LINUX HARDWARE

The hardware that made Linux great

Part Two!Don’t miss part three in next month’s issue!

Mike Bedford provides an expose of the RISC processors of the ’80s and ’90s and how Linux migrated to them from its beginnings on the 80386.

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford

had his first hands-on RISC experience with the Pi’s ARM-based chip, despite having been around to see some of the early RISC chips.

QUICK TIP

Despite representing very different philosophies, it’s generally thought that several of the dividing lines between CISC and RISC have been broken down since the ’80s. There are still RISC chips, and there are still CISC chips, but while we don’t have space to elaborate, we’ve seen some of them described as CISCy RISC and RISCy CISC, respectively.

Linux can trace its roots to the Intel 80386 – the only processor supported by the very first version of Linux – but the early ’90s computing landscape was a lot more varied than that. What’s more, it wouldn’t take long for Linux to embrace many of the up-and-coming alternative processor architectures and the computers they powered.

We’re going to look at some of the non-x86 processor families of the ’80s and ’90s that were designed to address the high-performance workstation and server market. They adhered to the RISC philosophy and, despite the market being served by several manufacturers, there was a surprising degree of similarity between their products. However, the different RISC processors had very different journeys.

CISC versus RISC

Today’s top two processor architectures, x86 and ARM, are often considered CISC and RISC designs respectively. It’s perhaps surprising, therefore, that we hear much less about the CISC versus RISC debate than we would have done in the ’80s. So, to start, we really need to summarise the old debate here.

Until the early to mid-’80s, the development of microprocessors involved, among other things, adding ever-more powerful instructions. The rationale seems quite convincing, and can be summed up with the phrase “hardware is fast; software is slow”.

Early microprocessors had very small instruction sets. They excluded things that have now been taken for granted, such as integer multiplication and division. As universal computers, they were able to carry out these functions, of course, but only by executing routines in software. Take an Intel 8088 subroutine that multiplies two 8-bit values to give a 16-bit result – it contains 13 instructions. However, it contains loops, so many more instructions would actually have been executed, typically around 90. Modern processors would execute these functions as just single instructions. Computers (or processors) that adhered to the philosophy of having ever-more powerful instructions came to be known as Complex Instruction Set Computers (CISC) when the alternative appeared.

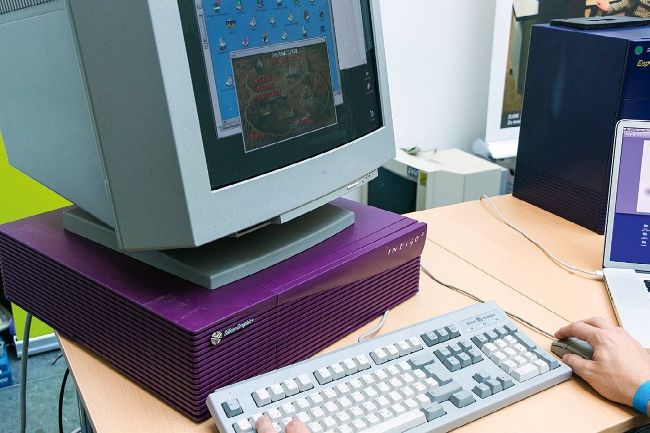

Many of the RISC-based workstations of the ’90s, like this SGI Indigo2, wiped the floor with contemporary x86-based PCs, and not just because of their fancy purple cases.