NEUTRINOS

GHOST PARTICLES OF THE MILKY WAY

Neutrinos… they’re everywhere, yet almost impossible to detect. But neutrinos generated in our Galaxy have now been picked up for the first time, with potentially major consequences for our knowledge of cosmic rays, supermassive black holes and the rest of astrophysics

by MARCUS CHOWN

CREDIT: RAFFAELA BUSSE/ICECUBE/NSF

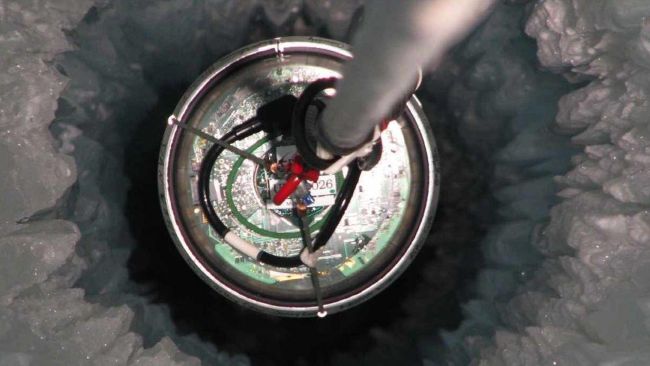

Neutrinos hitting the IceCube detector produce Cherenkov radiation, leaving trails of blue light

A Digital Optical Module (DOM) is lowered into the ice

How do you detect the undetectable? That’s the challenge scientists have faced since the most ghostly, elusive subatomic particle, the neutrino, was posited nearly a century ago.

Yet now they’ve been detected.

In June, neutrinos generated from elsewhere in the Milky Way were spotted. It’s the first time we’ve seen anything but photons of light from our Galaxy. The particles are tiny, but the discovery is huge.

“We’re truly at the dawn of neutrino astronomy,” says Steve Sclafani of the University of Maryland, one of the scientists involved in the project.

“NEUTRINOS ARE THE SECOND MOST ABUNDANT SUBATOMIC PARTICLES”

It’s fair to say neutrinos are strange. They’re the secondmost abundant subatomic particles in the Universe, after photons, but they’re extraordinarily elusive. So rarely are they stopped by anything in their path that, when Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli proposed their existence in 1930, he apologised to his fellow physicists.

“I have done a terrible thing,” he said. “I have predicted a particle that can never be detected.”

To get an idea of just how elusive they are, hold up your thumb. Every second, about 100 billion neutrinos from the core of the Sun stream through your thumbnail, and almost none of them are stopped by it.

Pauli bet a case of champagne that nobody would ever detect a neutrino. But towards the end of his life, he lost that wager.

On 14 June 1956, Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan announced that they’d picked up neutrinos streaming out of a nuclear reactor at the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina. Their trick was to create a target that contained a vast number of atoms, thus boosting the chance that at least one of the elusive neutrinos would be stopped.