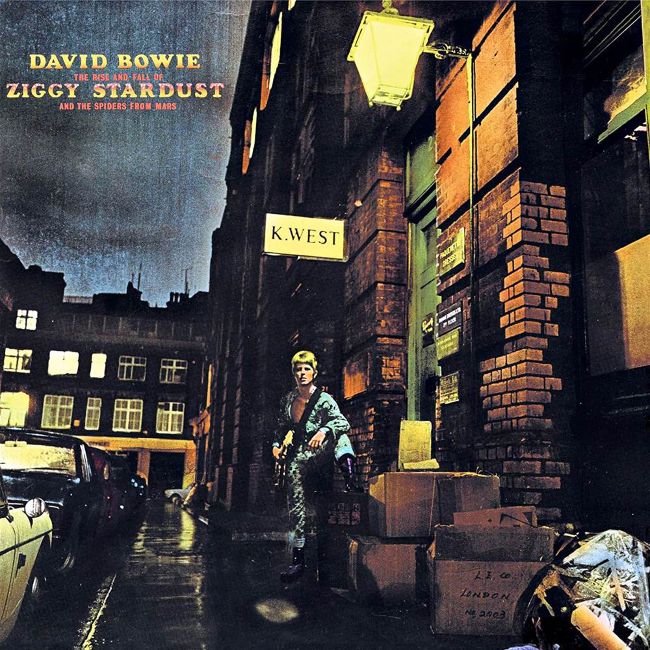

ZIGGY STARDUST 1972-2022

LOVING THE ALLEN

50 YEARS AGO, DAV I D BOWIE RELEASED THE ALBUM THAT CHANGED HIS LIFE AND COUNTLESS OTHERS. A VOLLEY OF FEBRILE SONGS THAT TRASHED THE BOUNDARIES OF ROCK AND POP, A RIOT OF MAD IDEAS AND OUTRAGEOUS GEAR, THE RISE AND FALL OF ZIGGY STARDUST AND THE SPIDERS FROM MARS INVENTED A NEW KIND OF ROCK STAR – MAYBE, FOR SOME, AN ENTIRELY NEW WAY OF BEING. OVER 16 PAGES, BOWIE’S CLOSEST COLLABORATORS TELL MOJO ALL: “ZIGGY HAD TO BE SELF-CONFIDENT, STRANGE, UNUSUAL, DIFFERENT, ALIEN AND VERY TALENTED…”

PORTRAIT BY BRIAN WARD.

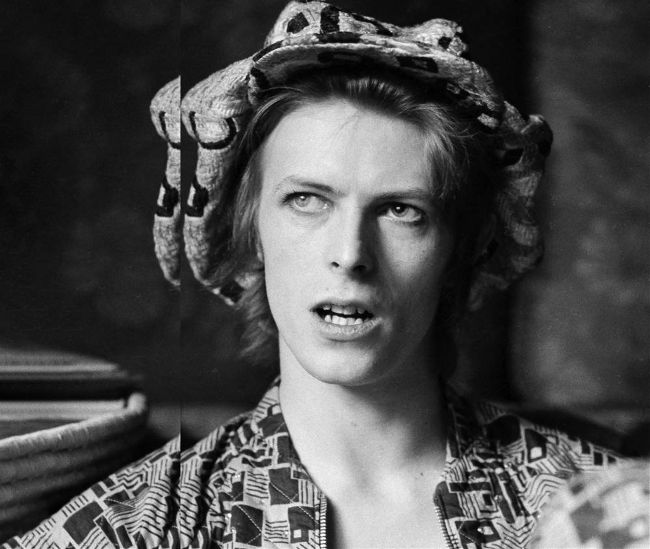

Screwed-up eyes and screwed-down hairdo:

Ziggy moves in for his close-up, 1972.

