MUSEUM PIECE

MOMI DEAREST

True cinema buffs have long been fascinated by the magic of movie museums and movie props. Mike Hankin looks at the history of such things, including the late, lamented Museum of the Moving Image in London...

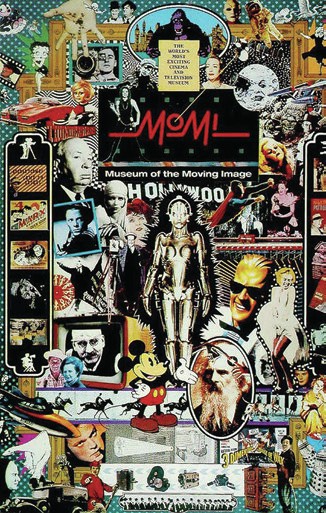

A poster for the Museum of the Moving Image (MOMI), a museum of the history of cinema technology and media sited below Waterloo Bridge in London. It was opened on 15 September 1988 by Prince Charles. The museum formed part of the cultural complex on the South Bank of the River Thames. MOMI was mainly funded by private subscription and operated by the British Film Institute. MOMI was closed in 1999, initially on a supposedly temporary basis, and with the intention of its being relocated to Jubilee Gardens nearby. Its permanent closure was announced in 2002

The cinema has always provided a vast array of material for the enthusiast to add to their collection, from posters, lobby cards and pressbooks, to the multitude of film-related magazines produced since the movies began. Many items can be bought for a reasonable amount, unless the collector is looking to add the rarer vintage material to his collection, then that is a different matter. At least as far as movie-advertising goes they were produced in sufficient quantity to give the collector a chance of finding something they are after, but the odds change when seeking something directly associated with the original film production. Then you are entering the realm of obtaining a potentially unique object.

Judging by the enormous amount of money that even the most mundane items fetch at specialist auctions, movie props have now attained an unexpected, long-lasting life, continuing years after the end of the productions for which they were initially created. Built to enhance an illusion, these objects were often discarded once their function had been fulfilled, with professional filmmakers for many years viewing them only as an ephemeral resource.

However, this eclectic mixture of movie paraphernalia would occasionally find their useful life lengthened by being retrieved from storage and sometimes modified to suit another film. Other times they were just left to rot on dust-covered racks, eventually suffering an ignominious end in a studio skip. A few choice ones would survive, as keepsakes of cast and crew or find their way into the private collections of the fortunate few. Then again, without these private collectors, many of these movie artefacts would have been lost forever.

It is quite feasible that the vast auctions held by major American studios MGM and 20th Century Fox to cash in on their dormant assets in the prop stores of their back-lots during 1970 and 1971, first brought the value of these items to the notice of the general public. The pleasure of owning a costume worn by Greta Garbo, Clark Gable or Judy Garland is somehow understandable and manageable, but what did purchasers intend to do with a chariot from Ben Hur (1959) or more amazingly the $15,000 paid for the full-size paddle-steamer from Showboat (1951)?

What mostly disappeared forever were the back-lots, perhaps only façades, but highly convincing streets, railway stations and more, extensively used before location filming became the normal route. Some sets would last only for a single film, such as the magnificent Roman Forum created in Spain for The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), bulldozed to make way for the Circus World (1964) tent, or even abandoned, such as the expensive Cleopatra set build at Pinewood in 1960. Isn’t it amazing, that sections of this multi-million-pound set would eventually end up being used to enhance the low-budget Carry On Cleo (1964), while the rest of the enormous structures ended up as a pile of rubble!