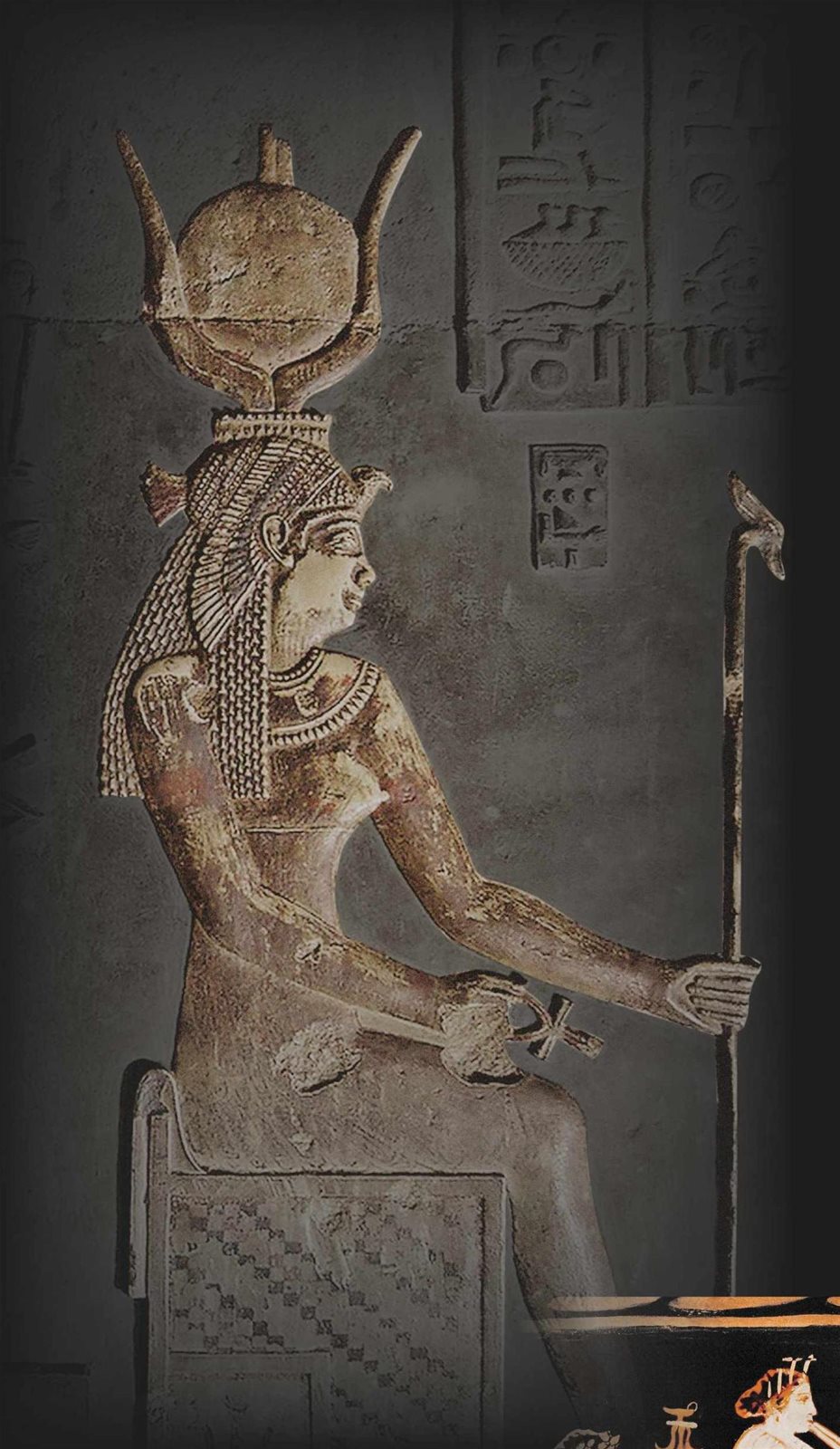

Fading force

A bust of Ptolemy XII (left), and (right) his daughter Cleopatra VII. Ptolemy’s attempts to ingratiate himself with Rome’s powerbrokers spelled trouble for ancient Egypt’s final royal dynasty

