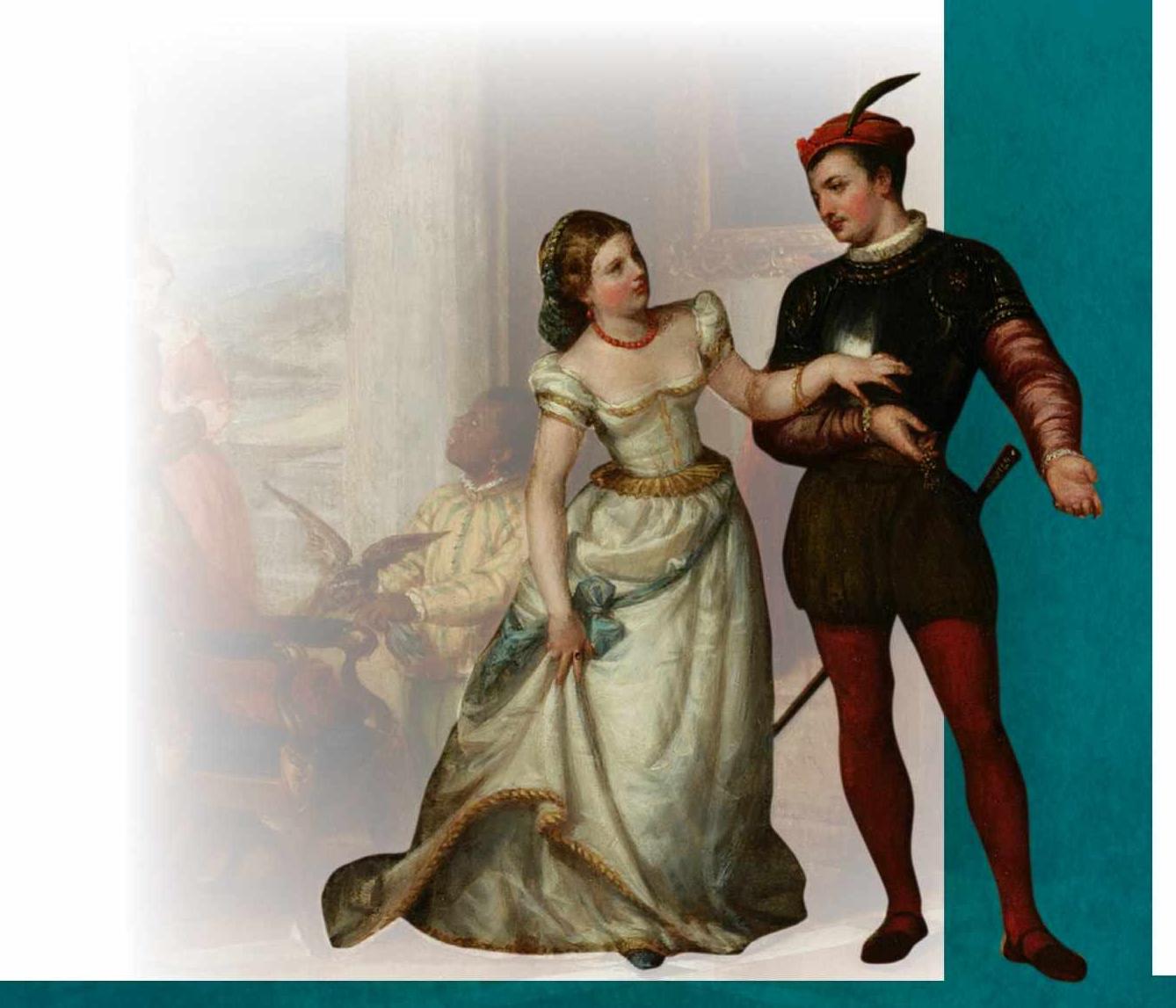

As Emma Smith notes, Bassanio (right) describes Portia (left) as wealthy “before he even mentions her name”

The Elizabethan theatre was a crucible for exploring changing ideas, including those about the economy. Shakespeare focuses on such ideas in The Merchant of Venice, with its concern about what was then a hot topic – what we’d now call capitalism. This was a moment of speculative enterprises and big profit, when the Merchant Adventurers, the Muscovy Company and the Virginia Company were exploring and exploiting the world’s resources and bringing them back to London. That’s what the merchant Antonio does in the play. As a result, he experiences a terrible moment when his fortunes are lost completely – reflecting the dangers of sea travel and the risks involved in that kind of investment.

Another fascinating, somewhat troubling and ambiguous figure is the Jewish moneylender Shylock. He helps people finance their operations or speculations, but is also despised by Antonio and his friends, who spurn him and call him a “dog”. Commercial lending was first made legal in England in 1545, when the limit for interest rates on loans was 10 per cent. Shylock’s outsider status as a Jewish person could be read as the play’s attempt to scapegoat these emerging financial models in a single character who can be externalised and punished, but I think what Shakespeare ultimately shows is that this doesn’t work. In fact, everybody in the play is implicated in this world of borrowing, lending and paying back at interest.