STAR TURNS

KEN SCOTT BOWIE LEARNS TO ROCK WOODY WOODMANSEY THE BAND FROM MARS MIKE GARSON AMERICA ❤ ZIGGY ANGIE BOWIE THE LIBERACE FACTOR KRIS NEEDS KISS OF THE SPIDER MAN AND MUCH MORE…

THE CONCEPTION

“TOTALLY IN VOLV ED, TOTALLY NOT SERIOUS”

OVER 1971, SOMETHING WAS BREWING IN

DAV I D BOWIE’S BRAIN –A HYBRID ROCK’N’ROLL WHERE SEX AND SCI-FI MET. BY MARK PAYTRESS.

EARLY AUGUST 1971: BOWIE WAS FEELING “A LOT lighter”, he told NME’s James Johnson. Hunky dor y, in fact, the title of the album he’d just finished recording “It’s been gloriously easy to record,” Bowie added, his best album yet. It needed to be. His first three had all been failures.

Hunky Dory was ever ything Tony Defries, Bowie’s ambitious manager since spring 1970, had been waiting for. At Defries’s prompting, Bowie had signed a publishing deal that October, bought himself a piano and set about fixing what he called his “melody problem”.

Changes, Oh! You Pretty Things and Life On Mars?, each sounding like a contemporar y standard, dominated the early part of the record. Deeper into the album, cuts like Eight Line Poem, Song For Bob Dylan and Biff Rose’s Fill Your Heart were geared towards the US market. Perhaps not coincidentally, Bowie’s fellow Tin Pan Alley grafter Elton John had recently broken big in the States.

Mid-month, while NME readers were learning of Bowie’s new “totally involved, totally not serious” philosophy, Defries was in New York persuading RCA Records that David Bowie was a future Elvis – still the label’s crown jewel – rather than a second Elton. Shaking hands on a three-album deal, Defries returned to London and told Bowie he’d secured his future.

In early September, in New York to meet his new backers, Bowie was introduced to Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. He’d been covering Reed’s Velvet Underground songs since 1967.

Errant Stooges frontman Iggy was a more recent discover y. Finding common ground with urban USA’s premier outré anti-stars had a profound effect on him. At Bowie’s suggestion, plans were hatched to bring both over to Britain in the new year.

Fired up by his brush with kindred spirits, Bowie returned to London convinced that Hunky Dory – still three months away from release – was already old hat. Seeing his old mate Marc Bolan fronting a four-piece rock band and transforming British pop with effortless-sounding pop hits, while creating headlines with his enchanted persona, further encouraged him to accelerate.

“BOWIE HAD NEVER SUNG WITH SUCH ELASTICATED VENOM, NOR TO SUCH A SCREECHING, ELECTRIC BACKING.”

The intention behind Hunky Dory had been to spotlight Bowie’s songwriting gifts and transatlantic appeal. That would still serve a purpose. But Bowie’s MO had rarely been to take the systematic approach. Between intermittent gigs, mostly playing as a duo with guitarist Mick Ronson, Bowie booked 10 days in a cheap rehearsal studio in October with drummer Woody Woodmansey and new recruit bassist Trevor Bolder, who’d been on board since early June. This time Bowie envisaged a much rawer band sound.

The template was already there on Hunky Dory. Queen Bitch, the climactic performance before The Bewlay Brothers’ comedown, was the sound of Bowie and his fledgling Spiders From Mars unzipping themselves for action. “Oh yeah!”, Bowie starts provocatively over the song’s sashaying three-chord-trick, a handsome conflation of Eddie Cochran and Lou Reed. It’s tempting to hear in the rising hysteria of Bowie’s “It could have been me” refrain his frustration in seeing his arguably lessertalented peers pip him to the big time. Bowie had never sung with such elasticated venom, nor to such a screeching, electric backing before. But behind the scenes, under cover of anonymity, he’d been flirting with a more flamboyant style for months.

