FILMING NEMO PART ONE

Prepare for vintage underwater thrills as Gregory Kulon looks back at the many screen versions of Jules Verne’s fantasy classics 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island, plus a bunch of waterlogged competitors!

A scene from The Mysterious Island (1929). Possibly the first talking, and first colour, featurelength science fiction movie, it is partially silent and partially monochrome

Many film historians consider 1939 to be the highpoint of Hollywood Filmmaking. In March of that year, MGM released its upcoming schedule of films for the 1939-1 940 season. As captured in the Los Angeles Times edition of March 21, 1939, MGM’s plans were to focus on only largescale productions releasing nearly one a week for the season starting in September. The announced films include some of the biggest Hollywood films of all time including The Wizard of Oz (1939), Gone with the Wind (1939), and Ninotchka (1939). Interestingly enough, the main film discussed in the announcement was one that never got made, an adaptation of the 1935 classic Sinclair Lewis novel “It Can’t Happen Here” about a fascist take-over of the United States Government.

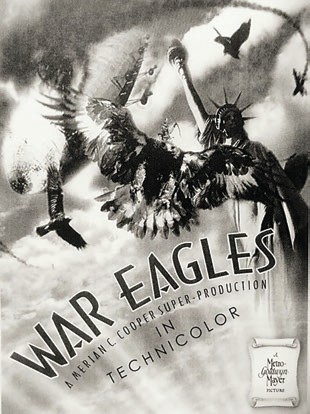

The list would also include two other large-scale projects that would not make the final cut, War Eagles and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Although many fans of fantastic films are familiar with Merian C. Cooper’s War Eagles project, almost nothing has ever been published on the latter Jules Verne adaptation.

By the late 1930’s, Merian C. Cooper was looking into getting another big project going. The man who had made a tremendous splash with his silent pseudo-documentary films Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925) and Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness (1927) had hit a peak in the history of fantastic films when he created and co-directed King Kong (1933). Even though that film propelled his career into the executive offices of RKO at the time, health issues and a desire for more control of his projects led him to branch off into more Independent production with his role as Vice President of Production at Pioneer Pictures.

While at Pioneer, Cooper worked to advance the use of colour photography. He would also make several projects with some of his favourite collaborators who had worked with him on Kong, including the genius who developed the incredible stop-motion animation effects for the film, Willis O’Brien. However, with the Great depression still limiting the budgets available, Cooper’s vision of what could be, especially with colour, became limited.

Both his film versions of She (1935) and The Last Days of Pompeii (1936) had to drop the use of colour, along with extensive scenes of spectacle, to fit within the budgets available.

Cooper would still influence the film business at Pioneer, especially with his work with John Ford to redefine the Western drama with Stagecoach (1939), but his grand visions were still too limited. He hoped that would change in June of 1937 when he began a new stint in his movie career by joining what was widely considered the preeminent studio at the time, Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Here was a studio that could think big and provide the necessary resources for his vision.

Merian C. Cooper in an undated publicity photo; A modern War Eagles poster mockup used for the cover of the Dave Conover Making of War Eagles book. War Eagles concept art by Duncan Gleason; Concept art for test Number 2 by an unidentified

MORE SPECTACULAR THAN KING KONG

Cooper’s main interest while at MGM was another brainchild of his that he felt could be more spectacular than King Kong. MGM published a multi-page full colour insert in the May 4th, 1939 issue of Film Daily to publicise their upcoming film projects.

In it, Cooper’s new project War Eagles would be described as “a novelty thriller combining imagination and living actors in a story of patriotic appeal; general treatment like that of The Lost World and King Kong; unprecedented production cost to bring you a sensational attraction.” This was the kind of support and showmanship Cooper was looking for.

Starting with a story treatment written by Cooper himself, War Eagles was to be an epic involving an aviator who finds a lost civilisation of Vikings living in the Antarctic. These Vikings ride massive eagles and even battle ape men and dinosaurs to survive in their environment. If that wouldn’t be spectacular enough, the film would end with the hero aviator, now riding his own White Eagle, leading an army of eagle mounted Viking warriors against a Nazi-like menace that is attacking the city of New York. The enemy has a new neutralizing ray mounted on a dirigible that will prevent all electrical items, including our fighter planes, from working. This would give the enemy fleet of fighter planes full control of the skies. The aforementioned “patriotic appeal” would be fully evident with crowds of citizens applauding the unexpected saving of New York as the young hero and his eagle watch from their perch on the shoulder of the Statue of Liberty.