TURING MACHINES

Programming a Turing Machine

It was the computer that started it all, albeit in theory. Mike Bedford shows you how to program a Turing Machine and put it through its paces.

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford is fascinated by how simple computer architectures – such as a Turning Machine – can do anything the most powerful supercomputers can do.

QUICK TIP

Alan Turning might not have built a physical realisation of his theoretical computer, but Mike Davey has. See www. aturingmachine. com. It works on a real tape, erasing old symbols and writing new ones as it goes. Behind the scenes it’s controlled by a Parallax Propeller microcontroller.

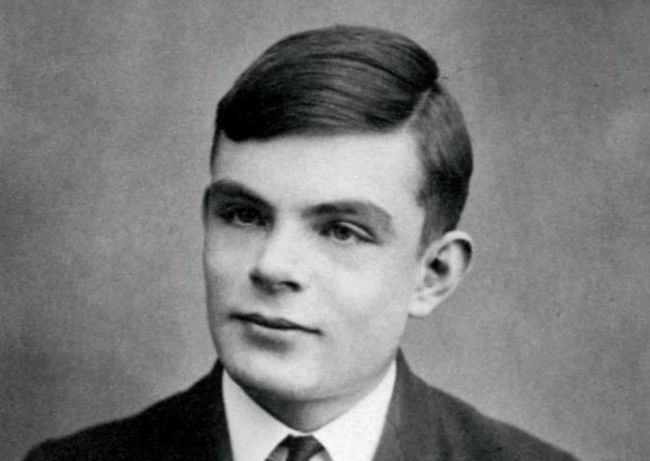

A lan Turing is probably best known for his pioneering work on code breaking at the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. In playing a key role in developing the electro-mechanical Bombe that was used to crack the Enigma cipher, Turing had a major impact on shortening World War II by an estimated two years and saving as many as 14 million lives.

Despite having been dubbed the “Father of Modern Computing”, however, his contributions to generalpurpose computing are less well-appreciated. And here it’s interesting to note that his design for the ACE computer, a cut-down version of which was eventually built by the National Physics Laboratory in 1950, predated the Manchester Baby, the world’s first stored program computer, by three years. Arguably, though, his biggest contribution to computing was his vision for a machine that was never actually built, and would have been totally impractical had it ever become a physical reality. This was the so-called Turning Machine and here we look at this model of computing and see how to program it using a couple of simulators.

Turning Machines

Alan Turing’s concept of the computing architecture that now carries his name dates back to 1936, which was almost a decade before anyone figured out how to build a universal computing device. But since this was a so-called thought experiment, a theoretical concept that he used to develop his theory of computability, it didn’t matter that it only ever existed on paper. What makes it so interesting to today’s programmers, though, is how simple it is compared to modern day computers, despite being capable of computing any function that the PC on your desk could compute.

If you’ve ever delved into historic computers you’ll no doubt have encountered some extremely minimalistic instruction sets. The Manchester Baby, for example, despite being a universal computing device, had just seven instructions, compared to many hundreds or thousands in today’s processors, as we saw in LFX264. Turning Machines are even simpler, not in having even fewer instructions, but in using an architecture that doesn’t really have instructions in the normal meaning of the word. So, possibly for the first time ever, you’d be writing programs that aren’t sequences of instructions. Instead, a Turning Machine is a special type of Finite State Machine, as we’re about to see.

Alan Turing’s famous Turing Machine was never intended as a physical computer, although today’s simulations have brought it to life.

(Credit: www.turingarchive.org/viewer/?id=521&title=4)