Britain’s Finest Hour

One day above all others is remembered as ‘Battle of Britain Day’: 15 September 1940, a day that began just as any other...

September the 15th didn’t start well for Keith Park. Such were the strains of command that the New Zealand-born commander of the RAF’s No 11 Fighter Group had completely forgotten it was his wife’s birthday. Fortunately, Mrs Park was of a forgiving disposition and, having promised to give her a bag of German aircraft as a birthday present, he departed for work.

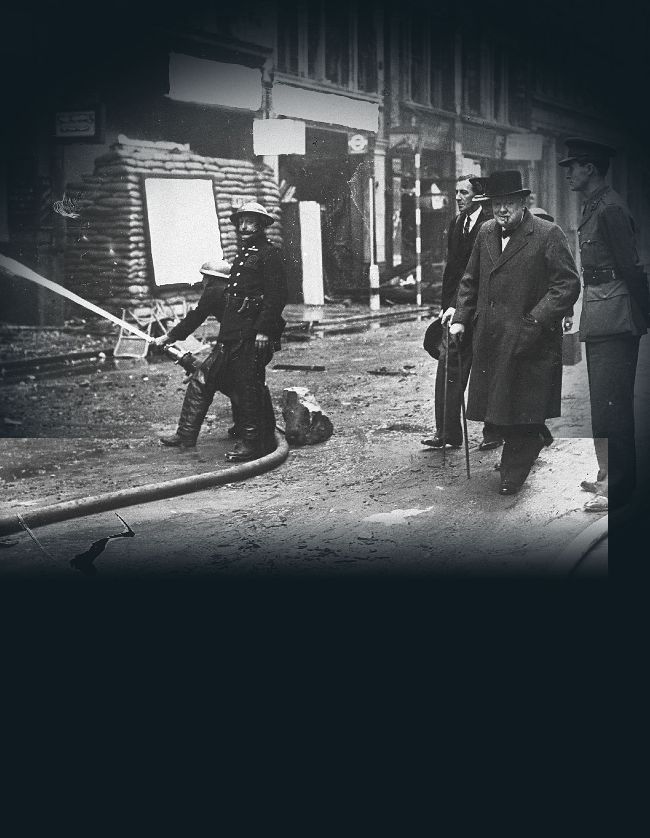

NO SIGN OFSURRENDER Censors removed anything that could give away Churchill’s location from this newspaper photo

PRESS ASSOCIATION

‘Work’ for Air Vice-Marshal Park was an underground control room at RAF Uxbridge, and it was from here that he supervised and co-ordinated the fighter defence of London and the South East against German air attacks. Mid-morning he received alarming news – the Prime Minister had decided to drop in to see how things were going. Churchill duly arrived and Park was faced with his first tricky decision of the day - how did one go about politely telling Britain’s leader that the control room airconditioning couldn’t cope with cigar smoke?

Meanwhile, at airfields across southern England, fighter pilots were awaiting the call to action. Most pilots awoke at dawn (to a cup of tea if they were officers) and waited for the lorry that would drive them out to the dispersal areas near their planes. While this was happening, ground crews would be hard at work on the planes, checking repairs, testing their engines and loading their machine guns. If everything worked and the plane was deemed ready for action, its petrol tank would then be filled with 85 gallons of high-octane fuel. The arriving pilots would take turns to grab some breakfast, either in huts near the planes or sitting in deckchairs outside a tent. Either way, the key thing was to be within sprinting distance of their aircraft.

544 The number of Fighter Command pilots killed in the Battle. The Luftwaffe lost 2,500 air crew

Across the Channel things were stirring. At about 10:10, a force of around 30 German Dornier bombers took off from their bases near Beauvais, north of Paris, and flew up to Cap Gris Nez, where they were due to rendezvous with several units of fighters before making for London. The fighters took off as planned at 11:00 but valuable time (and fuel) was wasted as the groups of planes searched for each other in the clouds before crossing the Channel. All the while, this activity was being picked up by British radar. Back at Uxbridge, and watched by Churchill, a WAAF put the first of what would be many markers on the control room map, while Park gave the order for the first two of his squadrons to scramble.