PL/ICredit: www.iron-spring.com

PL/I – the multifaceted language

Mike Bedford discovers the mysteries of PL/I, the language that IBM hoped would replace both FORTRAN and COBOL.

Part five!

Don’t miss next issue, subscribe on page 16!

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford is never one to turn down a new challenge. He discovered that trying PL/I is an interesting experience, but there are undoubtedly better languages today for real-world applications.

Despite our describing some of PL/I’s features as COBOL-like, there’s one very noticeable difference between the two languages. A bizarre concept in the design of COBOL, which PL/I did not mimic, was that statements should look like English language sentences.

The names of programming languages vary from the banal to the accurately descriptive, T via the totally meaningless or, in the case of this month’s subject, the downright inaccurate. The language in question is PL/I. The letter I is the Roman numeral for the figure one, which explains why it’s occasionally, incorrectly, shown as PL/1. It stands for Programming Language One, but it certainly wasn’t. In fact, two of the languages we’ve previously covered in this series predate it, as do several others.

To make it into our list of classic languages, a language has to have been around for a while, to put it politely, and PL/I certainly ticks that box, having been launched in 1964. It was designed by IBM for use on its System/360 mainframes, and was first used at its Hursley Laboratories in the UK as part of the 360 development programme.

To set the scene, let’s consider the main languages that had previously been promoted by IBM in the early ’60s. FORTRAN was used for scientific applications, and COBOL was used for business applications. While so much more basic, FORTRAN offered the same types of instructions provided by today’s common languages, but COBOL was very different. Because of its emphasis on data handling for commercial jobs, it became the first language to allow hierarchical data structures to be defined and subsequently manipulated. The aim of PL/I was to merge the features of these two languages and thereby provide a solution that would address the needs of both scientific or technical users and business users.

A PL/I syntax highlighting add-on is available for the Vi text editor – especially useful with an unfamiliar language.

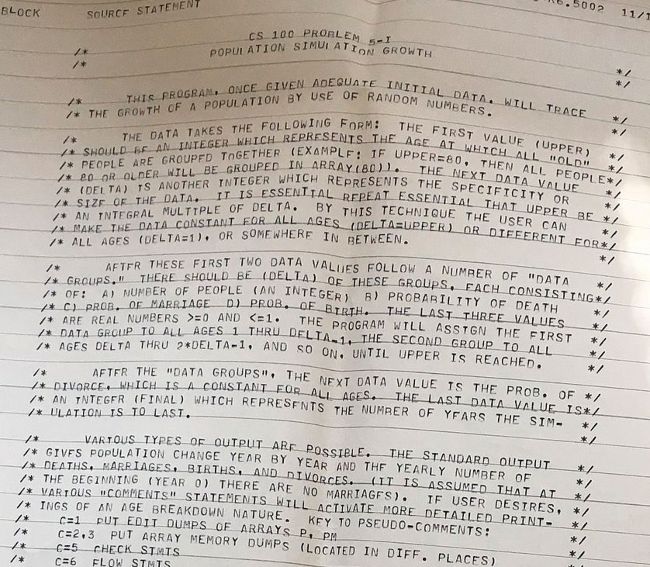

Multiple iterations, even of simple programs, are to be expected with a new language. But at least you won’t be using up whole forests in fanfold listings, as early PL/I programmers would have done.

But it went further. While virtually all the earlier languages had little in the way of features to support block-structured programming, ALGOL, our featured language in LXF302, and which appeared in 1960, did adhere to this important programming paradigm, so paved the way to nearly all today’s popular languages. ALGOL was never really promoted by IBM to any great extent but, even so, its block-structured approach also influenced the design of PL/I. We could almost think of PL/I, therefore, as a direct descendent of FORTRAN, COBOL and ALGOL, even though it didn’t have a great deal of success in replacing any of these languages.