BRIDGEMAN/AKG/GETTY IMAGES

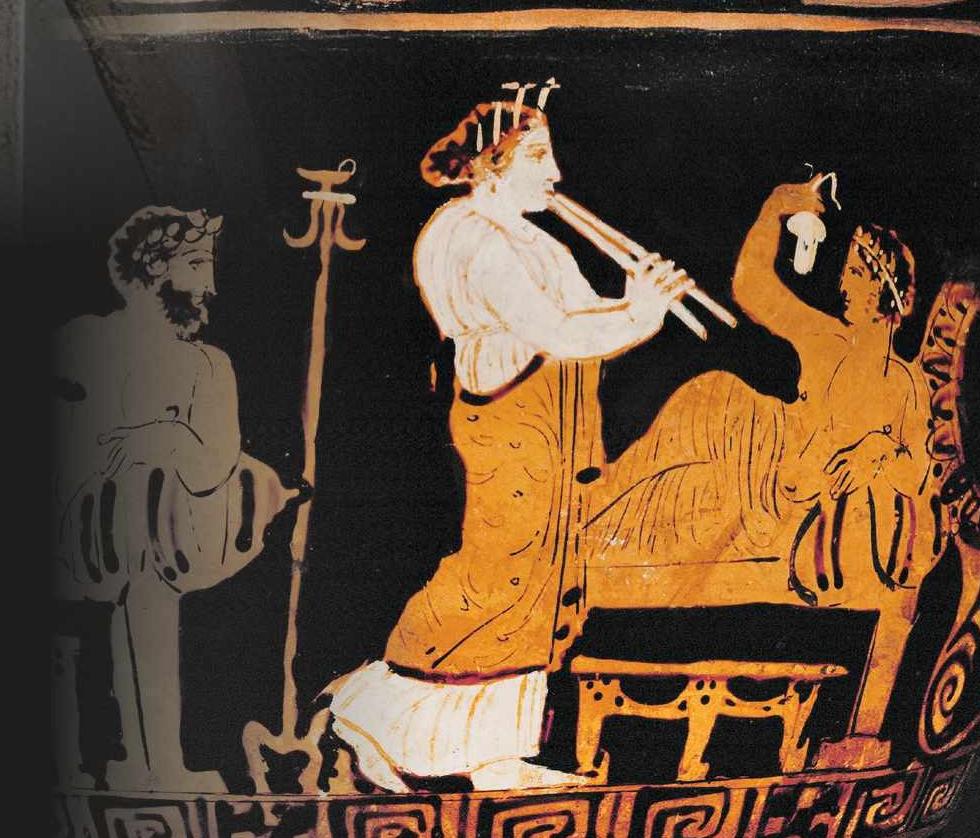

Royal raver

A woman plays the flute in an ancient Greek vase painting. Ptolemy XII’s penchant for live music earned him the nickname

‘Auletes’ or ‘flute player’

It’s one of the most famous episodes in all of ancient history. Cleopatra VII, Egypt’s formidable queen, ends her life and creates a legend. Following the suicide of her lover, Mark Antony – and with Octavian’s armies closing in – she concludes she has nothing more to give and succumbs to the poison.

For all the drama surrounding her final moments, Cleopatra’s demise was, in reality, an ignominious one. When she killed herself in 30 BC, Egypt was in dire economic straits, its wealth pillaged, its people shocked and confused. The future of this once extraordinarily powerful kingdom lay in subjugation.

So how had it come to this? How did Egypt, with all its material riches and even richer cultural heritage, arrive at a point where it was subsumed into the Roman empire? One answer to these questions lies in the legacy of Cleopatra’s father, Ptolemy XII, a man who sought to shore up his position by funnelling funds to Rome’s politicians, but in so doing bankrupted his country and alienated his own elite.

Ptolemy is not a man who comes down through the years with much credit. The Greek geographer, philosopher and historian Strabo, writing in Geographica, dismissed Ptolemy as one of the worst of the dozen Egyptian rulers to bear this name. Not only did Ptolemy descend from a line “corrupted by luxurious living” but he was a man of “general licentiousness”. A telling detail is that Ptolemy’s nickname, ‘Auletes’, literally meant ‘flute player’ and reflected his eccentric habit of joining the musicians in Dionysian revels. The philosopher and lawyer Cicero was equally damning in his pithy assessment, dismissing Ptolemy as a man lacking “any royal disposition”. in swathes of south-east Europe, western Asia and north Africa. The great empire-builder’s sudden demise was an Earth-shattering event, and it triggered four decades of war as his generals fought one another for control of his vast territories.

Egypt, as one of the jewels in Alexander’s crown, found itself sucked into the spiral of conflict – and, when the dust finally settled, one man was left standing: a Macedonian Greek called Ptolemy Lagus (pictured below). He had already earned himself a place in history by intercepting Alexander’s funerary cortège as it made its way across the Syrian desert and ordering his burial in the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis.

Then, in 305/304 BC, he made history once again by having himself crowned king of Egypt.

Ptolemy’s coronation – as Ptolemy I Soter (the Saviour) – was a true turning point in the story of Egypt, for he was the founder of the ancient kingdom’s last dynasty, one that would endure until Cleopatra’s suicide 275 years later.