Getty, Mick Rock (2)

It could be me: Bowie prepares to launch Ziggy, 1972; (below, from top) inspirations:

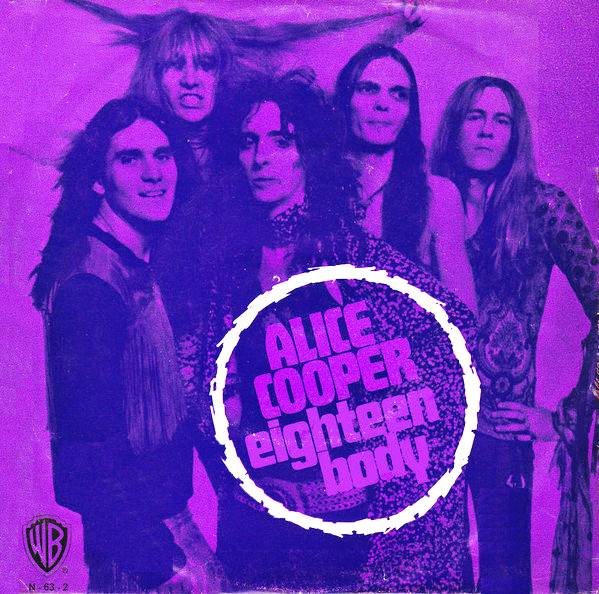

Alice Cooper’s Eighteen, Susan Sontag’s Notes On ‘Camp’ essay, with Freddie Burretti on the cover of Curious, 1970.

THE CATALYST HAD BEEN AN EARLIER VISIT TO the States, for three weeks during Januar y/Februar y 1971. There to promote The Man Who Sold The World, Bowie, a keen student of all things American, soaked ever ything up – the crass commercialism, the whiff of danger, the neon-lit urgency of ever ything. He saw the Lou Reed-less Velvet Underground in New York and heard his first Stooges record in San Francisco. He also witnessed the transformation of Alice Cooper from underground duds into all-American shock-rockers thanks to some B-movie theatrics and a chart-bound teen anthem called I’m Eighteen.

Bowie returned home with a few Legendar y Stardust Cowboy 45s and at least two new songs of his own. Hang On To Yourself was inspired by the Velvets’ pacy set opener, We’re Gonna Have A Real Good Time Together. Moonage Daydream was a slightly wooden piano-style rocker saved by an oddly strangulated vocal.

Neither were considered fit for Hunky Dory. That’s because Bowie had a better idea. While in the States, he’d told Rolling Stone writer John Mendelsohn of his ambition to lampoon the pop business with what he called ‘Pantomime Rock’. He was arguing for a new aesthetic along the lines of that outlined in Susan Sontag’s essay Notes On ‘Camp’, where sincerity is not enough; worse still, it is unmasked as “simple philistinism, intellectual narrowness”.

A week after his return, Bowie demoed both songs with local pick-up band Rungk, giving the project a suitably corny name: Arnold Corns. Considering Bowie’s recent piano compositions, and given his admiration for Andy Warhol’s mentoring ways, Arnold Corns was a convenient vehicle to test-drive a new musical initiative while at the same time flex his latent impresario muscles. Bowie even found a star face to front the project, clothes designer Freddie Burretti, alias ‘Rudi Valentino’. Bowie predicted he’d become a Mick Jagger for the 1970s.

