Water effects

Create real-time water effects

CLASSIC DEMOS

Ferenc Deák scared the LXF team with overly abusive mathematical formulae last month. Thankfully, that’s all water under the bridge now.

Part Four!

Don’t miss next issue, subscribe on page 16!

OUR EXPERT

Ferenc Deák is still stuck in the past for this instalment, but at least now he has cleaned his fridge.

Previously we have been experimenting with textures and mathematics, and have presented some effects that were heavily used in the compos of the old days. These effects are based on the distortion and clever manipulation of textures by algorithmically choosing texel points and presenting them on the screen using a formula.

Given the expansive scope of texture manipulation and its numerous applications, we are now introducing a complex effect based on this mechanism, which will yield surprisingly interesting results.

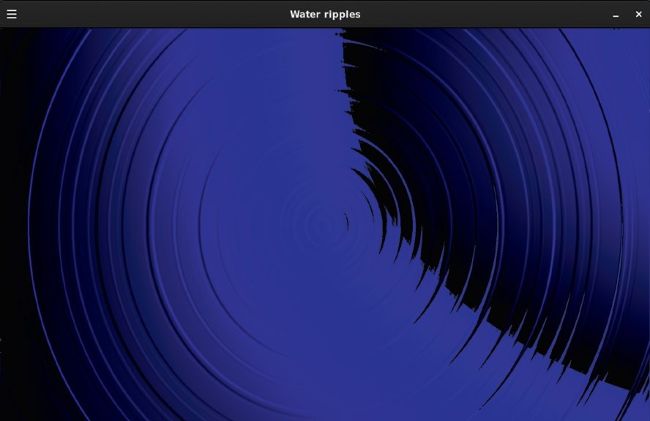

The effect we are presenting is the infamous water effect. Water can have several manifestations, such as raindrops, waves, a splash in the ocean – and all of these need similar but slightly different approaches. We are presenting the simplest of all: ripples caused by raindrops on a water surface. To keep things simple, we will have just one raindrop. Or maybe it’s a dripping tap. When implemented properly, we’ll see something like the blue screenshot (above-right).

Water you thinking?

Implementing water ripples is a bit more complex than anything we have done before, due to the very dynamic nature of the effect. As you can see in the screenshot, the ripples are nothing more than concentric circles, which grow in radius from the drop point, until they reach their maximum size, and then, after a while, calm down to their zen stage of nothingness.

The real-time calculation of drop circles for the effect would not be feasible, due to the complexity of the formulae, but we can come up with a very good approximation. We also want to keep things simple, as real-time simulation of fluids is a highly complex and energy-consuming task, so we’re just presenting the most basic and necessary elements to make this work.

In order to have a good approximation, we need at least two steps to the process; practically, this implies that the current state is dependent on the previous state. So, in order to draw the ripples for the current frame, we need to know how the ripples were drawn in the previous state. This can be dealt with as follows: int heightMap[2][SCREENSIZE_X * SCREENSIZE_Y] = {0}

what do you mean, it looks like a vinyl record?

Let’s not forget that we are manipulating a texture to behave like water that is being rippled, so this explains the name of the variable; it keeps the height of the various ripples at their current and previous stage for each pixel on the screen. In order to keep the sensation of movement, we continuously recalculate this map. Each step updates either the first or the second element of the array based on the ‘other’ stage of the map. This dynamic exchange of array indexes is done by a very simply trick in the updateScreen method that should already be familiar (if not, grab a previous issue of the magazine and check it out). void updateScreen(Uint8* screen, const std::vector& imageData) { static int dropletRadius = 5, currentHeightMapIndex = 0, dropletCounter = 0; dropletCounter++; calculateWater(currentHeightMapIndex ^ 1, WATER_WOBBLITY); for (int cc = 0; cc < dropletCounter; cc++) { waterDroplet(SCREENSIZE_X/2,SCREENSIZE_Y/2,cc *dropletRadius,dropletRadius*10, currentHeightMapIndex); smoothenWater(currentHeightMapIndex); dropletRadius+=4; } if (dropletCounter == 15) { dropletRadius = 0; dropletCounter = 0;}