MYSTERIES OF THE UNIVERSE

WHY IS MARS STILL VERY MUCH ALIVE?

A mantle plume may be causing volcanic and seismic activity on the Red Planet

Reported by David Crookes

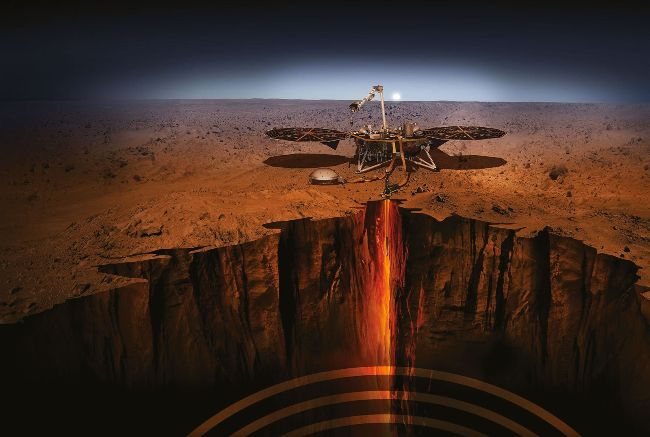

NASA’s Insight probe was thought to have landed in a geographically boring region of Mars. Instead it appears to have landed on an active plume head

F or a long time, scientists believed that Mars was not only red, but dead. This didn’t make the planet any less interesting, since there’s F evidence of rivers flowing into lakes and the potential that Mars may have once harboured life. But just one look at this small, ghostly world appears to suggest that it’s a largely dry and dusty husk. Not much, it has been assumed, has happened on Earth’s neighbour for the past 3 billion years. Or so it was thought. “The geological history of Mars was understood to be very simple,” says Adrien Broquet, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “The planet formed at the same time as Earth some 4.5 billion years ago, and there was a tremendous amount of volcanism about 3 to 4 billion years ago. Enormous volcanic activity formed the largest volcanoes in the Solar System, for example Olympus Mons. Since then, Mars was understood to have slowly cooled down, with less and less volcanic activity.”

After 2018, the scientific perception of Mars began to change. That year, NASA launched the InSight mission, which sent a lander to the Red Planet to investigate its interior structure and composition. By studying Mars’ crust, mantle and core, the mission sought to get to the bottom of how rocky planets formed in our inner Solar System while also determining the level of tectonic activity on Mars. “Before the mission, we kind of expected marsquakes – quakes on Mars – to come from everywhere on the planet, being due to the planet slowly cooling and contracting,” Broquet explains. “What we found instead was one particularly active region where maybe 90 per cent of the marsquakes were recorded – some 1,300 in the four years of the mission. This region is called Elysium Planitia, and we didn’t know why marsquakes would come from this area specifically. I was doing my PhD in the south of France when we slowly began to understand that this region was seismically active.”