Eye Of The Survivor

Jon Anderson isn’t the only person who wishes 2020 had panned out a little differently, so he’s cranked up the time machine and jumped back to 1980 with the reissue of his second solo album. Released after his initial departure from Yes, Song Of Seven was the second step in a long and successful solo career that’s seen the singer-songwriter collaborating with Vangelis, Mike Oldfield and his old Yes bandmate, Rick Wakeman. Prog catches up with Anderson to revisit the making of Song Of Seven and found out how he survived one of prog’s most challenging decades.

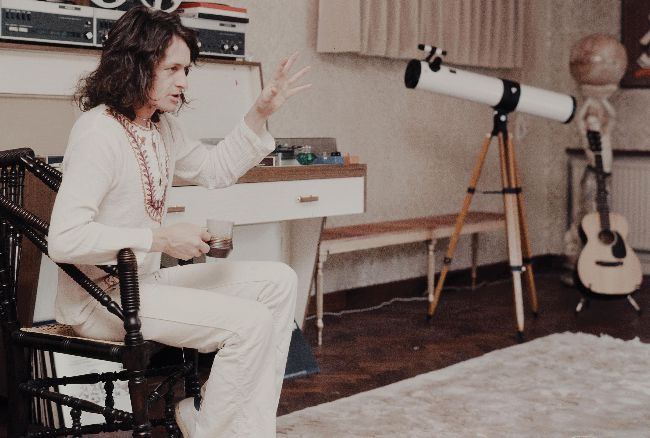

Words: Sid Smith Portrait: Koh Hasebe/Shinko Music/Getty Images

All white on the night: Jon Anderson in the 70s.

“For me, I am Yes. It’s never left me.”

I’ve had it with your sweettalking politicians, all you want to do is go and steal the world, try to tell us that you’re here for all the people, when inside you’re really out to screw us all,” says Jon Anderson with some gusto. He’s reciting the lyrics from Go Screw Yourself, a song that would be released online a few days after Prog’s interview. His anger at the current political situation is palpable. As he talks, his words are interspersed with rueful, heavy sighs at what he sees as the terminal stupidity and wilful deceit of a political class lining its own pockets at the expense of people and the planet. “They’re like children playing around: ‘It’s my ball. No, it’s my ball.’ That’s all it is. These politicians drive me crazy because they’ve no sense of compassion or what’s really going on. It’s about time we all woke up, seriously.”

The smoke-filled skies above his California home and elsewhere that have dominated his home state following this year’s spate of forest fires only adds fuel to Anderson’s ire and exasperation. “The most important thing at this time in our world is Mother Earth and saving it for our children’s children,” he says. “There’s a bigger world out there there’s got to be taken care of rather than greedy politicians playing ‘who’s got the ball.’”

Faced with the daily doom and gloom of newspaper headlines, Anderson nevertheless remains optimistic about the possibility of a substantial shift in public opinion. At his core, e believes that good will prevail, that despite the travails and challenges, what’s best of us will survive. Anderson is nothing if not a survivor. “I always have a very positive feeling about the development of a state of mind and the consciousness of the planet, by which I mean everybody is going to raise their consciousness after this terrible virus,” he says referencing the implacable rise of Covid-19, fully aware that as a chronic asthmatic, a condition that nearly killed him in 2008, he’s especially vulnerable. “They’re going wake up a bit and realise that looking after the planet, looking after this beautiful home of ours is what we should be doing.”

Yes onstage at Ahoy, Rotterdam, Netherlands, on November 24, 1977. L-R: Jon Anderson, Steve Howe, Alan White, Chris Squire and Rick Wakeman.

ROB VERHORST/REDFERNS/GETTY IMAGES

The notion that a song could help crystallise a thought into a popular cause or movement may seem fanciful to some but to Anderson, it’s a given. “One song will come along and people will hear it and say, ‘Shit! That’s correct, these people have got to wake up and dream rather than wake up and look for money.’ John Lennon said it: ‘Make love not war, give peace a chance.’”

This isn’t the first time Anderson has invoked Lennon’s anti-war/procompassion message either. In 1971, the rousing chorus of Give Peace A Chance was discretely co-opted into the backing of I’ve Seen All Good People from The Yes Album.

Although the views expressed in Go Screw Yourself are explicitly unambiguous, Anderson’s form in that department hasn’t always been so crystal clear. Over the decades the precise meaning of much of his work has been famously obscure and oblique, usually resisting the usual kinds of literary and literal analysis from sceptical critics and hardcore fans alike. Nevertheless, Anderson insists that the mundane, worldly realities of current affairs have always found their way into his music, a subtle influence that has on occasion directly inspired a lyrical approach. A case in point, he argues, would be elements of For You For Me from Song Of Seven, originally released in 1980 and, now in 2020 it’s the subject of a remastered and expanded reissue. “I was actually listening to it last week just to check on what I was thinking in those days, and it’s pretty political, it’s an interesting song,” he says enthusiastically.