Sense of WONDER

Join MOJO as we leaf through the chapters of his life and work, his visions and melodies, and shake your head in Wonder…

Sixty years since Fingertips hit Number 1 and turned his young career around, STEVIE WONDER is still working on music that bathes the soul, battles injustice, and blows the minds of his peers. How he got here is astonishing in itself: the blind prodigy who escaped Motown’s scrapheap twice to make some of the most beautiful and ambitious pop music ever conceived.

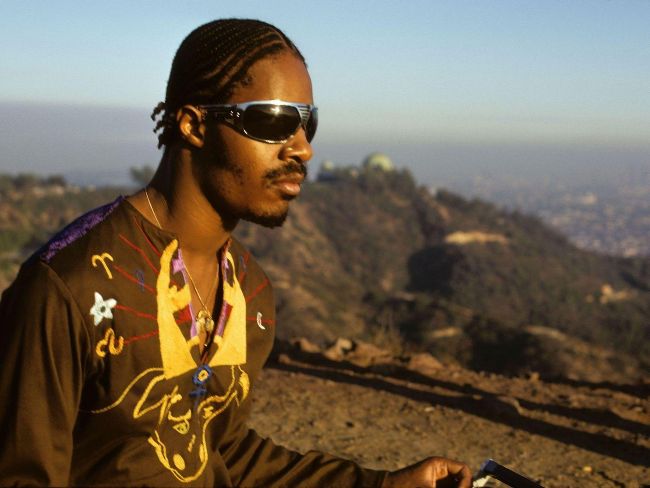

Golden years: Stevie Wonder at the peak of his powers, Griffith Park, Los Angeles, September 15, 1972.

Portrait by JEFFREY MAYER.

STEVIE WONDER 1950 -1970

The Young And The Restless

The rise, fall and rise again of ‘Little’ Stevland Judkins, a talent never contained by Motown’s straitjacket.

By DAVID HUTCHEON.

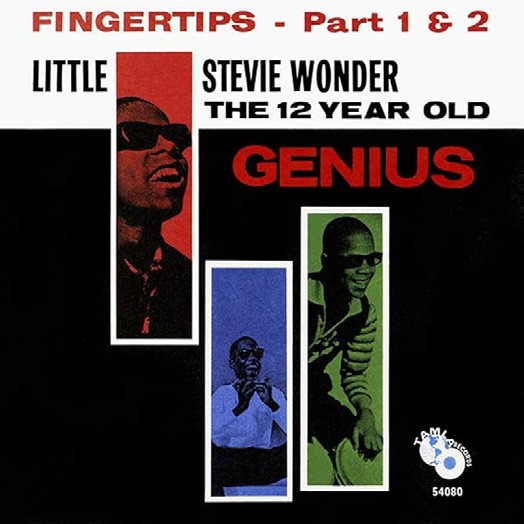

Give the drummer some:

‘Little’ Steve Wonder, the world at his fingertips.

Jeffrey Mayer/Rock Negatives/MediaPunch/Alamy

Steve Kagan/Getty Images, Getty (2), Shutterstock

STEVIE WONDER was r unning out of time and friends.

Just tur ned 15 in the spring of 1965, it was two years – too long in Motown boss Berr y Gordy ’s eyes – since his only significant hit. None of the label’s premier backroom teams wanted to touch him and there was nothing ready for release. With Mar vin Gaye, The Supremes, Temptations and Four Tops all raising the ante in the charts, the Hitsville machine was no place for a lightweight whose forte was youthful pranks and destr uctive behaviour. “He was bar red from the studio,” noted Andre Williams, who co-produced his earliest recordings, “because he’d go in when nobody was there and mess all the instr uments up.”

