Android dreams

Artificial Intelligence has made remarkable advances but it may never replicate the human mind. By Philip Ball

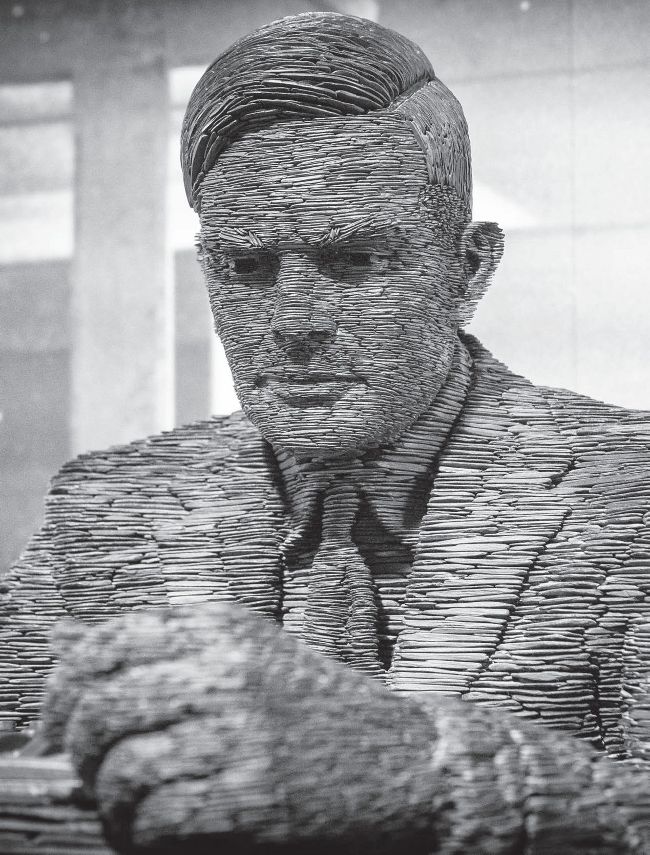

The test of time: a slate statue of Alan Turing outside Bletchley Park

© STEVE MEDDLE/SHUTTERSTOCK

Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust

by Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis (Ballantine, £24)

Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans

by Melanie Mitchell (Pelican, £20)

As well as playing a key role in cracking the Enigma code at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, and conceiving of the modern computer, the British mathematician Alan Turing owes his public reputation to the test he devised in 1950. Crudely speaking, it asks whether a human judge can distinguish between a human and an artificial intelligence based only on their responses to conversation or questions. This test, which he called the “imitation game”, was popularised 15 years later in Philip K Dick’s science-fiction novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? But Turing is also widely remembered as having committed suicide in 1954, quite probably driven to it by the hormone treatment he was instructed to take as an alternative to imprisonment for homosexuality (deemed to make him a security risk), and it is only comparatively recently that his genius has been afforded its full due. In 2009, Gordon Brown apologised on behalf of the British government for his treatment; in 2014, his posthumous star rose further again when Benedict Cumberbatch played him in The Imitation Game; and in 2021, he will be the face on the new £50 note.

He may be famous now but his test is still widely misunderstood. Turing’s imitation game was never meant as a practical means of distinguishing replicant from human. It posed a hypothetical scenario for considering whether a machine can “think.” If nothing we can observe in a machine’s responses lets us tell it apart from a human, what empirical grounds can we adduce for denying it that capacity? Despite the futuristic context, it merely returns us to the old philosophical saw that we can’t rule out the possibility of every other person being a zombie-like automaton devoid of consciousness but very good at simulating it. We’re back to Descartes’ solipsistic axiom cogito ergo sum: in essence, all I can be sure of is myself.