.

Professors Tim Darvill and Geo Wainwright begin their dig in 2008

DID

YOU KNOW?

The earliest depiction of Stonehenge appears in the Scala Mundi (Chronicle of the World), compiled around 1340. The monument is drawn rather unrealistically, appearing rectangular (rather than circular) in plan.

“VERY LITTLE IS KNOW ABOUT STONEHENGE; WE

CAN ONLY SPECULATE ABOUT ITS SIGNIFICANCE ”

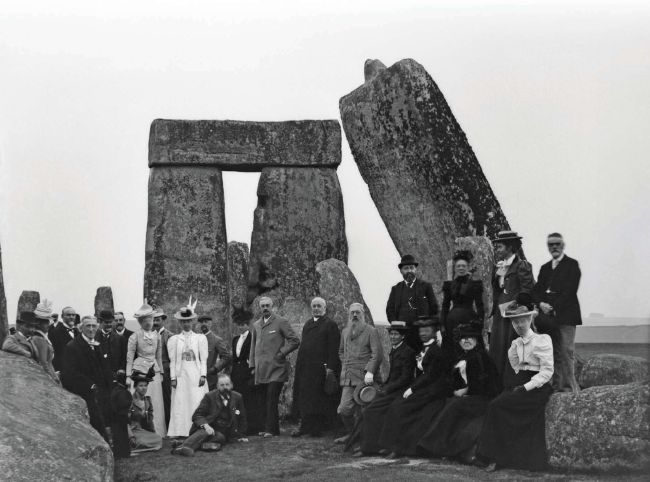

Victorian tourists flocked to Stonehenge, just as we do today – though they were permitted to picnic beneath the trilithons

DIGGING FOR TRUTH

The first attempt to resolve the date of Stonehenge occurred in the 1620s during an excavation commissioned by the Duke of Buckingham. Unfortunately we know little about the work, other than it exposed at least two large pits, together with “stagges hornes and bulls hornes” and “pieces of armour eaten out with rust”. None of these finds survive. Further exploration took place in the early 19th century, work which may have contributed to the overall instability of the stones. On New Year’s Eve 1900, part of the outer circle of sarsen stones collapsed, taking down a lintel with it.