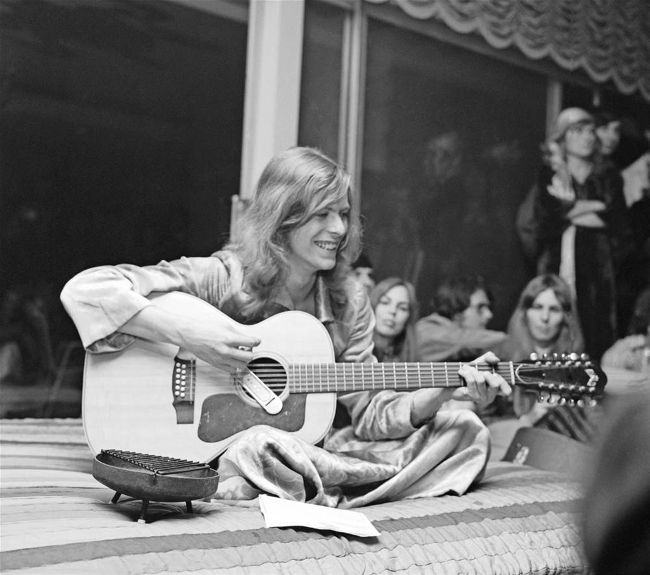

“Have you heard this one?”: Bowie entertains in LA, January 1971; (below) turning red, Haddon Hall, Beckenham, 1972.

Famously, Freddie couldn’t sing a note. Besides, Bowie was far more excited by his new backing band. After a second Corns session in June, with Bowie’s band now providing the backing, he dropped the project. But he’d not forget the songs. During an intense week of Ziggy sessions between November 8-15, Bowie resurrected both. He no longer felt any need to maintain a distance from this more avowedly rock material, nor remain anonymous behind an alter-ego. For this new project, David Bowie would present Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars.

The night before the first session, Bowie took the band to see Alice Cooper at the Rainbow. He was appalled by the vaudevillian spectacle and walked out before the end. Bowie had big ideas for the Ziggy project and threw ever ything at it, from his love of Edith Piaf and Judy Garland (he wanted to be “an entertainer in the old-fashioned sense of the word,” he’d told Johnson back in August) to his desire to create something as impactful on rock as Sgt. Pepper or Tommy. He knew the timing was right, that his ever-growing entourage believed in his talent and above all that his material would stick.

While it’s been said that Bowie was kicking the germ of the Ziggy idea around the States in Februar y 1971, the project unfolded piecemeal. The truth is that Bowie recorded much of the album with his long, blond Veronica Lake locks intact; that the album was still being called Round And Round weeks after the main sessions had finished; that such a quintessentially Ziggy-style song Sweet Head never made the final cut; and that three of the album’s key titles – Starman, Suffragette City and grand finale Rock’n’Roll Suicide – were recorded almost as an afterthought.

With Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie realised his ambition to create a rock’n’roll musical of sorts. The man who’d described himself as ‘The Actor’ on the Hunky Dory sleeve also saw the venture as a way of unifying his shadow career as a mime, an aspiring writer of musicals, even to reconcile his pet subject – the divided self. He also likely intended to leave the mask on-stage at the end of each performance. It didn’t quite work out like that.

THE PREQUEL

AN EARLIER BOWIE INVENTION CONJURES SHADES OF ZIGGY, REPORTS MARTIN ASTON.

ERNIE JOHNSON: an earthbound name if ever there was. Yet the musical that David Bowie demoed in 1968 is the most tantalising of his remaining buried treasures, and suggests early stirrings of Ziggy Stardust.

Ernie Johnson came to light in Bowie manager Ken Pitt’s memoir The Pitt Report, published in 1985, but only when the internet spread news of a tape bearing eight (some reports say 10) songs being auctioned at Christie’s in 1996 did the story truly emerge, as Pitt writes, of “Ernie’s suicide party, described by Tiny Tim, one of the guests, as a ‘Most exquisite party, darlings. Everyone was there. They busted me for masquerading as a man.

How

dare

they?’”

The minutiae of the plot – including a conversation (unfortunately un-PC) with a tramp and a trip to Carnaby Street to buy a tie – is by-the-by; it’s the references to ambisexuality, masquerade and self-destruction, unified by a stage concept, that Bowie kept in his locker for future recycling. And like the

Ziggy Stardust

album, Ernie Johnson lacked a cohesive plot. It seems that the suicide never even takes place. In other words, we’re left guessing.