ON THE RIGHT TRACK

Dumped by Island, pushing 50,TOM WAITS responded with some of his greatest ever music. OnMule Variations, Alice and Blood Money, the stage and the studio, Weimar and the Old, Weird America intermingled in a soundworld that was uniquely Waits. "The last thing he wanted was anything normal," his confederates tell SYLVIE SIMMONS.

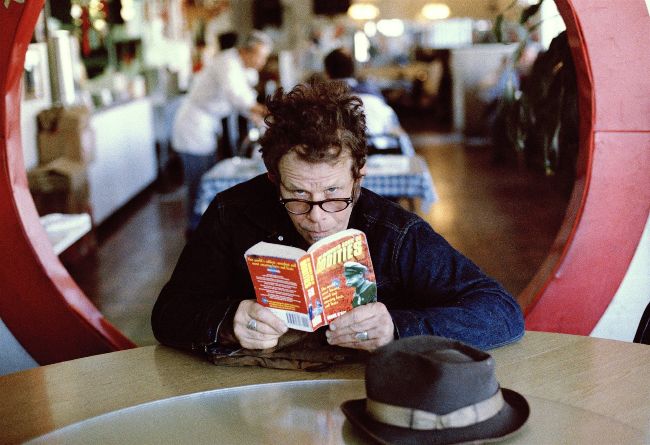

"OH YEAH, IT WAS MY first record for them and I had no idea what was going to happen. I was excited, it was a brand new record label so it was really a chance to have a debut.” A waitress comes over with a coffee jug in each hand for a third re-fill – Tom Waits takes his black, and decaffeinated: “I go crazy if I drink the real shit.” Returning to the sto-ry, “I wasn’t really sure,” he said, “where I fitted in with everybody else, but they convinced me that I belonged there and that gave me confidence, you know? At that time it was really almost exclusively a punk label. Here I am, almost 50. Am I some old fuddy-duddy trying out a new haircut?”

Shortly before the end of the 20th century, Tom Waits signed to Anti-Records – part of Bad Religion guitarist Brett Gurewitz’s Epi-taph empire – sealing the deal with label head Andy Kaulkin with a handshake over coffee at a truck stop. Anti- was Waits’s third re-cord label. He started out in 1973 on Asylum Records. Ten years later he moved to Island, after Asylum rejected his album Swordfis-htrombones (1983) on the grounds that it would scare the horses and alienate his fans – words that were proof enough to Island boss Chris Blackwell that Waits belonged on his label. As Blackwell wrote in his memoir, “If you look at the artists we worked with, it all led to Tom Waits.”

Waits’s 10 years and five albums on Island were remarkable, a period when he changed direction, changed his music, changed his address, his life, everything. His new songs, co-written with Kathleen Brennan, his wife since 1980, were savage children let loose in a surreal musical landscape of carnivals, cabarets, nursery rhymes, abandoned car lots, fairy tales (Grimm) and Salvation Army bands – all of this with his new label’s blessing. That The Black Rider (1993) – the first of Waits’s collaborations with avant-garde theatre direc-tor Robert Wilson – would turn out to be his last album on Island had nothing to do with Blackwell’s disapproval; Blackwell was no longer in control. The big fish in the music business were eating the smaller fish and Is-land had been bought by Polygram. And what Polygram wanted were hits.

So Tom Waits signed with an even smaller fish. In 1999 he released Mule Varia-tions – his first album in six years and Anti-’s first album ever. And wouldn’t you know it, it was a hit.

People get ready: Tom Waits enjoys the taste of freedom, Santa Rosa, California, January 1999.

Photograph: JILL FURMANOVSKY

Anti- nature: (this page, from top) read all about it – Tom Waits at the bar, Santa Rosa, 1991;

Jill Furmanovsky

MULE VARIATIONS WAS THE FIRST TOM Waits album to make the US Top 30. It went platinum. It was MOJO’s Album Of The Year. It won the Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album. The 16 songs included work songs, church songs, civil war songs, chain gang chants, murder ballads and a lot of blues. Bluesmen John Hammond Jr and Charlie Musselwhite were among the roster of musicians that also included old faithfuls like Marc Ribot, Ralph Carney, Ste-phen Hodges and Larry Taylor.

“All that Alan Lomax stuff coming out on Smithsonian, it changed the lexicon, the whole cul-ture,” Waits told me some years ago. “Before that, that stuff was only available for academic research; now you can buy all those field recordings from a re-cord store. Incredible! When [Lomax] first went out, his tape recorder weighed 500lbs and most of the people, when he said he wanted to record them, looked at him [askance] like the RCA dog, like, ‘What?’ It was like someone coming to your house and telling you, ‘I want to take all your pictures that your kids did on the refrigerator and put them in a book.’ ‘What are you talking about?’”

The true beauty of those field recordings for Waits was that “they were made completely unself-consciously. It wasn’t like a band that knew who their audience was. There was a real sweetness to it, because they were singing into a device that they’d never seen before and they didn’t know who they were singing to.”

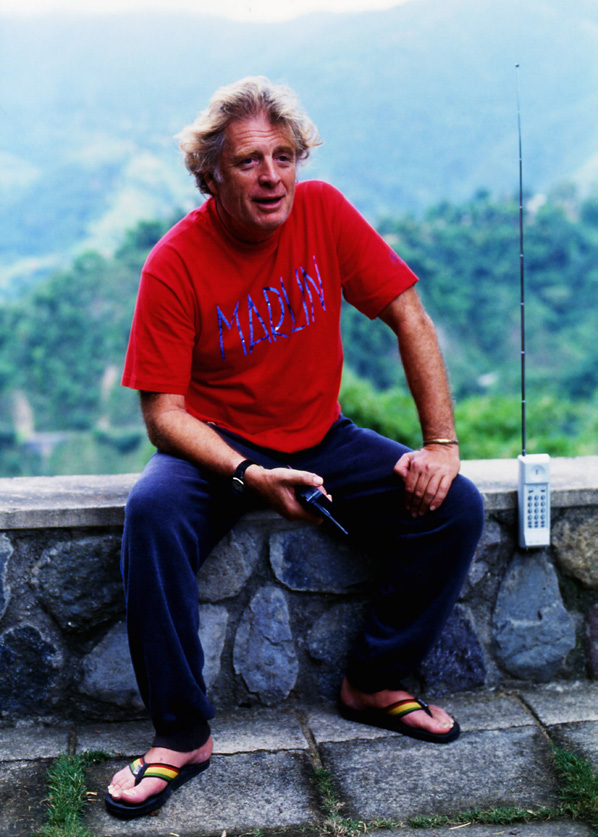

erstwhile Island boss Chris Blackwell, Jamaica, 1993;