Fast Virtual Machines

Jonni Bidwell transcends meat space, ventures virtuously into the valleys of the virtual and returns laden with actual knowledge.

Virtualisation… where would we be without it? We don’t actually know, but life would certainly be harder. Thanks to virtual machines (VMs), home users can effortlessly boot all manner of other operating systems. Those might be exotic flavours of Linux or (since you surely don’t really need an actual install of this monstrosity anymore) a Windows VM for those odd times where it’s handy.

This can be taken to extremes, too.

Thanks to PCIe passthrough, which we covered back in LXF273, you can sacrifice a whole GPU to your VM, enabling it to run games (or CUDA simulations) arbitrarily close to native speed.

This time around we’ll look at a different but equally impressive technology in the form of Intel GVT-g. This makes it possible for us to segment newer Intel GPUs into virtual ones that can be seamlessly connected to our VMs. Unlike the passthrough method, this still enables us to use the GPU on the host.

Businesses, too, have a lot of love for the virtuals. VMs are highly portable and much easier to reinstantiate than regular machines in the event that the host running them catches fire. There’s also an efficiency improvement, in that a single machine can take on the role of several servers, and still enjoy the benefits of having those workloads properly segregated. Containers, of course, achieve this with even more efficiency, but at the cost of losing some of that segregation.

There are all kinds of tools for managing virtual machines at scale, so we’ll have a brief look at one of those, too. Specifically, we’ll show you that Vagrant makes it trivially easy to install Arch Linux.

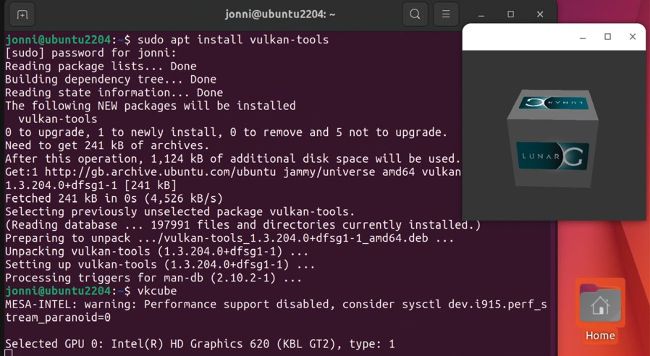

We’ll see later how you can get 3D acceleration working in your VMs, like the Vulkan cube demo.

Go beyond VirtualBox

Get your first VM running in seconds, with the simple elegance of Gnome Boxes…

Back in the mid-naughts, commodity CPUs learned a new trick. The idea had been around for a while, but the urge to make data centres ever more efficient really brought it to the fore. That idea was virtualisation, and on x86 platforms it first appeared in the form of Intel’s VT-x and AMD’s V on their early 64-bit CPUs. These instructions weren’t groundbreaking in themselves, but they did enable simple software (such as Microsoft’s Virtual PC or Sun’s – now Oracle’s – VirtualBox) to spin up virtual machines easily, thanks to being able to run a (largely unmodified) guest OS in a deprivileged environment.

It’s important to avoid confusion with emulation. Emulation is imitation, and to emulate properly everything must be imitated pretty much exactly. That means processor bugs, weird firmware logic and even the rotation of floppy disks all have to be simulated. And this is a slow process, even on a fast CPU. With virtualisation some hardware may be emulated, but the processor instructions from within the guest are run more or less verbatim on the host CPU. Anything can be emulated, but only machines of the same architecture can be virtualised. So this tutorial won’t help you create a virtual Apple M1 on your desktop box.

The Linux Kernel has its own hypervisor (a thing that runs virtual machines) called KVM. Others include VMware’s ESXi, Xen and the ubiquitous VirtualBox. VirtualBox is the de facto hypervisor for many a home user, because it’s easy to get started, it’s cross-platform and if you need something out of the ordinary there’s probably an easy option to get that working. But VirtualBox is made by Oracle, and while it’s open source (both the core and the guest additions are GPL2-licenced) that company doesn’t have a stellar reputation as stewards of FOSS.

Instead, we’d urge you to try Gnome Boxes. It’s a front-end for libvirt (a platform for managing VMs), which behind the scenes uses KVM and QEMU (an emulator that can also virtualise). Libvirt can happily talk to other hypervisors too, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Gnome Boxes is available as a Snap or Flatpak; however, our experience with the Snap wasn’t positive. So we’d recommend installing from your distro’s repositories. On Ubuntu you can find a Deb from the Software application. Click the drop-down labelled Source in the top-right to find it. Libvirt allows for all kinds of customisations, but Boxes is a delightfully simple application. So simple we’ve condensed set up of our first virtual box to a simple three-step dance (below).