“We weren’t trying to make a pop song, that’s for sure”

As follow-up to the divisive Tales From Topographic Oceans, Relayer was never going to be an easy record to make. Crafted shortly after Rick Wakeman’s departure, it marked a more modern sound for Yes and became the band’s only studio album to include Swiss keyboardist Patrick Moraz. Prog steps back 50 years to uncover the story of the album that could have featured Vangelis.

Sound Chaser: Sid Smith

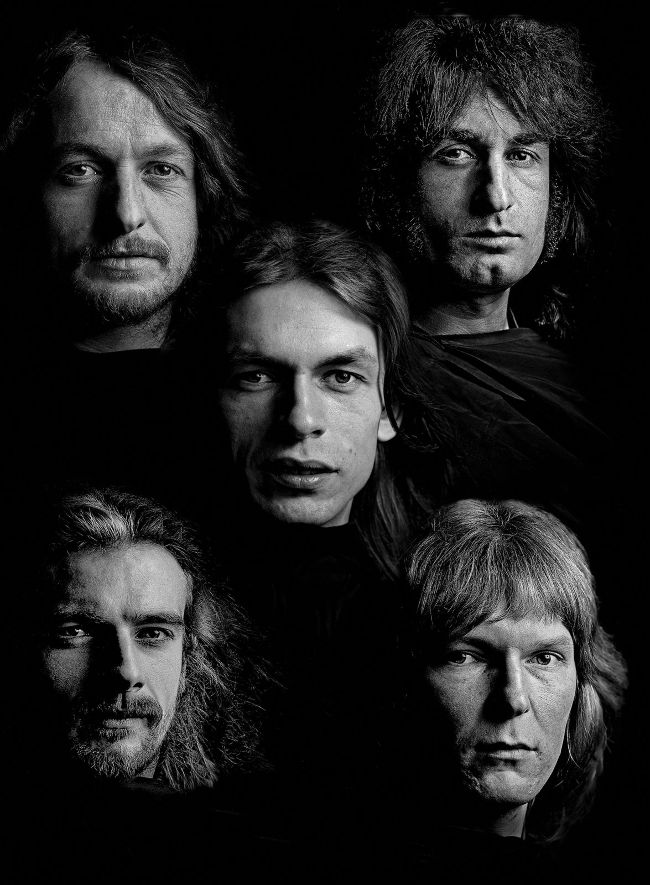

Yes circa

Relayer,

at their most experimental.

Portrait :

Clive Arrowsmith/Camera Press

J on Anderson is looking back on events that happened 50 years ago when, as a 30-yearold man, he was fronting one of the most commercially successful bands of the time. He laughs incredulously as some of those memories come to the fore.

“There’s a brilliant photograph somewhere where we’re all holding the faders on the mixing console, and everybody’s got hold of their own lever. That’s the perfect picture of what the band was like at that time. Everybody wants to do their best, but everybody’s on top of each other and not quite knowing what’s next. It’s a funny photograph but it actually depicted where we were and musically; we were all just trying to do some really good stuff.”

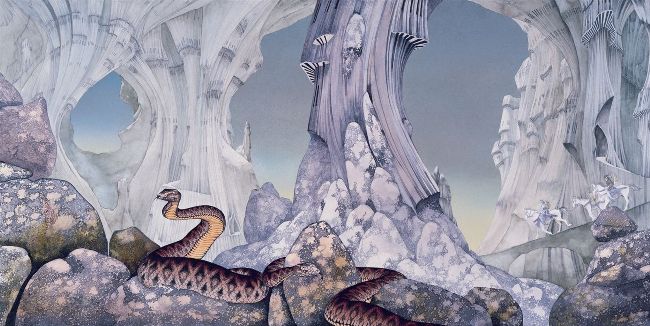

Roger Dean’s

The Gates Of Delirium

illustration for

Relayer.

