A History of the Scots Language

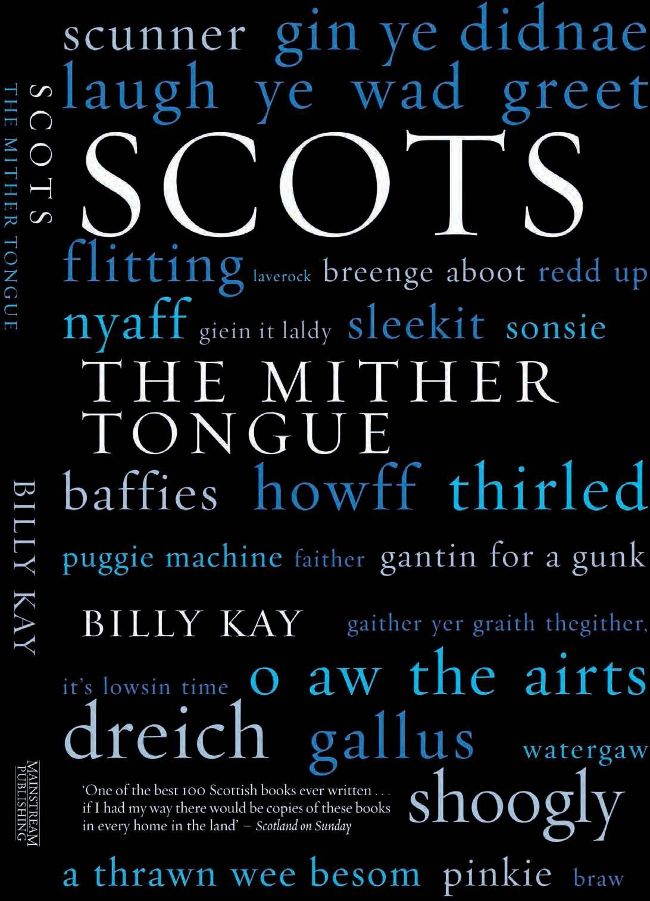

Billy Kay is the author of Scots The Mither Tongue and over the next few months, he will tell the story of the Scots language from its ancient origins to the present day.

by Billy Kay

To them, Scots was fine as a medium for couthy novels, newspaper cartoons, and music hall comedians

Part 7: Renaissance and Erosion

The status of Scots at the beginning of the 20th century derived very much from trends established in the 18th century and hardened in the 19th century. The language came to be regarded as a working-class patois, despised by the increasingly anglicised upper and middle classes. To them, Scots was fine as a medium for couthy novels, newspaper cartoons, and music hall comedians. When radio, cinema newsreel, and television eventually came along the Scotch stereotypes established in the music halls by Harry Lauder and his like were adopted by media dominated by Englishmen who cared little about reflecting the real Scotland, and less about the cultural sensitivities of her people. Besides, the Scots swallowed the myths and stereotypes themselves.

The upper classes and sections of the upper middle class spoke now in a manner scarcely distinguishable from the English of the Home Counties. Scottish R.P (Received Pronunciation). speakers may still pronounce the wh in whales to differentiate it from wales, and they may miss out the intrusive r in the Home Counties’ ‘Lawr and Order’, but to the majority of Scots they are speaking with an English accent. Edinburgh, with certain of its fee-paying schools specialising in teaching R.P., produces more such speakers than any other town. In all the other towns and cities, Standard Scottish English rather than R.P. tends to be the favoured medium. Coming from the West of Scotland, where an English accent meant that the person was English it came as a surprise to me at Edinburgh University that some Scots, and some patriotic Scots at that, could sound like Englishmen. The majority of Scots who are culturally anglicised, however, accept and rejoice in their anglicisation, for British society has conferred status on English culture, not Scottish. English is therefore perceived as the language for personal, social and commercial advancement. The resultant state of mind among many Scots is well put by William McIlvanney in his novel Strange Loyalties: “Scottishness may have been a life but Britishness can be a career”. Those who do speak Scots, and even many who speak Scottish English, nevertheless resent the prestige of R.P. and often regard their countrymen who speak it as cultural quislings. Strong feelings are raised on both sides of the linguistic divide in Scotland, and both the upper class and bourgeois contempt for Scots and the working class dislike of “posh English” are both reprehensible yet symptomatic of a country cut off from knowledge of its own cultural and linguistic history. Expressions of both sides’ attitudes are easy to find, the former in official educations reports, the latter in literature. 19th Century hostility to the vernacular on the part of the education authorities had continued, and in 1946 a Report on Primary Education described Scots in the following terms: the homely, natural and pithy everyday speech of country and small-town folk in Aberdeenshire and adjacent counties, and to a lesser extent in other parts outside the great industrial areas. But it is not the language of ‘educated’ people anywhere, and could not be described as a suitable medium of education or culture. Elsewhere because of extraneous influences it has sadly degenerated, and become a worthless jumble of slipshod ungrammatical and vulgar forms, still further debased by the intrusion of the less desirable Americanisms of Hollywood…Against such unlovely forms of speech masquerading as Scots we recommend that the schools should wage a planned and unrelenting campaign.

The result of this war of attrition, however, has not been an improvement in English, just a confusing resentment among those whose culture was the butt of this educational joke. Gordon Williams portrays well the linguistic confusion which the Scottish Education Department has wrought in this scene from his novel From Scenes Like These, where a young Ayrshire boy contemplates the speech of his environment.

Leggete l'articolo completo e molti altri in questo numero di

iScot Magazine

Opzioni di acquisto di seguito

Se il problema è vostro,

Accesso

per leggere subito l'articolo completo.

Singolo numero digitale

May/June 2019

Questo numero e altri numeri arretrati non sono inclusi in un nuovo

abbonamento. Gli abbonamenti comprendono l'ultimo numero regolare e i nuovi numeri pubblicati durante l'abbonamento.

iScot Magazine

Abbonamento digitale annuale

€35,99

fatturati annualmente

Abbonamento digitale annuale

€47,99

fatturati annualmente

Abbonamento digitale mensile

€4,99

fatturati mensilmente