REAL GONE

My Lord, What A Livin’

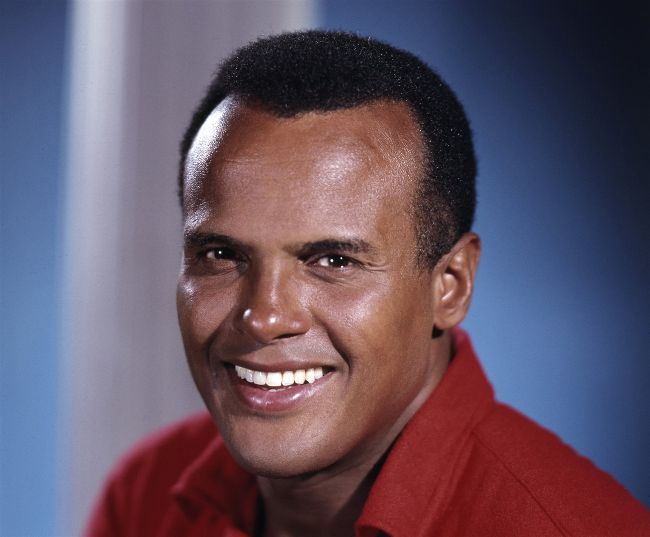

Harry Belafonte, who used the stage to help reshape his country, left us on April 25.

Harry Belafonte: the singer, actor and activist eroded racial lines and offered a crucial template for the modern musical polyglot.

Getty

IN FEBRUARY 1968, Harry Belafonte stepped in front of the camera and into the United States’ tumultuous breach.

Johnny Carson asked Belafonte to take a turn as guest host for his popular Tonight Show, but the singer, actor, and activist was not content with being merely late-night’s first black host. His interviewees, he demanded, needed to be integrated, too, a rarity in those days of the seemingly immortal Jim Crow. Belafonte succeeded, cajoling longtime confidant Martin Luther King Jr. into cracking a joke, marvelling at Buffy Sainte-Marie, and gabbing with the likes of Dionne Warwick and Sidney Poitier. These were the heady days just after the Tet Offensive, Richard Nixon’s presidential announcement, and what would prove King’s final sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church. Belafonte was a disarming and serious arbiter, a momentary eye in a country’s worldwide storm.

“Purism is the best cover-up for mediocrity.”

HARRY BELAFONTE

By that point, Belafonte had been a superstar for much more than a decade, his multinational folk synthesis earning him controversial coronation as the ‘King of Calypso’ and his suave acting earning him roles that eroded racial lines (he had gone to acting school with Marlon Brando, his late-night jazz buddy). His presence was so striking that movie houses, especially in the American South, cancelled screenings because they were “stirring up trouble”.

Belafonte was born in Harlem in 1927 to mixed-race parents who had immigrated from Jamaica. He spent several years in the West Indies, swimming and, as he told a Carnegie Hall crowd, “listening to the songs and the stories that the sailors used to tell.” Inspired in part by the raw truth Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie delivered during a Village Vanguard performance, he became a magpie of international folk, not only delivering the sounds of the Caribbean to a country craving exotica but also singing Jewish wedding songs, Irish ballads, and African-American work numbers. Belafonte offered a crucial template for the modern musical polyglot. “Purism,” as he said in 1959, “is the best cover-up for mediocrity.”

But as the Carson episode verifies, Belafonte never regarded himself as an entertainer. Instead, he wielded his stardom (and concomitant wealth) as a tool for his nation’s most vulnerable in the battle for continuing civil rights. He bailed King out of Birmingham’s infamous jail and, alongside Poitier, outran the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan to deliver $70,000 in cash to Freedom Summer organisers. In fact, his activism outlived his artistic ambitions. Recorded in Johannesburg, his final studio album, 1988’s Paradise In Gazankulu, railed against apartheid. After the election of Donald Trump, he advised the Women’s March in Washington DC and, three years later, lampooned “the empty promises of the flimflam man” in The New York Times. Belafonte remained dauntless, an enduring model for tandem citizenry and celebrity.

Belafonte died in late April at home in New York – at 96, he was just shy of an American century, during which he helped fulfil his country’s grandest ideals, however tenuous he knew they might prove.

Grayson Haver Currin

Mark Stewart

Pop Group orator, reality prison escapee

BORN 1960

AS MARK STEWART told MOJO in 2015, there could be a “supernatural” aspect to the work of The Pop Group, the Bristol post-punk firestarters he fronted from 1977. “I don’t know how it happens,” he said, “and I wouldn’t want to control it.”

For more than four decades of what he called “walking between worlds”, Stewart acted as lightning conductor, channel and communicator, transmitting confusion and stark clarity in equal measure to protean and visionary soundtracks. With The Pop Group, funk, dub, free jazz and Situationism were among the dissident mind-viruses vomited forth to a near-unbearable degree on the albums Y (1979) and For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder? (1980). Singles including She Is Beyond Good And Evil and We Are All Prostitutes similarly recast reality in their own image, but unclassifiable and ungovernable, the band split in 1981, having altered the DNA of Bristol music for decades to come. Massive Attack hailed Stewart as “original chief rocker”; another admirer further afield was a young Nick Cave, who called him an “unbelievably exciting frontman to whom I am deeply indebted.”