Consensus: Could Two Hundred Scientists Be Wrong?

STUART VYSE

Stuart Vyse is a psychologist and author of Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition, which won the William James Book Award of the American Psychological Association. He is a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

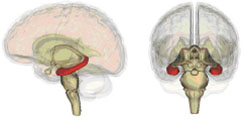

An illustration of the human brain showing the hippocampus (red area), one of the structures removed from Henry Molaison’s brain.

(source: Wikimedia)

In August of 2016, publication of a book about neuroscience’s most famous amnesia patient—known for decades only as H.M.—stirred up a controversy in the world of science. On August 3, the New York Times Magazine released an article adapted from Luke Dittrich’s book, Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets (Dittrich 2016a; 2016b). Two days later, on August 5, more than two hundred neuroscientists from around the world had signed a letter to the Times in support of Professor Suzanne Corkin, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientist who did most of the research with H.M (DiCarlo et al. 2016).

Henry Molaison (H.M.) suffered profound memory loss as a result of an experimental brain operation conducted in 1953 in an effort to control his epilepsy. The surgery removed most of Molaison’s hippocampus and some nearby structures on both sides of his brain, leaving him incapable of creating new episodic memories. Henry, who was the inspiration for the popular film Memento, could recall many things that happened to him prior to 1953, but after the surgery he couldn’t tell you what he had done five minutes before the present moment. As Dittrich put it in the New York Times Magazine article, “Each of the hundreds of times [he and Professor Corkin] met, it was, for Henry, a first meeting. . . .”

The Questions Raised

Sadly, Suzanne Corkin died in May of 2016, months before Dittrich’s book and the Times article appeared, and so it was left to her colleagues to defend her against what they believed was Dittrich’s “biased and misleading” description of Corkin’s work with H.M. On August 9, six days after the Times article was released and four days after the letter signed by the scientists appeared, Professor Corkin’s colleagues in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences got specific about their concerns, posting a letter on the MIT website outlining what Department Head James J. DiCarlo characterized as the “allegations” in Dittrich’s article (DiCarlo 2016a):

1. Allegation that (H.M.’s) research records were or would be destroyed or shredded. Given the importance of H.M. to the history of neuroscience, any destruction of primary data would be considered an enormous loss and possibly a violation of research ethics.

Leggete l'articolo completo e molti altri in questo numero di

Skeptical Inquirer

Opzioni di acquisto di seguito

Se il problema è vostro,

Accesso

per leggere subito l'articolo completo.

Singolo numero digitale

Jan Feb 2017

Questo numero e altri numeri arretrati non sono inclusi in un nuovo

abbonamento. Gli abbonamenti comprendono l'ultimo numero regolare e i nuovi numeri pubblicati durante l'abbonamento.

Skeptical Inquirer

Abbonamento digitale annuale

€19,99

fatturati annualmente