RAIDERS TO KINGS What began as small raids on British coastal towns soon developed into all-out war, as a Great Viking Army arrived with a very different aim: to conquer

ILLUSTRATION: JEAN-MICHEL GIRARD/WWW.THE-ART-AGENCY.CO.UK, ALAMY X1

This year marks the millenary of the acclamation of a prince of Denmark as king of England. The victor of a long and bloody campaign, marrying the widow of his conquered predecessor, Cnut stepped up to the controls of one of the most powerful kingdoms in 11th-century Europe. Remembered in Denmark and much of Scandinavia, but curiously not in England, as Knud den Store – ‘Cnut the Great’ – the new Anglo-Danish King would wield power effectively for some two decades until his death in 1035.

Cnut’s transformation from Viking sea lord to Christian king is a perfect example of the way in which the Vikings themselves had changed. The journey from seasonal raiders and pirates to highly respected rulers had taken a little over two centuries, but it was one of the most important developments in Western Europe. Not only had Denmark, Norway, Iceland and Sweden come of age, but the English and Scottish kingdoms had emerged in the white heat of the Viking wars.

SLOW START

In Britain and Ireland, the age of Norsemen had begun gradually. The first Viking activities were surprisingly small, but they were deadly and had an impact far beyond their size. Flotillas made their way across the North Sea to raid coastal and estuarine sites, particularly monasteries, chocked full of treasures as a result of an eighth-century economic boom. Those who embarked on the raids were the happy beneficiaries of developments in maritime technology, which allowed them to set out from Scandinavia confident of being able to return safely again. Though, like other ships of the age, they could be rowed, Viking ships enjoyed beautifully rigged square sails; they had strong keels and well-designed hulls. It has even been argued that Vikings had developed their navigation skills well in advance of other European peoples. While many early medieval ships used coastal routes to travel between lands, the new longships could dominate sea roads across open water, perhaps even as early as the 780s and 790s. Writing of the earliest datable Viking raid on the famous monastery of Lindisfarne in June 793, one churchman wrote of surprise “that such an inroad from the sea could be made.”

This ninth-century grave marker found That Lindisfarne depicts Vikings brandishing swords and axes

The writer was Alcuin, formerly a deacon of York Minster, who had risen to become Charlemagne’s right-hand man. Although he was some 500 miles away in the court of Charlemagne, Alcuin conveys some of the sense of the shock of hearing the news of pagan raiders’ actions. To many Christians, the Vikings heralded the apocalypse. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a year-by-year record of events associated with the kingdom of Wessex, reported that the Vikings’ arrival was preceded by freak atmospheric conditions – “dragons” were seen flying across the sky – and indeed one gravestone found That Lindisfarne (above) shows heathen barbarians in apocalyptic terms: the Sun and the Moon, portents of the End of Days when the Sun would turn to darkness and the Moon turn a blood red, are juxtaposed by an image of seven warriors, most of whom brandish surprisingly realistic contemporary weapons. Whoever buried that member of the Lindisfarne community evidently thought that a message had been sent and had to be heeded.

WHO WERE THE VIKINGS?

When scholars write about Vikings, they often refer to groups of people from the Scandinavian lands of Norway, Sweden and Denmark. While much of Europe was Christian by the eighth century, these areas were not.

However, not everyone went ‘Viking’ – many continued to farm the land or might return to farming after a few years of raiding, while others such as Anglo-Saxons and Franks might also ‘go Viking’. This was not about belonging to a ‘race’ or even a religion. Being a Viking was an activity.

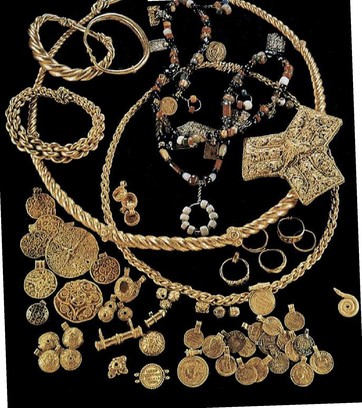

The Vikings were notorious for plundering gold and jewels

This became possible because of the development of ship technology, and it was encouraged by the growing strength of Scandinavian chieftains. What better way to enhance a reputation than by taking followers on raids to acquire greater riches? This rather dodgy redistribution of wealth stimulated an international exchange network, meaning that a living could be made by mixing trading and raiding. Vikings might be raiders one day and then sell their ill-gotten gains elsewhere the next.

In these early raids, it was speed and surprise that brought success. Where Vikings are known to have faced opposition, such as down the coast from Lindisfarne, perhaps after a raid on the monastery That Jarrow in 794, local forces could match them effectively. Anglo-Saxon kingdoms themselves had their own share of hardened warriors, whose whole lifestyle was organised towards the defeat of their enemies, and so they were no pushover. But with armies organised for battles fought according to rituals and expectations (at particular places and perhaps even at particular times of the year), they were rarely able to catch more mobile enemies. As one historian aptly put it, the Vikings did not “play by the rules”.