PAINTING AND LOGOS © ROGER DEAN 1974

The Turkish-American electronic music composer İlhan Mimaroğ lu once said, “Music is a cinematographic concept. A type of cinema that is observed by the ear.” That description easily applies to the remarkable body of music Yes generated from the early 70s onwards. The Yes Album, Fragile and Close To The Edge honed and refined a compositional style that created pictures in the mind, enhanced as they were by high-value productions. But if these albums exemplified a keenness to explore that cinematic approach, in the scale of its ambition Tales From Topographic Oceans was something akin to an aural IMAX screening.

Close To The Edge

had launched Yes on their way as a significant international force, but, by comparison,

Tales…

was a more considered and introverted work. When performed

in its 80-minute entirety on those tours of Europe and North America during ’73 and ’74, it wasn’t always well received by some sections of the audience. Some critics struggled to assimilate and digest this somewhat intricate and seemingly wilfully obscure successor, garnering a clutch of negative reviews from a music press that had largely supported the band’s work in the past. Yet such was their momentum,

Tales From Topographic Oceans

gifted Yes their first No.1 LP on the UK charts over the Christmas of 1973, and sailed into the American charts at a highly respectable No.6.

“They’re all scratching their heads, saying, ‘Why are we doing this?’ But it was very exciting. I was very happy when they decided to take it on.”

Jon Anderson

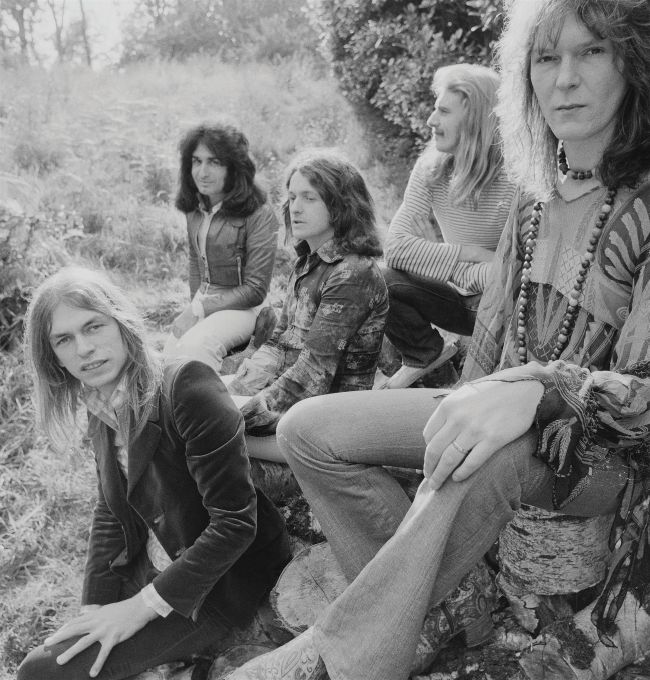

Yes on September 19, 1974, L-R: Steve Howe, Patrick Moraz, Jon Anderson, Alan White and Chris Squire.

VAN HOUTEN/DALLE/ICONICPIX

“That’s what makes Yes so unique; everything is encompassed in the arrangement and every note is absolutely critical.”

Patrick Moraz

The album came at a price, though. Rick Wakeman, who had done so much to galvanise and focus Yes’s work as a writing body, was feeling semi-detached and distracted by an increasingly lucrative solo career following The Six Wives Of Henry VIII’s release in January 1973. The Topographic tour only served to highlight the gulf that had opened up in the band’s lifestyles with Wakeman firmly on the booze-andlaffs side of things and the rest digging into their spliffed-up macrobiotics and spirituality on the other. Perhaps more importantly though, the touring only cemented his view that the material on Tales… was padded and lacked in substance. When Wakeman heard the pieces that were emerging for their next recording, infused as they were with a jazz-rockish sensibility, the signs did not bode well for his continued tenure.

Yes were no stranger to bandmembers leaving the fold. Steve Howe had come in after Peter Banks had been sacked in 1970 and Wakeman himself replaced Tony Kaye following the release of The Yes Album in 1971. Unlike Bill Bruford, who left to join King Crimson – a move that was far from certain to be successful given that group’s years of instability and consequent drop in sales – Wakeman’s leap into a solo career came with a generous safety net afforded to him by Six Wives…’ immense popularity at the time.