RAILWAYS ABROAD

By rail to sea!

Tom Ingall tells the extraordinary tale of how Florida’s Key West became one of the world’s most unlikely railroad termini.

YOUR case is packed and you are Florida bound. For many, particularly families, ‘The Sunshine State’ is the ultimate holiday aspiration. They are doubtless lured by the sprawling campus of four Walt Disney theme parks, created from swampland just south of Orlando, where in 2019 just shy of 60 million people visited them. While the visionary creator died before he saw the project open in 1972, his legacy is an unprecedented global tourism machine.

But I would argue that Disney is not the father of Florida as a destination. If anyone deserves that title, industrialist and entrepreneur Henry Flagler must be in contention. Without him, the great East Coast resorts of Daytona Beach, Palm Beach and even Miami would not exist as they do today. The latter city would even bear his name were it not for his modesty, but you will find him commemorated on streets and businesses the entire length of the Atlantic Coast, his contribution to shaping modern Florida celebrated over hundreds of miles.

Flagler became a very rich man after co-founding the Standard Oil Company (part of which survives today as ExxonMobil) with John D Rockefeller in 1870. This article could never hope to be a biography, but very broadly his life story can be divided in two. The first half sees him build a business empire, while facing accusations of sharp practice and fighting political opposition. But he was undoubtedly savvy and driven, with even Rockefeller crediting Flagler as the brains behind Standard Oil.

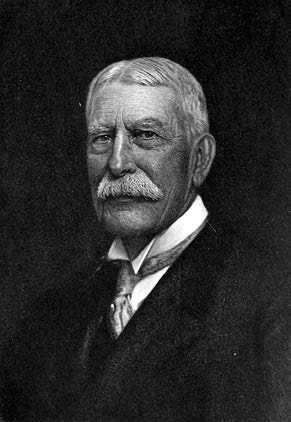

A portrait of industrialist Henry Morrison Flagler (January 2, 1830 to May 20, 1913).

In 1877, however, his first wife’s illness put his life on a new path. On doctor’s orders, he and his family travelled from their home in New York to Jacksonville (at the northern tip of Florida), where for the first time he experienced the warm climate and a reprieve from his business-driven life. After his wife’s death, Florida became the stage on which the second act of his life was played. Other wealthy people followed his path to the emerging state, and their patronage was key. Flagler built hotels to accommodate them, buying out, extending and developing existing railroads to transport the visitors. He extended lines through undeveloped land and, wherever he went, development followed. To mangle a phrase, the rest is geography.

The Florida East Coast (FEC) railroad network was the line on the map everyone followed. He was not immediately interested in extending south of Palm Beach, believing he had found his natural terminus, but the weather would change his mind. A deep freeze in 1894 blighted the area causing hardship to locals. The myth runs that the founders of a small settlement 60-odd miles to the south sent Flagler a bouquet of orange blossom to show they were unaffected by the cold. More likely, they made him a land offer he could not refuse. And so by 1896, the first trains were arriving in what would go onto be known as Miami, a city the entrepreneur invested heavily in, and it was he who suggested the native American name would be most appropriate for the new metropolis.

Folly or wonder

By now in his mid-60s, Flagler’s greatest adventure – his ‘folly’, or ‘the eighth wonder of the world’, depending on your point of view – was still ahead.

The Florida Keys are a string of islands spilling out to the south-west from the bottom of the state. Some are just a few metres wide, others more substantial. At the far of the end of the chain is the city of Key West, an isolated outpost that was once Florida’s largest and wealthiest city. Its trade was built on fishing, wrecking (a highly aggressive form of maritime salvage) and cigar making. Militarily, it was a significant outpost, commanding a point in the sea between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. It is also only 90 miles to Havana, thus much closer to Cuba than Miami.