Four years previously, Stevland Judkins (AKA Mor ris) had char med Gordy with his talent. He had come to Motown’s attention after Ronnie White, The Miracles’ baritone, had lined up an audition. Judkins was 11, blind (a consequence of his premature birth) and already a multi-instr umentalist (bongos, dr ums, piano and har monica). Gordy passed the prodigy over to producer Clarence Paul, and between them they came up with a stage name, Little Stevie Wonder. There was also the matter of a contract, the standard Motown deal being unsuitable for a minor. Royalties would be held in tr ust until 1971 (when Wonder tur ned 21) and he could sur vive on $2.50 pocket money ever y week. What could possibly go wrong?

“STEVIE WAS BARRED FROM THE STUDIO, BECAUSE HE’D GO IN AND MESS ALL THE INSTRUMENTS UP.”

ANDRE WILLIAMS

His first releases bombed but Gordy believed a live recording might get traction, and sent a mobile unit to Chicago’s Regal Theater in March 1963. What it captured was mayhem, as Wonder’s youthful chutzpah spilled over on-stage. Gordy tried to tidy it up for a 45, Fingertips, Part 1, but when he realised DJs preferred the tumultuous Part 2 – Wonder fools around, exits the stage then unexpectedly returns, catching out the big band behind him – he remixed and recut it, promoting the flip and emphasising bewildered bassist Joe Swif t’s “What key?” cry. Both the single and its parent album, Recorded Live: The 12 Year Old Genius – all 23 minutes of it – hit the summit of the Billboard chart that spring, and Little Stevie was on top of the world.

Now, however, after a run of, at best, mediocre placings, Berr y was prepared to cut him loose. Alone at the company, songwriterproducer Sylvia Moy was prepared to take a chance. “I don’t believe it’s over for him,” she told Mickey Stevenson, the head of A&R. “Let me have Stevie.”

The key, she reasoned, might be staring them in the face; if the choice was between the strength and stability of old-school Motown, of Clarence Paul, Maxine Powell’s deportment classes and the vaudevillian Cholly Atkins’ choreography, or the chaos of Fingertips, Part 2, perhaps Wonder could thrive within the latter. She asked him what he had. Not much, it tur ned out, although he did have a sketch that went: “Baby, ever ything is alright. Uptight.”

“He didn’t have completed songs,” Moy explained, “he was into sound.” But in this case, what a sound. A two-chord mar vel, Uptight (Ever ything’s Alright) grabbed from its first second, as bassist James Jamerson and dr ummer Benny Benjamin locked down an archetypal Motown beat under an endorphine r ush of a horn riff – listeners were bludgeoned by the breathless pride the singer expressed in his well-heeled girlfriend from “the right side of the tracks”.

Wonder sounds like he can’t believe his luck, and aptly so. Uptight was written and recorded in such haste that Moy was feeding Wonder lyrics while he sang – there hadn’t been time to translate them into Braille. This was how Motown operated at its zenith in 1965: a month later, Holland-Dozier-Holland wrote and The Four Tops recorded It’s The Same Old Song in the space of 24 hours.

HOLL AND -DOZIER-HOLL AND may be the greatest of Motown’s creative teams, but the quality of the hits Wonder, Moy and Hank Cosby generated in 1965-69 stands comparison: Uptight was followed by Nothing’s Too Good For My Baby, I Was Made To Love Her, I’m Wondering, Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day, My Cherie Amour and Never Had A Dream Come True. Yet Wonder’s 1960s output is regularly unfairly overlooked in favour of his imperial ’70s. As Moy realised with Fingertips, the ideas that would make Wonder a superstar were already in place; during this second act they would be given space to develop.

Wonder was growing up in public. Blowin’ In The Wind, his debut foray into social comment, concentrated on the melody ’s campfire singalong simplicity, but soon he would disguise much harder images in MOR clothing and sneak them onto AM stations for suburban audiences to hum, taking A Place In The Sun into the Top 10 in 1966, and singing “I’m glad I’m chained to my dreams” on Never Had A Dream Come True three years later.

