DREAMSTIME

In November 1590, a servant named Geillis Duncan from East Lothian was interrogated by her employer, David Seton. According to Newes from Scotland, a 1591 pamphlet that included a report of the case, Geillis used to sneak out of her master’s house at night. She also “took in hand to help all such as were troubled or grieved with any kind of sickness or infirmity” and performed “many matters most miraculous”.

Suspicions aroused, Seton questioned Duncan about how she worked her cures. When she gave no answer, he tortured her with thumbscrews and by “binding or wrenching her head with a cord or rope”. Still she remained silent. Finally, Seton and others searched her for a ‘devil’s mark’ – a blemish or insensitive spot created by Satan – and found one on her throat. She broke down and confessed “that all her doings were done by the wicked allurements and enticements of the devil, and that she did them by witchcraft”.

Witchcraft had been criminalised in 1563, and there had been a handful of prosecutions since. But Duncan’s confession kicked off something new – Scotland’s first large-scale witch-hunt. What’s striking about this panic over supposed black magic is just how much more intense and lethal it was than witch-hunting in other European countries – perhaps most notably England.

Following her interrogation (involving torture), Geillis Duncan claimed to have participated in a night-time witches’ gathering, also known as a sabbat, at North Berwick kirk. She alleged that other locals were present, and as many as 70 people were ultimately accused. Their confessions detailed bizarre and alarming practices. Supposedly they had sailed across the sea in sieves, meeting at the kirk to dance and sing. The devil had preached from the pulpit, and they had kissed his buttocks. Some of the accused also claimed to have attacked King James VI, casting spells to harm him or raising storms to sink his ships.

Newes from Scotland reported that the devil considered James VI “the greatest enemy he hath in the world” – a statement designed to flatter a monarch who believed himself divinely appointed. But James was also fearful of the devil’s designs on him, and involved himself directly in the interrogation of the accused witches. Blame began to make its way up the social scale, and the king’s own cousin, the Earl of Bothwell, was accused of heading a conspiracy against the monarch. Although he was eventually acquitted, Bothwell’s political career was ruined, and he was forced into exile.

The last executions resulting from the North Berwick trials were in 1592, but the fallout from the witch-hunt endured far longer. The idea of the threat of witchcraft had been promulgated from the highest social echelons, and was further publicised in 1597 when James VI published Daemonologie, a book about the devil’s wiles.

Mass witch-hunts swept Scotland again in 1628–30, 1649 and 1661–62. The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft, a database recording known prosecutions, has identified 3,837 accused. Execution rates are difficult to establish but may have been in the region of two-thirds. By these metrics, Scotland’s execution rate per head of population may have been about five times the European average, and 10 times that in England.

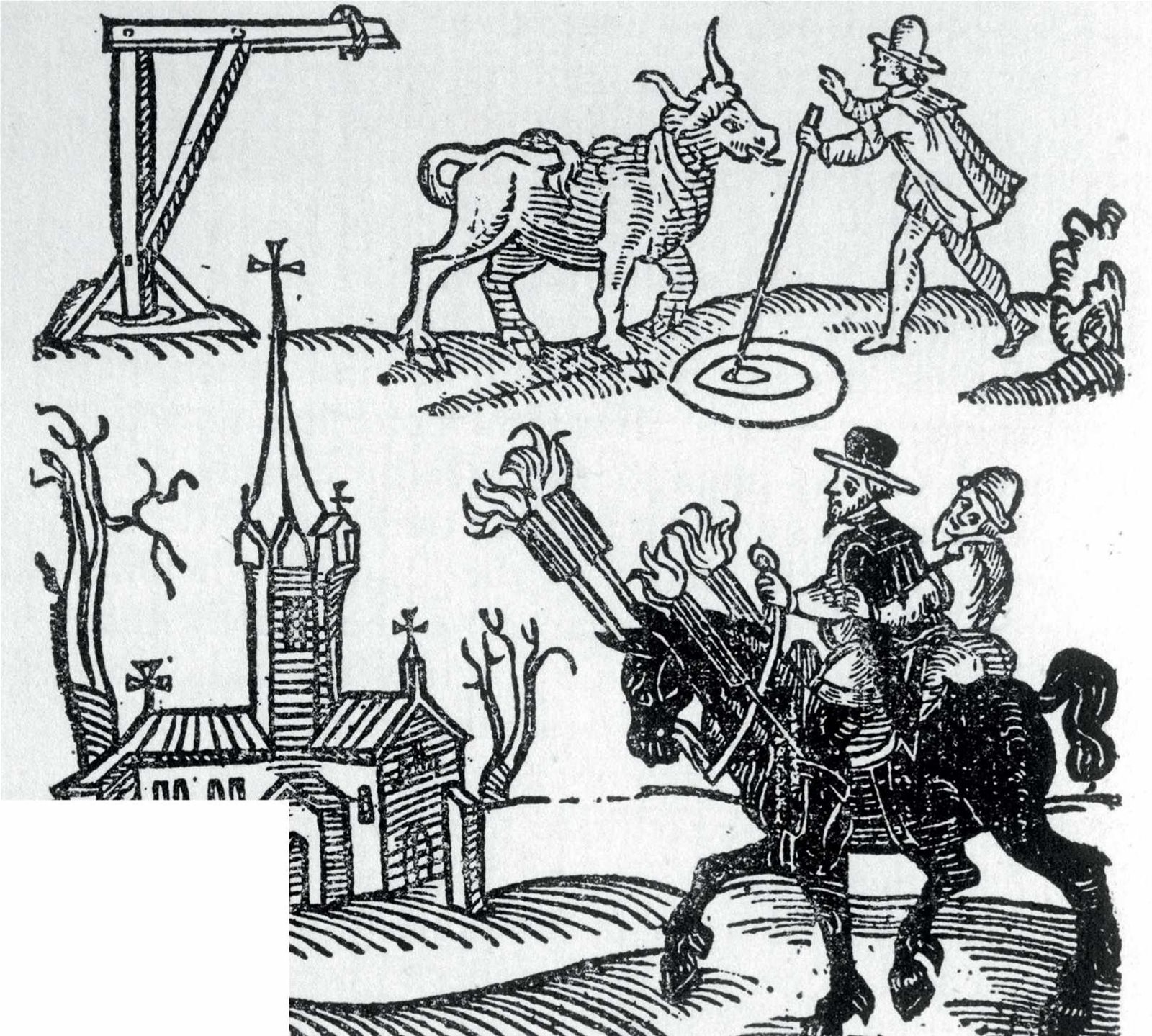

Burning injustice A woodcut in Newes from Scotland (1591), a pamphlet reporting the North Berwick witch trials, depicts John Fian enchanting a cow and adding torches to his horse’s ears

ALAMY/DREAMSTIME