In 1980, Pink Floyd took to the stage at Earls Court, the cavernous 18,000-seater exhibition centre in west London. Booked for six nights in early August, the group performed a show that systematically parodied the very notion of an arena concert, introduced by an over-the-top MC, before sending four musicians onstage wearing Pink Floyd life masks; a surrogate band, proving that audiences at that distance could actually be watching anything. If that wasn’t enough to emphasise the dislocation, a physical wall was built between artist and audience made of 450 cardboard bricks.

Shining the spotlight on Roger Waters’ development as a live solo artist.

The Wall became Floyd conceptualist Roger Waters’ most complex idea, a reaction to the general isolation in his role as conflicted multi-millionaire socialist, but specifically at the dislocation he felt as his group played live to ever bigger, increasingly soulless arenas. Always a band received with earnest silence from their fans, yet since the global success of 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon, rowdy elements of the crowd, especially in North America, asphyxiated the already slender rapport Waters felt with his audience.

Fifty years almost to the month that Pink Floyd first played Earls Court, the Roger Waters This Is Not A Drill tour arrived at London’s O2 Arena, the 20,000-seat venue that effectively replaced the old exhibition centre, 13 miles to the west. A hall of this size is meat and drink to Waters, who now plays those venues with the ease of Sinatra in Vegas; he embodies the space with a showmanship that there wasn’t even a fleeting glimpse of in 1973.

But how did it come to this? How did a band, so experimental, stately and well-mannered get to this point? It all begins in exactly the same place, Earls Court, seven years earlier in May 1973.

While not exactly ladding it up the way Gary Kemp and Guy Pratt do with Floyd’s legacy in Nick Mason’s Saucerful Of Secrets, Waters is now showman provocateur, stalking the stage like an senior preening rock god, dressed in black with arms aloft to take his praise. His sense of humour is as black as his trademark T-shirt, as witnessed by the messages on his screens and his commentary before the shows, including the memorable missive: “If you’re one of those ‘I love Pink Floyd but I can’t stand Roger’s politics’ people, then you might do well to fuck off to the bar.”

There was much talk in early 1973 of Earls Court opening its doors to live concerts, yet there were few acts that could fill a hall of such size and scale. Built between 1935 and 1937, the storied venue was constructed on a triangle of land between train lines that had been used for

It wasn’t always like this for Waters live – when he presented his 1984 album The Pros And Cons Of Hitch Hiking at Earls Court for two nights, even the thrill of seeing Eric Clapton recreate David Gilmour’s parts couldn’t bring the crowds in. By 1987, his Radio KAOS tour dates often appeared in the US soon before or after David Gilmour’s Floyd’s comeback tour, meaning attendances were low. After his remarkable, star-studded performance of The Wall in a reunified Berlin in 1990, Waters didn’t appear live again until 1999 with his own In The Flesh tour. By the time he played Glastonbury in 2002, he’d been able to reinvent himself enough to be loved. By 2006 (albeit after Live 8) he was headlining Hyde Park Calling and playing Earls Court the following year for a final time on his The Dark Side Of The Moon tour. By 2011 Waters was performing The Wall live, which, at the time, became the highest-grossing tour for a solo artist.

Waters is able to do this with such élan with a band of thoroughly superb players and singers, including longtime Floyd collaborator Jon Carin, ex-REM drummer Joey Waronker, guitarist Dave Kilminster and, since the Us And Them tour, LA troubadour and solo artist Jonathan Wilson. Wilson’s appointment was a perfect match.