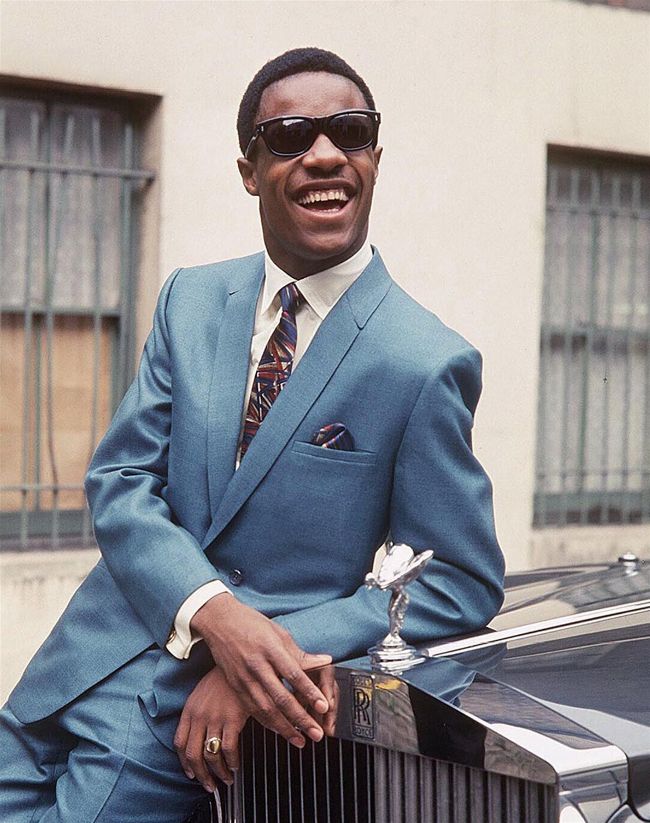

Signed and delivered: Motown’s Rolls-Royce star meets his car equivalent, 1967;

Stevie joins the Motown party, 1964, with Berry Gordy (at piano), Kim Weston (on mike) Smokey Robinson (rear), Iris Gordy (in front of Smokey), Marvelettes Gladys Horton (hidden by Weston), Wanda Young (behind Weston) and Katherine Anderson (next to Iris), and Diana Ross (hidden by Wonder);

Stevie and Syreeta get married, 1970.

If Wonder rarely appears tied to a songwriter ’s intentions – listeners will often get the impression they know the melody more intimately than he does – by late 1966, he was making this a virtue. Hey Love, the closing track on Down To Earth, is the template for the meandering, unfettered vocal style he brought to subsequent albums, the simplicity of the tune subverted to his undisciplined personality. It wasn’t the only one: Don’t Wonder Why (an album track from 1970) would have fit seamlessly on 1980’s Hotter Than July.

While Wonder enjoyed dipping into other writers’ songbooks – even as his own stock rose on that front – no cabaret crooner could sing For Once In My Life with the freedom he brought to it. His reassembling of cover versions peaked on 1967’s I Was Made To Love Her, his hardest album of the era, with ballads nudged aside for upbeat rockers. My Girl, Respect and Baby, Don’t You Do It are commendably ragged, and Can I Get A Witness is turned inside out, with Wonder, band, horns and backing vocalists all seemingly inspired by different ar rangements.

The following year saw Wonder breaking new ground with a Hohner clavinet, the instr ument most closely associated with his 1970s triumphs. Introduced in 1964 and targeted at those hoping to reproduce baroque sounds at home, it would instead find favour among progressive musicians who wanted keyboards that mimicked guitar. It adds colour to For Once In My Life and is the focal point on Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day, its distinctive chords propelling both into the Top 10. Though Wonder was now arguably ahead of Nor man Whitfield’s Temptations in moving Motown into the funk era, even this late in the day albums were the label’s secondar y consideration, with Wonder’s 1968-69 studio releases bulked up with covers of Sunny, The Shadow Of Your Smile and Hello Young Lovers – he’d never shy from schmaltz – and released around live sets replete with show tunes.