THE MOJO INTERVIEW

Transcending grunge, Pearl Jam’s brooding baritone has fought his demons, the ticket agents, and his President. Today, he takes each day as a challenge to his devotion to “all that’s sacred”. “ The bar keeps rising,” insists Eddie Vedder.

Interview by KEITH CAMERON

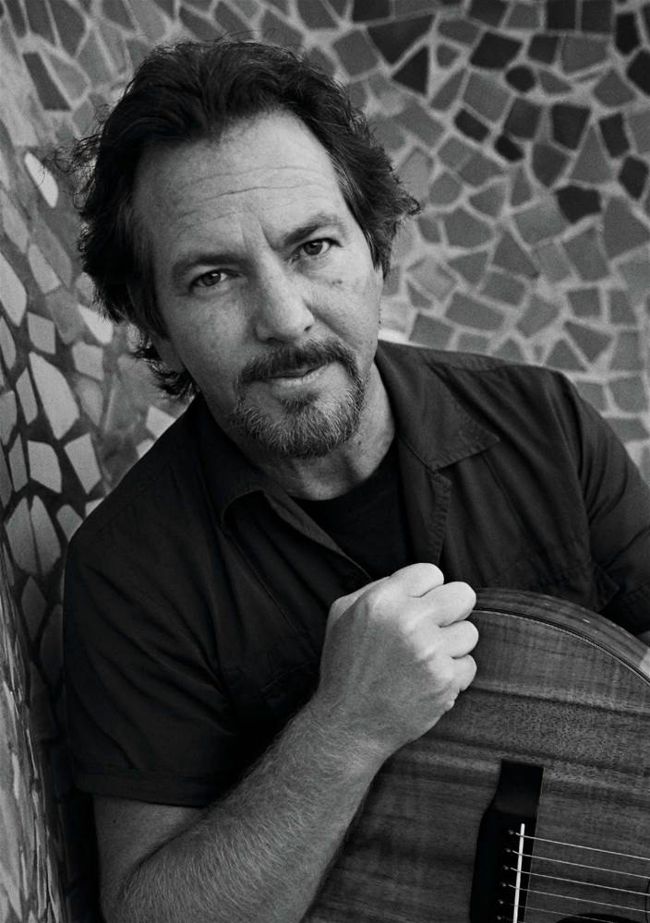

Portrait by DANNY CLINCH

“ONE SECOND…”

Eddie Vedder gets up mid-question, leaving us with an unimpeded view of the music room in his Seattle home: a few amplifiers, a piano, the walls hung with photographs, presentation discs and some guitars. After a few moments’ off-screen clinking, Eddie reappears with a Corona, levering the top off with his cigarette lighter. “I’ll join you!” he beams, raising his bottle to MOJO’s pint glass, 5,000 miles away.

Two weeks short of his 57th birthday, Vedder is the ver y model of the middle-aged mixed-up kid, with the beer and smokes in the afternoon, his jacket/shorts/baseball cap/Who T-shirt ensemble detailed with a PiL pin. During early summer, he began recording

Earthling, his third solo album, with Andrew Watt, the Grammywinning producer of Justin Bieber and Miley Cyrus. In late September, he premiered two of WE’RE NOT WORTHY its songs at Ohana, the festival he’s curated at California’s Doheny State Beach since 2016. his Ohana also saw Pearl Jam’s return to live action, their first run of shows since a scheduled 2020 tour in support of their eleventh album Gigaton became an early casualty of the Covid pandemic.

“Been travelling a lot,” Eddie nods. “We played the new record for some people over the weekend, the first time in a while I’ve travelled without carr ying 50lbs of books and papers and lyrics. Some of the lyrical content is heavy too, so I was wondering if that added to the weight of the bag.”

Vedder is no stranger to heavy. Born Edward Severson in the Chicago suburbs, then relocated to San Diego as a preteen, he was four months old when his parents divorced, and grew up believing his stepfather to be his father and his biological father a family friend. Upon learning the truth at 17, he took his mother’s maiden name. This thorny origin stor y became the basis for Alive, the first song Vedder wrote for the nascent Pearl Jam in October 1990, after his drummer friend Jack Irons had recommended him to Seattle proto-gr unge scene alumni Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard, whose band Mother Love Bone had ended when singer Andrew Wood died of a heroin overdose.

So began a 30-year odyssey, which saw Pearl Jam catapult to fame on the back of 1991 debut album Ten’s stew of trad rock grandiloquence and Gen-X angst, plus a relentless touring ethic and MTV ubiquity. The weight sat unhappily with Vedder, a shy man hiding inside a dramatic baritone, but even as 1993’s Vs sold a scarcely fathomable 950,000 copies in its first week, he was plotting a withdrawal. Pearl Jam made no more videos, gave no inter views, kicked back against Ticketmaster, and reconfigured their music toward an ascetic hardcore mysticism, reducing sales yet nourishing a sense of collective integrity, while also stoking a devoted fanbase via officially sanctioned bootlegs of their legendarily epic shows. These deep bonds saw them through the trauma of 2000’s Roskilde Festival, when nine fans died in a crush during Pearl Jam’s set.

Today’s Eddie Vedder has found a happy accommodation between his private and public selves, a dude who can call Bruce Springsteen and Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye friends, as comfortable hanging with the Cosmic Psychos as Barack Obama. “All that’s sacred comes from youth,” he sang in Pearl Jam’s 1994 song Not For You, a punked update of the teenage Vedder’s first love, The Who, and an imperative he’s upheld throughout. “Certainly,” he chuckles, “if there’s more than one life, this has got to be the best one.”