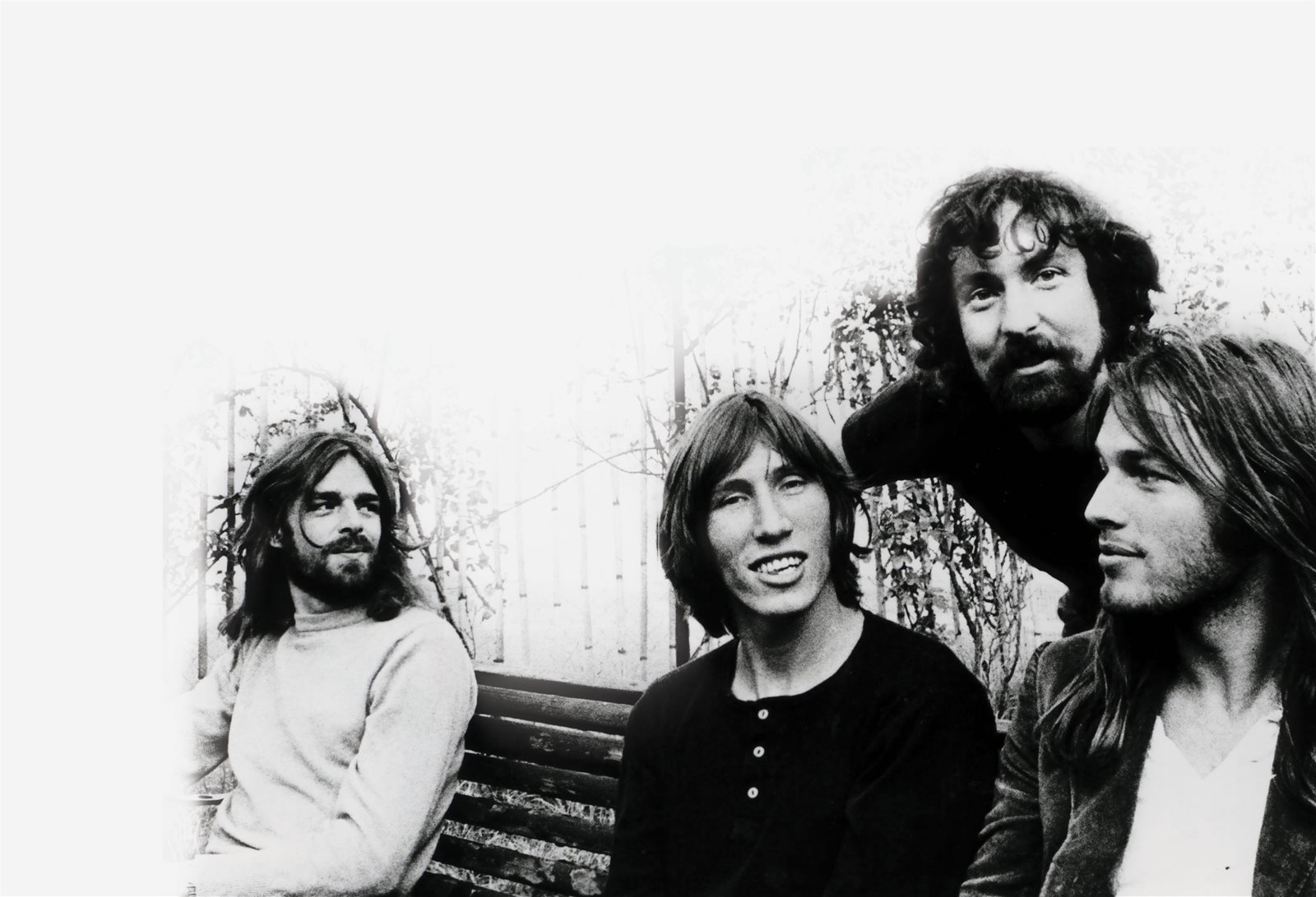

Happy bunnies: Pink Floyd in 1973.

Image: GEMA Images/IconicPix

“I happened to have The Final Cut and The Wall in my family record collection,” Wilson tells Prog from Laurel Canyon. “I loved The Final Cut particularly growing up, and also hearing Have ACigar on FM classic rock radio growing up was arresting; the bit where the low end all drops out!” Wilson is in a unique position, revered as a cult singer-songwriter, yet also able to enjoy the trappings of superstardom as he tours with Waters. “It’s really fun, and the entire band is stellar. We propel each other along, all the while supporting and backing the man.”

“Roger started getting really upset later, after Money became a success. We became more famous and the gigs got larger; intimacy was lost.”

Wilson is far from unnerved when fans sing every word back at him. “That lets you know they love the songs – their minds are being blown the whole show, from my view.”