Beyond reasonable doubt

Climate science and the limits of appropriate scepticism

LAWRENCE M KRAUSS

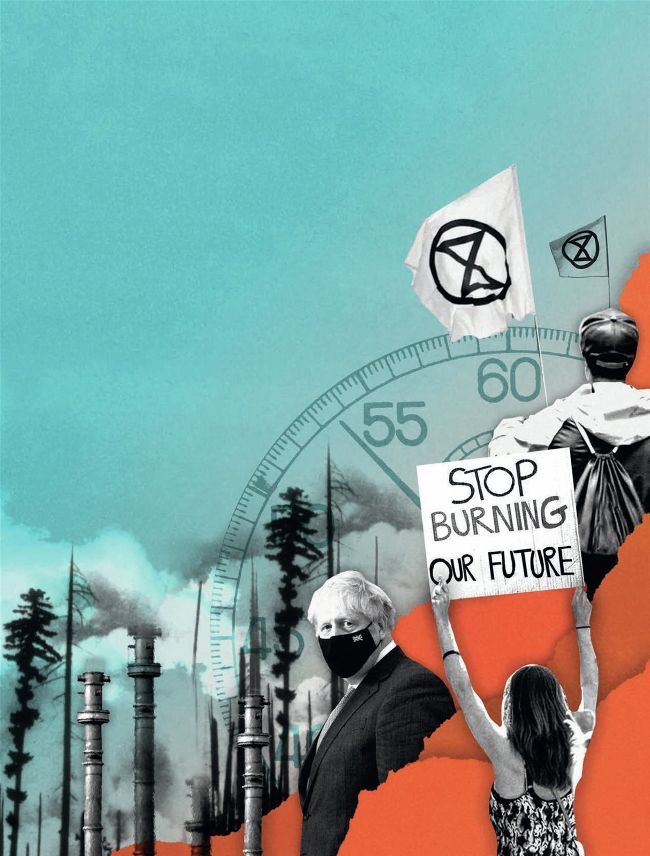

ILLUSTRATION BY HAYLEY WARNHAM

When the detective Dirty Harry points his huge gun at a criminal, he states that there is some doubt about whether the chamber that is currently cocked is actually loaded. The policeman then utters the movie’s famous lines: “You’ve got to ask yourself a question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do you punk?”

In a sense, this question captures the state of debate about climate change on the cusp of the COP26 global summit in Glasgow. Quantifying uncertainty is always a crucial part of science. In the Dirty Harry example, a thoughtful criminal will first infer a one in six chance of dying (assuming one loaded chamber in a six-chamber pistol) before deciding whether fleeing is worth the risk.

Similarly, to decide whether recalcitrant governments at the forthcoming summit are unwisely pushing humanity’s luck, it’s best to focus on the well-established science whose uncertainties can be quantified. It’s reasonable to suspect the wilder speculations of doom, and it’s obviously reasonable, too, to doubt whether a particular detailed and specific prediction will be accurate. But it’s not reasonable to deny that we’re running some risks the existence of which has been well established. Gauging what can and cannot reasonably be doubted is indispensable to settling just how “lucky” we can feel. But it can be tough to glean what is sure and what is dubious in a “debate” that is mired in emotion, politics, money and sensationalism as much as it is in science.

The lurch away from science is not hard to understand. Some socialists might welcome a wholesale reworking of the business model of modern industrial civilisation which they judge, rightly or wrongly, to be a happy requirement of dealing with the climate crisis. Hair-shirted puritans, meanwhile, may enthusiastically embrace the darkest scenarios almost because of the implied need for immediate dramatic restrictions on energy production, consumption and travel. For others, including libertarians in particular, this restriction of “personal freedom” is anathema: they will thus have an ideological reason to doubt apocalyptic predictions. In such ways, and even before we get to the potential of vested personal interests that distort one’s reading of science, a person’s immediate reaction to the issue of climate change tends to become deeply entangled with their political DNA.

The debate is now reaching a new level, with the release this summer of a dire new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), its first major assessment of global climate change in eight years, warning of potential disastrous consequences if carbon emissions are not curtailed in the coming decade. The UN secretary general António Guterres labelled the report “a code red for humanity,” as the new administration in the United States looks set to use the coming summit as an attempt to return to a position of leadership on the climate issue.

But just how much can Washington, or even the IPCC, be reasonably sure of? Developing sound public policy proposals in the current intellectual climate—never mind winning wide political approval for painful choices—will be challenging until we can agree on what it does, and does not, make sense to doubt.

Irreducible uncertainties

Leggete l'articolo completo e molti altri in questo numero di

Prospect Magazine

Opzioni di acquisto di seguito

Se il problema è vostro,

Accesso

per leggere subito l'articolo completo.

Singolo numero digitale

November 2021

Questo numero e altri numeri arretrati non sono inclusi in un nuovo

abbonamento. Gli abbonamenti comprendono l'ultimo numero regolare e i nuovi numeri pubblicati durante l'abbonamento.

Prospect Magazine