MOVING THROUGH SOME Changes – How 90125 Saved Yes

The short-lived Drama era in 1980 was almost the death of Yes. Yet three years later, the heroes of British progressive rock had been complete ly reinvented with massi ve worldwide success. In 90125 they had their biggest-selling album and a worldwide hit single. On the record’s 40th anniversary, we look back on how a new band without a deal became an 80s success story.

Words: Stephen Lambe

They were Yes before and they were Yes after. But what on earth happened in between?

Ebet Roberts/Redferns/Getty images

In January 1981, Yes met at Steve Howe’s house in Hampstead. The previous year had been a fraught one for the band: following the departure of Jon Anderson and Rick Wakeman, the three remaining members – Chris Squire, Alan White and Howe – had recruited Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes from the new-wavers The Buggles. The resulting album, Drama, remains a fan favourite, but was created under extreme pressure with a US tour only months away. During the shows that followed, Horn frequently struggled to fill Anderson’s shoes. All was not well.

“I told Chris that it sounded a bit like Yes. To which Chris said, ‘That’s why you’re here.’”

Jon Anderson

Horn was effectively fired after the tour, and Squire and White announced a plan to form a new project with Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin. This left Howe and Downes holding the baby, with no appetite to continue as Yes. Within months, the remaining duo joined forces with John Wetton and Carl Palmer to form Asia, while Horn made the second Buggles album and started a production career. Then manager Brian Lane was horrified: he’d lost Yes and the band went on to lose their record contract with Atlantic.

The few months that White and Squire spent rehearsing with Page as part of XYZ are the stuff of legend. Page, himself reeling from the death of John Bonham just months before, was initially enthusiastic and the trio pooled material, producing several demos. It didn’t take long, however, before the relationship began to fall apart, scuppered by both musical and managerial disagreements. At a loose end once more, the pair teamed up with lyricist Peter Sinfield and recorded a Christmas single, Run With The Fox, which was released towards the end of 1981. It’s since become something of an unsung classic in the Yuletide sing-along genre.

A bootleg copy of the XYZ/ Cinema sessions.

Although XYZ never recorded an album, it’s clear that the two former Yes men had music in mind that was a little more contemporary in tone, even compared to the energetic prog of Drama. Some pieces from those rehearsals would wind up on later Yes albums: the Squire song Telephone Secrets, which never found a home with Yes, shows a band combining musical chops with commercial aspirations. This would become the template for their new band, Cinema.

Meanwhile, South African guitarist Trevor Rabin was also at something of a crossroads. Following fame in his homeland as part of Rabbitt, he had moved to the UK and released three solo albums on the Chrysalis label before a songwriting development deal with the new Geffen label led to him suddenly moving to California. However, things started to turn sour, and after a period rehearsing, ironically, with Howe and Downes’ Asia in London, he was unceremoniously dropped by Geffen. However, Rabin wasn’t short on interest.

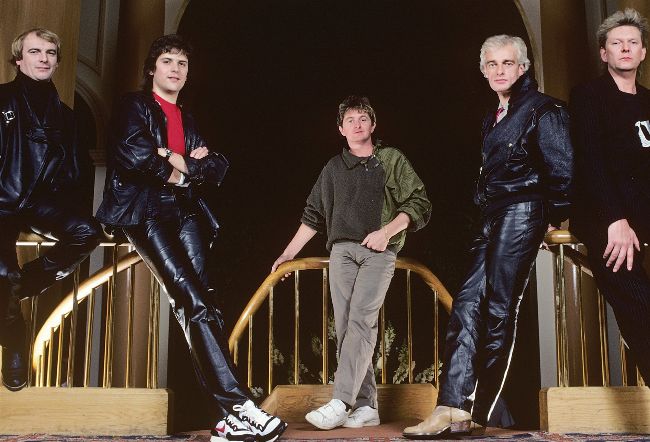

August 1980 line-up, L-R: Alan White, Geoff Downes, Chris Squire, Trevor Horn,

Steve Howe.

MICHAEL PUTLAND/GETTY IMAGES

“I started sending out demo tapes,” he remembers. “The irony is that I sent out all this material that was going to end up on 90125, like Owner Of A Lonely Heart and Changes, and they were rejected. I’ve still got the letter from Clive Davis at Arista saying, ‘While we feel your voice has Top 40 appeal, we feel your song [Owner…] is too left-field for the marketplace today.’”

Other offers came in.

“There was talk of a band with Keith Emerson, Cozy Powell and Jack Bruce, but that idea didn’t move forward,” Rabin remembers. “Then Ron Fair, a fantastic A&R guy at RCA, offered me a solo deal, so it was that: the band with Keith and Jack or the possibility of a band with Chris Squire and Alan White via Phil Carson at Atlantic, who had also heard the demos. In the end, Phil – who’s a pretty persuasive guy – called me up and said, ‘Come on, stop fucking around.’ So the next thing I knew, I was in a sushi restaurant in Shepherd’s Bush [west London] getting to know Chris and Alan.”

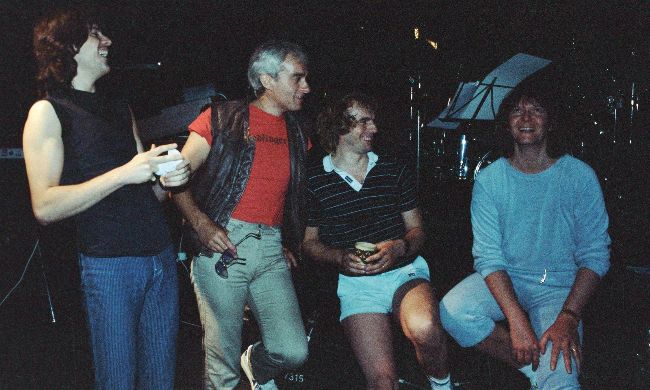

The band, then known as Cinema, share a laugh between rehearsals at John Henrys.

DAVID WATKINSON

At the end of the evening, the trio went back to Squire’s house in Virginia Water in Surrey and had what Squire referred to as “the worst jam in history”. Rabin agrees: “It didn’t sound great, but it felt so right.”

Squire, Rabin and White found themselves in another development deal financed by Phil Carson personally, with the freedom to work on material at their own pace at John Henrys rehearsal studio in Islington, north London. Carson already had a long history with Yes. As an executive at Atlantic, it was he who had convinced the label to re-sign Yes after their second album, Time And A Word, flopped in the US. He’d also introduced Yes to long-time engineer Eddie Offord and had stayed in close touch with the band, especially Chris Squire, throughout their success in the 1970s. But the group needed a keyboard player, and both Carson and Squire saw the logic of bringing in Tony Kaye, Yes’ original keys man. Carson confirms that even at this early stage, it was in his mind that Yes should be revived while the band rehearsed.

“The next thing I knew, I was in a sushi restaurant in Shepherd’s Bush getting to know Chris and Alan.”

Trevor Rabin

“Part of my job is being a marketing guy. A new band is difficult to sell. An established one is much easier,” he acknowledges. So, having Kaye in the band would take the line-up closer to being Yes from day one. As a bonus, Kaye had a certain charisma, and the way he played would also suit the new band. Squire, however, had the job of selling the idea to Rabin.