THE MOJO INTERVIEW

JOE BOYD

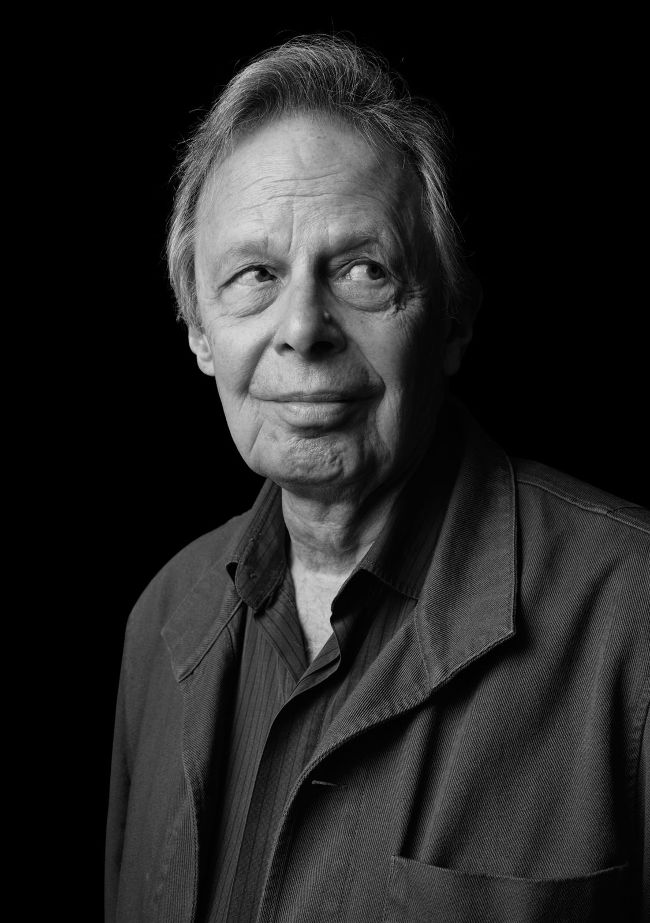

Scenester-savant, peerless producer of folk-rock and more, and now author of the War And Peace of world music, a philosopher of pop guides us through seven decades of sound. “I wanted to be the perfect listener,” says Joe Boyd.

Interview by JIM IRVIN • Portrait by TOM OLDHAM

Tom Oldham, David Kaptein

ON SUNDAY, MAY 10, 1964, AT THE Hammersmith Odeon, London, a visiting 22-year-old American, raised in Princeton, New Jersey, decided that Britain was his spiritual home.

The event was an all-star package show headlined by Chuck Berry. Joe Boyd was standing in front of the stage, where he’d been taking photographs, surrounded by teenage girls screaming for Chuck. From his vantage point, he spotted John Lee Hooker standing in the wings watching Berry play. Boyd exclaimed, “Oh look, there’s John Lee Hooker!”

The girls followed his gaze and all started screaming and calling, “We want John Lee! We want John Lee!” Berry, unsurprisingly, was annoyed by the interruption, but invited Hooker to come out and take a bow. Hooker did so. The girls screamed.

These, Boyd saw, were no blues purists, simply regular teenage pop fans, but they recognised and cared who John Lee Hooker was, something which applied to only his hippest Harvard friends back home, and he suddenly thought, “This is where I should be.”

He’d come here as the very green young tour manager for another package tour of blues performers featuring Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Muddy Waters. He would return in November 1965 as the newly appointed head of Elektra Records’ European office. He would discover, manage and produce The Incredible String Band. He would found, with countercultural linchpin John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, the UFO club, fomenting the underground scene in a basement off central London’s Tottenham Court Road. He would produce The Pink Floyd’s debut single, Arnold Layne, and steer his Witchseason Productions stable at Island Records where he discovered, managed or produced Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, Nick Drake, John and Beverley Martyn, Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood Of Breath, and many more. As a producer, be it for Vashti Bunyan, Defunkt or Toumani Diabaté, he’s favoured warm, dynamic, transparent recordings that capture people in a room together, and has aimed to be “the perfect listener”.

When Witchseason hit the financial buffers, Boyd accepted a new post in Hollywood in 1971, entering a rocky period navigating the movie business. He returned to Britain, and music, as the chief of Hannibal Records in the ’80s, where he championed ‘world music’, a tag he’d helped create to promote non-Anglo-American pop of all flavours.

As this century dawned, Boyd figured the music business no longer required him, so he wrote an excellent memoir about his adventures, White Bicycles (Serpent’s Tail, 2006). He next turned his attention to a wide-ranging book about ethnic music’s greatest hits. Published this month, And The Roots Of Rhythm Remain, is an 800-plus-page tour de force that took almost 15 years to complete.

Now in his eighties, still twinkly and still happily resident in London, Boyd has witnessed modern pop’s entire history, from the very dawn of rock’n’roll to the dominance of TikTok. How does he think it went?

“It was all going fine until the invention of the drum machine,” he laughs.

Congratulations on the book. It’s vast and detailed without ever being dry or scholarly. What made you start it?

The original germ of the idea was [Paul Simon’s] Graceland, because so much of the liberal middle class that was lapping up that record and Ladysmith Black Mambazo felt virtuous about their enthusiasm for South African music. It worked, it was a huge game-changer in the battle against apartheid, but I knew that wasn’t the story. The story was the Zulus. The thing that narked the ANC about Paul Simon was not so much that he was breaking the boycott but that he was working with the Zulus, who were fighting the ANC in deadly battles every day. And nobody in the northern hemisphere knew that.